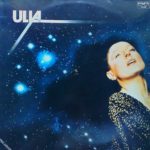

Someone, somewhere, (maybe a massive Polish Jazz aficionado), is absolutely, positively going to hate me for doing this: but I have to profess/confess my absolute love for Urszula Dudziak’s Ulla. Riding that same copacetic wavelength as Maki Asakawa’s Nothing At All To Lose, Urszula Dudziak’s Ulla transformed someone known as the Yoko Ono, Linda Sharrock, or Bobby McFerrin of Polish Jazz into something/someone, in many ways, unfamiliar but in many ways infinitely more palpable. I could talk about the absolute brilliance of her earlier releases like her self-titled debut, Midnight Rain, and Future Talk — works that span the gamut of leftfield soul music, free jazz, and experimental electro-acoustic vocal voice modulation suites — but I’ll leave someone else to do that (check the links embedded above, if you so desire). No, today, what I’m talking about is an absolute barn burner of an album, when Urszula used her unheard of 5-octave (and plus!) range and intricate scat technique to create a whole collection of music you can dance, sweat, and make love to. Here, is where we can call her Ulla.

Who was Ulla? Urszula Bogumiła Dudziak was Ulla, for just a moment. Years before she had been known as Poland’s pre-eminent female jazz vocalist. Under the tutelage of her husband Michał Urbaniak, Urszula began her journey fronting his groups (all self-referential) like Michał Urbaniak Constellation, Urbaniak’s Orquestra, Michał Urbaniak’s Fusion, as lead singer twisting her impressive range almost to function as de facto lead trumpet or saxophonist.

Who was Ulla? Urszula Bogumiła Dudziak was Ulla, for just a moment. Years before she had been known as Poland’s pre-eminent female jazz vocalist. Under the tutelage of her husband Michał Urbaniak, Urszula began her journey fronting his groups (all self-referential) like Michał Urbaniak Constellation, Urbaniak’s Orquestra, Michał Urbaniak’s Fusion, as lead singer twisting her impressive range almost to function as de facto lead trumpet or saxophonist.

That signature scat vocalization Urszula sang with, originally, did not come from choice but due to lack of enunciation. Raised in the small village of Straconka, singing along to the Ella Fitzgerald records she used to love, her native, Polish language, impeded her from ever quite singing the words her idol Ella Fitzgerald would. Turning that impediment into a strength, Urszula discovered “scatting”, allowing her to vocalize verbally and experiment wildly, in ways untethered to language. With her husband, Urszula had gone even further. Urszula used all sorts of gadgetry (synths, ring modulators, harmonizers and vocoders) to fully extend the reach of her range not just tonally but sonically. All those prior albums I won’t go into, deservedly show you how far she could take her voice to function more than just a gimmick.

Let’s pluck a song out of that canon and place it in today’s album, as we’ll do with “Papaya”, as Urszula did on Ulla. “Papaya” originally released on her self-titled debut, in 1975, became an instant success in places far from Poland, in locales mostly centered in Latin America. One can imagine, that she, a rarity, a Polish singer signed by an American label, was intended by that same label to serve as a contemporary Yma Sumac — a technically gifted singer perfectly suited to exploit as some “exotic” tropical music diva.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmxBgHwm8ow

However, Urszula, to her credit, never abandoned her principles and continued her own explorations even on a major label. And for those tuning in for more knotty, scat wah-wah funk, they’d be pleasantly/unpleasantly surprised to encounter songs like “Mosquito Dream” and “Zavinul” which throw you right into a foreign territory where her own jazz explorations find her toying with vocal tape experiments and ambient modal jazz more appropriate for the best stuff on the ECM label. Exotica, this surely wasn’t.

By the late ‘70s it seemed as though Arista couldn’t handle anymore of Urszula’s exploits. Scrapped from Arista’s roster, she resigned herself to help her husband out. At that time, Michał Urbaniak had been one of the few (if not the only) Polish musician to ever be signed by Motown, a step up from the American urban jazz label Inner City Records. Whether by osmosis or symbiosis, Urszula grew into developing a taste for and inclination to experiment with urban music (as heard on the streets of America) and helped pen some of that album’s most wistful tracks.

Unfortunately, for her, Urszula couldn’t find any takers in America that would allow her create and release a new record in the style of contemporary urban radio she had grown to love. All the way in the Netherlands, Pop-Eye Records would sign her on the idea that’d she release a few covers interspersed with originals to actually market her as a new artist altogether. One untethered by her Jazz history.

Released under the name Ulla, Ulla itself was recorded at Electric Lady Studios, in their home base of NYC with a bevy of brilliant funk and reggae session masters backing up Urszula and Michał’s all-encompassing soul vision. Here’s where we can say hello to a few cats that really lent their edge to the atmospheric soul and post-disco you’ll here: on drums (a couple of years away from his work with Marcus Miller) was Omar Hakim, on bass (a year away from tearing it up in the Weather Report) was Victor Bailey, on guitar (fresh from Changes post-disco masterpiece Miracles) was Doc Powell, add to that list Barry Eastmond (also from Changes) on keys, on piano (fresh from his fascinating work with Japan’s Pecker, Grace Jones’ Nightclubbing, and Black Uhuru’s Red) was the incomparable Mikey Chung, additional props go to some Dutch reed players and Michał on lyricon wind synthesizer…but last and certainly not least is Urszula on vocals.

Would Urszula ever sound as free and sensual as she would in “Wonderlove”? Would the Beatles ever sound as bananas funky as they would in the boogie-rework of “Eleanor Rigby”? “Papaya” gets an electro-funk treatment that’s just missing a Cameo cameo — better yet — it’s just missing Maurice White sauntering in with those Earth, Wind and Fire cats to transform it into an even bigger dime piece. Ulla, quite simply, cooks.

“Space Lady”, one of the many highlights, treats West Coast funk as a playground for all sorts of sensitive musical journeys. If Urszula’s voice is her trumpet, on that sleeper of a monster space disco track, surely it sounds like Chet Baker’s latter-day tonalities — to call it warm, would be understating it. It’s of that same star stuff making up Patrick Adams’ best floating post-disco meanderings as Cloud One. In the end, one might be wont to miss Urszula’s experimental flights, but baby this album can be pardoned since it’s all about us. No one has time for that, when it’s time get down. When the album ends on Quiet Storm canon that never was, on “Too Many Nights”, one realizes that this album perfectly played to Urszula’s strengths, it’s what makes it stick with you far longer. Far too many nights are spent worrying, needlessly, about that other shit.

In the end, you had me cuckoo at wordless coo, Ulla.

One response

Dear find sound, still I find myself wondering how she would sound with actual words. I got a glimpse here and there. I wonder if her intention was to capture a feeling, rather than a message.