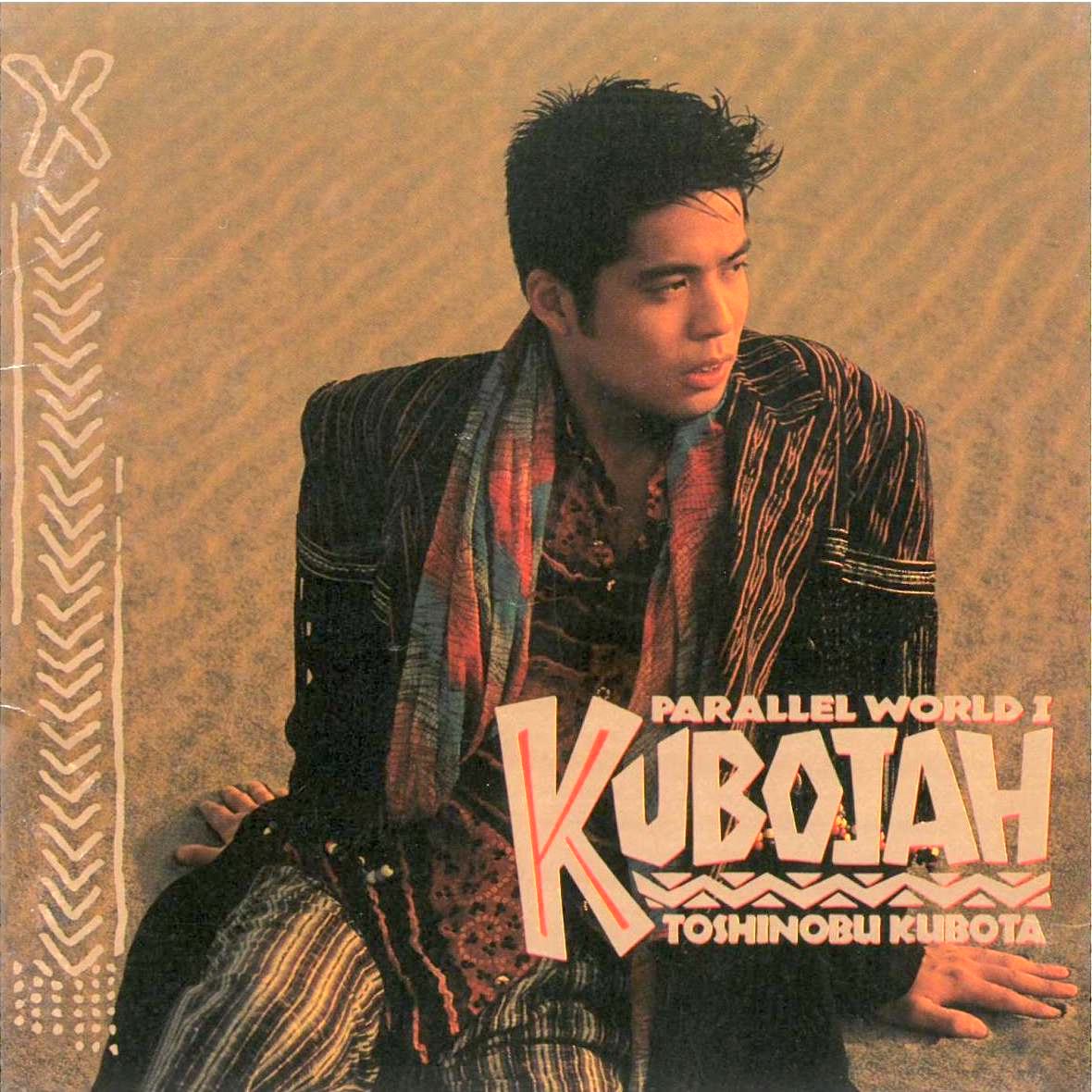

You know, sometimes the hardest part is making a decision. And in my case, it’s selecting the crown jewel amongst so many diamonds. But the choice has been made. The choice is Toshinobu Kubota’s absolutely personal heartfelt ode to the Caribbean and its diaspora: Kubojah – Parallel World I.

The first thing you realize when you start exploring Toshinobu Kubota’s world is just how much it parallels the trajectory of his musical idol, Stevie Wonder. Before he became this giant of Japanese soul music, much like Stevie, Toshinobu came from from nowhere, from Kanbara, Shizuoka, a pretty hardscrabble port city more known for being the coastal gateway to Mt. Fuji than anything of note. It was back then that some of Toshinobu’s earliest memories involved helping run his father’s fruit and vegetable stand and playing baseball in his free time.

In the beginning, Toshinobu envisioned a different path toward stardom. It was baseball where he saw himself becoming a hero. When Toshinobu’s short stature found him frequently passed over every team he tried out for, he took toward his other passion: music.

Toshinobu related elsewhere that his deep love for American black R&B music developed by tirelessly listening to albums by Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Donny Hathaway, and Earth, Wind & Fire during this time. Little by little, it was singing along to this, his favorite music, that Toshinobu self-taught himself English as a language and gathered the courage to become a performer. By the time he graduated from high school and headed to university it spurred him to gave it a try as a lead singer, joining various rock bands (inspired by the work of one Kenji Sawada), eventually leading to winning various singing contests that allowed him to get his first entry into the music business, not as a singer but as a songwriter.

It would be in university, though, where he became absorbed with the much wider African world culture. Somewhere, when he left his small town for Tokyo’s Komazawa University to study Economics, he joined its African Study Group and wrote his graduate thesis on “African music”. What was once a deep love for a small part of the black music tradition grew to a much larger appreciation for all its global roots. Back then Toshinobu stood out by being that Japanese kid who would change his hair into an “Afro” or other historically-black hairstyles.

It was in the early ‘80s, for the span of four years, that Toshinobu did the hard work of earning a living, writing countless songs for singers like Hiromi Iwasaki, Toshihiko Tahara, and Anri, biding his time before someone would give him his first break as an artist. That journey wouldn’t end until 1986, when CBS/Sony offered him the opportunity, looking to see if Japan was ready for a different kind of artist.

For anyone who’s dug deep into the crates for Japanese music from the ‘70s and ‘80s, one can distinctly see that although many artists might have a certain degree of funk and soul influence, it’s rare to think of a Japanese artist that one can distinctly identify as a R&B singer. Of course, there are outliers like Tats Yamushita or Yasuko Agawa, but even they had music couched on strains of jazz, rock, and pop. To outwardly identify yourself as an urban soul singer, one distinctly American-influenced, that was new territory Toshinobu was staking his brand for CBS/Sony to explore.

Toshinobu’s first release, 1986’s Shake It Paradise, as great as it was, presented a tentative but aspirational debut. In it, you hear Toshinobu try his hand out at Prince-style Minneapolis-funk, smooth, Tats-style boogie (as in the brilliant titular track), and gorgeous Philly soul-style balladry as in its “Dedicate (To M.E.)”. However, whether the rest of the album navigated out to where Toshinobu wanted to creatively be, there’s an argument to be made it didn’t.

1987’s Groovin’ began to mark a turning point in Toshinobu Kubota’s career. For this record, he’d take the reins, not as producer, but as songwriter and musical architect composing the vast majority of it. Songs like “Psychic Beat” and “北風と太陽” display a harder-nosed, vastly more groove-oriented direction that far more suited where Toshinobu wanted to be as an artist. Likewise, songs like “Randy Candy” and “Love Machine” presented a sexier, more risque soul sound that was rare to hear from a Japanese singer from that era. Even the remaining trade-offs, smoother songs like “永遠の翼” sound far more strident, as if Toshinobu was truly finding his voice.

What can be said about 1988’s Such A Funky Thang!? For many, rightfully so, this has to be their introduction to Toshinobu. Looking back, its strengths are undeniable. Moved by America’s New Jack Swing scene and influenced by a resurgence in G-Funk inspiration, Toshinobu openly embraced the forward-thinking R&B that wanted to separate itself from the ‘80s. Its opener, “Dance If You Want It” is a pitch-perfect creation showing just what Toshinobu was capable of doing.

Whatever was in the water, if Toshinobu could share it, we’d be that much better, as his stage persona and personality became something else. From choreography to fashion, from music videos to live tours, everything from this era felt like a progeny of the new decade. It’s something you can distinctly see in that hit single’s video, Toshinobu saw larger, global aspirations for himself just in the distance. Just a year later in 1989, his first compilation, The Baddest, rocketed to the top of the chart going on to sell over a million copies. Toshinobu, for all intents and purposes, was the baddest you-know-who in Japan.

All of this makes 1990’s Bonga Wonga that much more interesting. At the peak of his popularity at home, Toshinubo kept search, kept challenging himself. Leveraging the clout of his fame, he convinced CBS/Sony to pony up funds and time to let him get closer to the source of his inspiration.

Tired of having to explain his music to more straight-laced Japanese musicians and producers, he set course to the island of New York City where he rounded up a fascinating cast of characters for a looser creative environment. You see, it was in New York, where Toshinobu felt freer to express himself. In the anonymity of the Big Apple, he could reflect on his roots. There he could walk the streets without being mobbed and simply be himself. In studios, no one asked him to produce charts. There people just went with a feeling, an intuition.

Bonga Wonga, that other album I was torn to highlight, expressed his deepest connection to America and its African roots. Working with musicians like Bootsy Collins, Vernon Reid, Da Bubble Gum Brothers, and Billy “Spaceman” Patterson, to name precious few, the sessions yielded Toshinobu’s most leftfield funk experiments, most glowing soulful ballads, and inspiring indescribable triumphs like “MAMA UDONGO~まぶたの中に~” and “Be Wanabee” that belong in some kind of global urban music canon. Finally, Toshinobu had a full vision. And on this record, especially on songs like “夜想” and “Tell me why~この恋の行方~” his creations had a certain something that his inspirations would have swooned over.

Yet, I chose Kubojah – Parallel World I.

Could it be that I admire what Toshinobu accomplished? It was in New York that Toshinobu challenged himself once again. Why can’t Jamaican music exist in his musical vocabulary? Why can’t he keep rolling that stone?

Kubojah – Parallel World I took the ideas of the Jamaican dancehall and applied it to Toshinobu’s music. You hear it in his fascinating versioning of previously released tracks like “Keep on JAMMIN’”, “北風と太陽”, and “You Were Mine”. It took Toshinobu’s commandeering of the producer’s booth to allow him to fuse previously unheard of reggae influences with all that wondrous new urban music he had absorbed.

In a world that we’re unused to hearing reggaeton and all sorts of hybrid Caribbean pop, here was Toshinobu introducing his Japanese audience to something that wouldn’t exist on either island for a damn good while. You hear this on tracks like “雨音” (Sound Of Rain) a track inching closer to the Walearic school of music. Toshinobu’s lilting “Honey B” has all the special details found in the best Caribbean-indebted love songs. Even the slightly embarrassing island ditties like “Love Like A Rastaman” have something intriguing about them.

Could it be that this album just hits differently? I feel that way when I put on a track like “男たちの詩 〜My Yout〜”. When Toshinobu started his journey, a muscular ragga song like this would be the last thing you’d think he’d succeed in pulling off – yet, here we are. Ditto for his transformation of Bill Withers’s “Just The Two Of Us” into his own kind of street soul (with the help/co-sign of Soul II Soul’s Caron Wheeler).

Something about this record just feels round and lived-in. It’s the all-over sound of “TELEPHOTO” and “神なるものと薔薇の刺”. It’s an album you can just leave on and vibe to. It’s because there’s a special through line that connects the fiery “You Were Mine (Kubojan Version)” to the end of this record, “JAMAICA 〜この魂のやすらぎ〜”. One can affect the love of something…but to truly love it..to truly connect with it…one must surrender to it, to create something that is undeniably part of it.

Although brother Toshinobu wasn’t born where his heart lies, who am I to deny his connection to his heartland? All I and I can do is tip our hand in his direction.