‘Tokiko Kato’ – now that’s a name. A giant of Japanese folk music, it was Tokiko who in many ways was at the vanguard, transforming Shōwa era traditional ideas into more nebulous regions throughout her musical career. But what do you say when, supposedly, such an artist ages out of innovating? Do you put their music out to pasture, as a relic of another generation? No, you put on their speakers Tokiko Kato’s Hana and tell them: “age ain’t nothin’ but a number, baby”.

You see, it was nearly 30 years after her 1967 debut, that Tokiko Kato was invited by Sony to France to record a startling different kind of record. Ever the shape-shifter, in the span of three decades, Tokiko Kato gamely tackled every genre you can imagine – folk, rock, enka, country, Kayōkyoku, latin music – going so far as to cover jewels from European chanson, German lieder and classic Americana. Now, she was being asked to work with a Moroccan producer, to tap into world music of a different kind. The question was never whether she could complete her task. The question was whether it would be good enough.

It goes back to the start. Tokiko’s life has always been lived in defiance of those who thought she’d never make it. Even at birth, a certain fight in her always led her to persevere through many things others wouldn’t. In the beginning, it was simply trying to live another day. Born in 1943, in Harbin, in then Manchuria, now Chinese territory, at the height of the worst in the Pacific theater, her first years were spent on her mother’s back living day-to-day in a Soviet concentration camp, trying to escape that misery. By the time they were able to repatriate to Kyoto, Japan, those experiences had instilled in her empathetic feelings for those who felt powerless and injustice to the world.

When Tokiko was young and working her way through Tokyo University, Tokiko took her first steps toward a musical career, turning an early love for singing into an entryway to songwriting, by entering and nearly winning Tokyo’s Japan Amateaur Chanson competition. As she kept entering and actually winning various singing competitions, she’d become involved in Japan’s student protest movement, unafraid to speak out about government abuses. It was at school she befriended and fell in love with the leader of Japan’s student movement, Toshio Fujimoto. In 1972, they’d marry while he was in prison and for the next two years she took maternity leave from her growing musical career to take care of her first child.

In the mid ‘70s Tokiko’s career would exhibit that fire that would help explain her sojourn to France for Hana. Records like 1974’s この世に生まれてきたら and 1976’s 回帰船 saw her shift from merely a topical singer into protest song and more mercurial personal territory. By the time of the birth of her third daughter, in 1980, Tokiko had become a Japanese household name not by singing at audiences but by singing about the audience itself.

While other Japanese folk singers floundered in the “bubble era”, Tokiko made her most audacious transformations yet. Transforming into a master interpreter and working in the more contemporary styles, she found an audience who could stick around with her form of intimate music. Sophisticated music that ventured into the realm of jazz and European chanson could be heard on albums like 1983’s A Siren Dream (夢の人魚) or Miłości Wszystko Wybaczy, both records that featured heavies like Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yasuaki Shimizu, and Akira Sakata. A younger generation understood that Tokiko wasn’t like every other “legacy” act, she had a voice and vision that brought the best out of her collaborators – no matter what musical idea she was experimenting with.

By the time of the turn of the decade, in 1990, Tokiko had reached such a critical height that earning a Medal Of Arts from the French government played as an encore act to her stunning history-breaking act performing at NYC’s Carnegie Hall just two years earlier (the first Japanese singer to do so). It was in America she discovered that she had breast cancer and had a tumor excised, a secret she kept for many years.

If one can picture Tokiko’s 1991 release, Cypango, as an opening act, one can imagine just what kind of promise she saw in spreading her creative wings out in more “foreign” territory. Her brush with mortality spurred her to go further into her music. On Cypango, en hommage to the world touched in some way by France, and to a lot of the wordly chanson songs she grew up listening to, led to brilliant originals like “A Paris Je Suis Revenue”, “Cypango”, and “Elle Vit Sur Un Volcan”, that saw her trademark singing soar over tracks indebted to the music of Africa, the Caribbean, and Indochina, spreading the balladeering influence into far territory. Yet again, here was Tokiko announcing a new rebirth. Yes, her ideas could build bridges there, too.

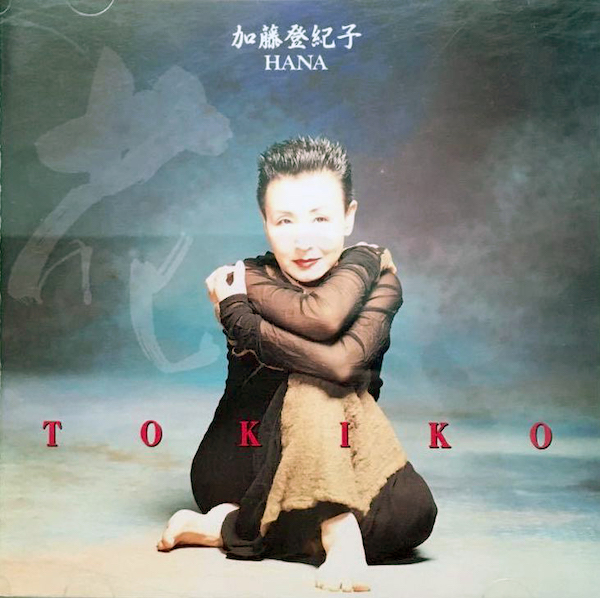

So, in hindsight, as you can imagine, Hana presented another opportunity: a statement piece to a newer generation, seemingly, cowering back into stylistic, genre-based, ghettos. In 1994, Tokiko turned her sights to the indigenous music and people of Japan, that of the Ainu from Hokkaido and of the Ryukyuan in Okinawa.

Using Hana as a platform to reimagine indigenous motifs in fascinating ways, it appeared that Tokiko and Philippe Eidel started to form musical connections between disparate traditions. Songs like “アッチャーメ小(グワ)(Atchame-Guwa)”, for example, took the declaratory style of Ainu folk song and slipstreamed it through contemporary Raï and electronic dance music. That voice which had gained a sheen or two, mutated into a mysterious melismatic creature, sifting through the music.

What can one make about tracks like “シララの歌 (Shilala)” hypnotic songs that sound like they have one foot in the Maghreb and another along the end of the Silk Road? And that the sonic atmosphere is equally as dramatic on songs like “牢屋のならず者 (Nalazumono)”? Once again, genres fail to categorize such music. Tokiko’s vocalese trapezes her roots with roots past many meridians.

At the moment, tracks that speak to me the most are those like “金色の舟 (Kin-Iro-No-Fune)” which invite her French and Afro-French consorts to be unafraid to dig deep into their own well of tradition and join it with her vision of immigrant song. Others like, “3001年へのプレリュード (3001)” rewrite Milva and Astor Piazzolla’s “Rinascerò” in beguiling ways that wring out every bit of Tokiko’s mercurial vocals, making it perfect stage performance material.

Of course, all you need to know about the album is in the music and in the opening track. There you find a meeting of Okinawan tradition with mainland Japanese folk music. I don’t know, at least for me, there’s just something about it, something quite elemental, that feels or sounds like what Tokiko’s always been: someone boldly living in her time, out of time, as a timeless being. I mean isn’t that what makes Hana still capable of speaking to us, how many odd years later? Although, it does make me wonder why Sony won’t let others listen to it, anywhere else…