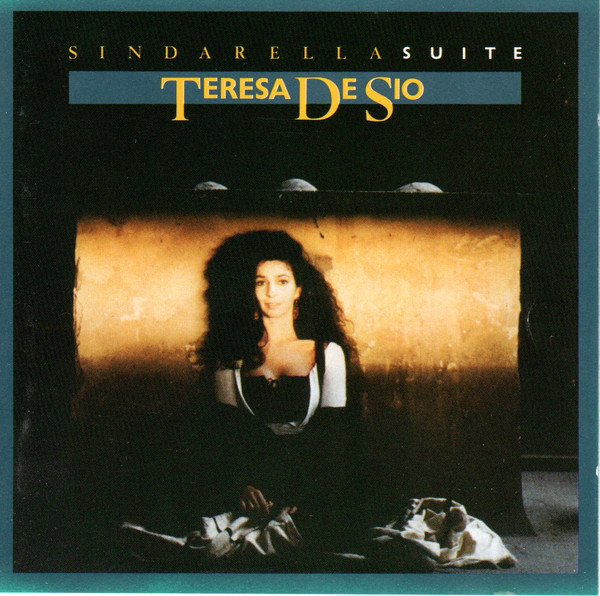

There’s something I really admire about Naples’ own Teresa De Sio’s way of thinking. When I went around digging through interviews to find a little more about the backstory for 1988’s Sinderalla Suite, I encountered Teresa’s fuller story. In it, Teresa painted a much bigger picture than I was expecting.

Drawing out her history — from early beginnings in dance, turning into a singing career (that was started on a lark!), and a singing career that originally steeped itself into Neapolitan folk mutating into explorations of fusion, pop, world music and experimental electronica, all the things she found some kinship in. In bits and pieces I could understand what Brian Eno saw in her to take the time to collaborate twice with such a leftfield Italian pop artist. Neapolitan to her core, Teresa looked at the world outside as a source for influence, constantly trying to find ways to expand on what Neapolitan music truly was.

Franco Battiato, Lucio Battisti or Dalla, Fabrizio De Andre, Pino Daniele, these are a few, if any, of the Italian artists anyone, others can name outside of the homeland. All men and all distinct voices, all seemingly sucking up all the creative critical muscle English-speaking music writers expend on (if they even turn to) Italian music. Forgotten are great female voices like those Gianni Nannini, Loredana Bertè, Mina, to name a few and especially so one Teresa De Sio.

It’s not hard to understand why. Throughout her career, Teresa has been a frequent critic of the conservative Italian music establishment. First came them slagging her for turning back on her Neopolitan folk beginnings. Then came her stardom and the mainstream Italian culture slagging her for remaining loyal to her Neapolitan dialect, refusing (at times) to sing in Italian or to play Sanremo altogether. After a while, she’d ignore everyone and proceed to step outside the continent working with Western musicians in ways that were decidedly influenced by less Western and much less, less European things. Somehow, as her music got more out there what began as a very wild, raw voice, became more refined and smooth, understanding the power of sound judgement.

It was Italian folk giant Eugenio Bennato who originally convinced Teresa to join his pioneering Italian folk-rock group Musicanova when she was more interested in a theatrical career. Unlike the others in that supergroup, Teresa, didn’t come from a folk background her original love was rock and punk music. Her debut, 1978’s Villanelle Popolaresche Del ‘500 largely influenced by Eugenio, was supposed to promote her as a new provincial Neopolitan folk starlet. Within the span of a year she started to chart her own path.

Influenced by the writings of female music critic Maria Laura Giulietti, Teresa tried to expand her musical vocabulary. Enlisting the help of Maria as producer and manager, something frankly unheard of at that time, to explore integrating jazz, funk, and other groove-oriented music into her music, 1980’s Sulla Terra Sulla Luna saw them take Teresa’s sound into uncharted territory. Rather than think of herself as a female singer, she began to think of herself as an artist, solely.

Not quite folk, fusion, or new wave, it was that album that fell more on the Pop side of the equation as it began that not-so-quiet journey to her full potential. Things would truly come into fruition on 1982’s self-titled affair as Teresa would suss out of others just brilliant urban Neopolitan pop music that find alternate angles to Pino Daniele’s western look at their own upbringing, using drum machines and synths to sketch out something unique.

By the time of 1984’s Aumm Aumm, met some guy named Brian Eno her manager invited over to Italy to do a sound installation. With cassette in pocket she urged Eno to take a listen to a demo version of “Tamburo”, hoping to pique his interest in producing her (even if she felt there was literally no chance she’d do either). In style (and perhaps in substance) some saw in Teresa their Italian answer to Kate Bush. Others saw her as the female pop singer that could, finally, stake territory outside of Europe. Somewhere in between lay the true answer, though. “Tamburo” that track that convinced him to work with her showed the potential in their meeting. He was floored by the raw power in that track.

1984’s Aumm Aumm had led Teresa to massive success. Radio hits and TV appearances, where she frequently appeared with her iconic hand drum, had put her at the top of the charts. However, rather than capitalize on this success Teresa jumped at a chance to work with an artist she had quietly admired for a while. Somehow, in between producing U2’s the Unforgettable Fire, John Hassell’s Power Spot and his Thursday Afternoon, Eno took a pay cut, paid for his own stay and way there (and barely asked for a production credit) to somehow bring his own sonic magic to Teresa’s Africana. Teresa herself largely financed this production as her label wanted to distance themselves from what they thought would be alien territory and difficult to promote.

Africana, as implied by the title, was Teresa’s full-throated integration of African music, of experimental electro-acoustics, of things that weren’t superficially belonging to any genre. Recorded in Rome, it predicted fourth world-esque pop in a way, as Ernesto Vitolo, Frank Bruno and Franco Giacoia, augmented Teresa’s idea with electrifying ambient rock that somehow created tracks like “Tamburo” that would become quiet underground dance floor hits. Other songs like “Africana” or “Veneno e Vanno” have that special Italian minimalist sound, see Daniel Bacalov and friends, that Eno’s experiments grazed with Teresa. At the forefront, though, remained Teresa’s increasingly shape-shifting lyricism and phrasing. Africana showed she was not just some Kate Bush-lite but a peer that could command that same bravura.

Two years later, Teresa would come back to what she began there. At that moment she had been working on a mini Italian opera of sorts, Sindarella Suite that simply called for something special. Inspired in a different way by her deep dive into the Italian ballad songbook with Paul Buckmaster on 1986’s classy as hell, Toledo E Regina. Teresa flipped expectations and ventured/veered to the left again.

Teresa, once again, contacted Eno out of the blue, now this commanding producer at the height of his demand/power, and asked him if he’d like to join her again for this one. Surprisingly, again(!), Brian put a lot of somethings on hold and said yes. This time around, though, he’d do one better and ask Teresa if he could invite his friend experimental electronic guitarist Michael Brook and she, herself to record in London, to take advantage of the full appointments of his phalanx of sonic tools.

The first half of Sindarella Suite would be an almost entirely Italian affair as bits and pieces of the larger operatic idea were broken off into songs that became mantras, dances, or experimental bits of electro-acoustic ambiance. “Fatica D’ammore” instantly takes you there with a bit of it all, using a choir backing up Teresa in a way that just floors you with anticipation for what’s next. “Dammi Spago” teases out the last bit of roar for her early fans and then “L’olandese Volante” finds her create that spacious ambient pop warmth that was sorely in dire straits in the late ‘80s.

This double LP finds its true sea legs beginning on “Capinera” featuring Paul Buckmaster’s wonderful progressive arrangements. Here a meeting of the Italian minimalism, world beat, and Procol Harum’s majestic/ornate Grand Hotel somehow exists in these ideas. “Bocca Di Lupo” wouldn’t sound out of place on any largely sample-led art pop we’d hear coming from Peter Gabriel, Laurie Anderson, or Ms. Bush, herself. To exist in that company, though, in this height of their career, is not damning Teresa with faint praise. Somehow, this double-LP never lets up with intriguing ideas that aren’t entirely Neopolitan but endear themselves as not entirely anyone else’s either but Teresa’s. Witness, a positively wicked dance floor workout like “Chi Sta Meglio ‘E Te” which binds largely drum machine-sequenced African pop with bobbles of Mediterranean pop for Teresa to perform some brilliant livewire vocals over.

However, the album’s final turning point begins in the heart beat ambient balladry of “Il Miracolo Di Salvatore Ammare”. Veering from stunningly gorgeous Canzoné to overt light-your-candles-in-the-air pop wizardry, one doesn’t need to know a lick of Italian to sway through all its microscopic twists and turns of emotion. It’s no wonder this became the b-side to “Bocca Di Lupo”’s single. In a just world more ears would have flipped this side as well. Punctuation the finality of the first record to this double LP, “‘A Neve E ‘O Sole” finds Teresa in a nocturnal mood, gracefully putting closure to that side of her as spiraling worlds of sublime neoclassical ambiance swirl around her piano-led torch song.

It goes without saying, with its mammoth, completely side-occupying length, “La Storia Vera Di Lupita Mendera” stands out as this album’s and Teresa’s magnum opus. Recording in around four days, a true anti-war opera, it begins with Teresa stepping back, allowing Liftiba’s Piero Pelù to take the reins in the lead vocal department presenting one startling dark wave of an idea, speak-singing her story, all the while Eno and Michael Brook trade infinite guitar and electronic treatments forming a bed of reflective bubbling under. This intro serves to place us in the story of Lupita a young woman raised in a country dominated by war and violence.

The following section of this suite dubbed “Pulisci I Fucili” brings Teresa into the fold as she half-sings, half-speaks her lines, adopting almost a far more rhythmic delivery to match music building to a metronomic half gurgle, half-sprint tempo, speaking of bread, rifles, blood and creeping dread. “La Battaglia” continues on as the whole crew create a heavier, almost Krautrockian groove to signal the ongoing battle ruining Lupita’s life. “Lupita Nel Bosco” shifts the mood again, it does so by shifting the story to the countryside as a mournful Teresa inparts a few words of loss as Eno comes in with a few glowing piano sounds, barely providing a few glimmers of hope beyond the whole heavy atmosphere. And just as all is lost, on “L’incontro”, Michael Brook’s wandering buzz guitar comes back bringing her back into the land of the living, meeting a deserting, wounded soldier who she falls in love with and imagines a world without war.

The suite ends on Piero Pelù intoning with fervor the beauty of peace meeting Teresa’s acceptance of the overriding strength of love beating back war, all punctuated with Eno meeting all of that with some of the most drop-dead gorgeous synth plucks this side of Ambient 4: On Land, sending the two lovers off into an imperfect world with pitch perfect notes of sonic bliss. As the album ends on a moving tango, on “Guerra Alla Guerra” each sung prayer uttered by Teresa unfurls further and further into a floating world of sonic lift that ends the album on a dance danced perhaps for far too long in our history.

Those who prefer something of substance know that such work of positive movement will always be one that is much harder. But then again, the easier path is to stay in one place letting others dictate your moves. And with Teresa’s life, one can see, that easy paths aren’t the ones with special joys and surprises to enjoy.