“I was born to sing” – so graces the words of Teresa Carpio, to the Japanese-version of her powerful pan-Asian debut, 心己许 (Tokyo Dreaming). And after listening to the record, who am I to disagree? Much like her voice, it was this record that finally expressed fully the range of her voice and her ideas.

Teresa’s story starts in Hong Kong. It was in 1956, in Kowloon, where she was born to a Filipino father working as jazz drummer there and a Chinese mother who was a sometime singer. As stated elsewhere, from the age of six, Teresa was already performing as a singer, entering and winning various singing contests around the country. By the age of 12, Teresa had already left Hong Kong, debuting as a cabaret entertainer in Japan, then dropped out of school and fully dedicated herself to a professional career by the age of 17.

It was in the early ‘70s, when Teresa tried but failed to make a name for herself in the more lucrative Japanese market. By the mid ‘70s, Teresa would head back home and start anew fashioning herself more along the lines of a variety performer, covering famous western soul and AOR hits on Cantonese TV and on records. It was her ability to use her voice to reinterpret the sepia-toned pop and soul hits of the day, that would finally land Teresa her first and truest time in the cultural limelight. Whether on TV or on record, Teresa made it far, breaking into the mainland Chinese musical market, as one of the rare, few artists of Filipino descent to do so then.

For all her success, one thing had eluded Teresa: perhaps, it was a closer tie to her Cantonese audience? For some reason, while singing in English her records sold well…but in Cantonese, she had problems connecting with them. Yet, Teresa tried, in her own way, to reach across the aisle, in spite of some of the soft bigotry that pigeonholed her as some “foreign” singer.

In the span of two records, 1981’s 何必放棄 and 1983’s The Magic Of Teresa Carpio, Teresa chose to sing in Cantonese and to adopt a more “traditional”-minded voice along the lines of then, contemporary Cantopop singers – all to (unfortunately) less and less success. In effect, Teresa could tell something wasn’t working. Those records sold poorly, her concerts were sparsely-attended, leaving her commercially in debt.

By 1985, the aptly titled 何必放棄, saw Teresa forsaking the idea of watering down her music and saw her throwing her lot behind the new crew of contemporary singers looking to shake up their homeland. Featuring songs that took inspiration from electro, hip-hop, and Western urban music, Teresa went so far as self-release, 何必放棄, to escape that pigeonhole she had fallen for.

Even if her record wouldn’t sell, she was now able to parlay her critical revival into an acting career on film and TV. However, that year would not end well. For a time she left for Canada, had her first girl (one future actress, T.V. Carpio) yet everything back in Hong Kong led to the dissolution of her first marriage. In the mid ‘80s, Teresa truly was in some deep funk and had reasons to give up – but didn’t. She had bigger dreams to pursue.

What seemed like many moons ago, at age 14, when Teresa first appeared in Japan, afforded her a different path to take. At that moment, both she and the possible audience weren’t quite ready for her. She’d visit Japan ever-so-often to study the language and imbibe in its culture but she had never thought about it being a new launching point. Now Teresa was dreaming again, perhaps it was there where she could be like one her huge influences, Kyu Sakamoto, and “become a worldwide hit singer”, to do so in a way that was demonstrative of the confidence she had in her singing and who she was a half-Chinese, half-Filipina. Fellow Filipina, Marlene, had shown there was a way.

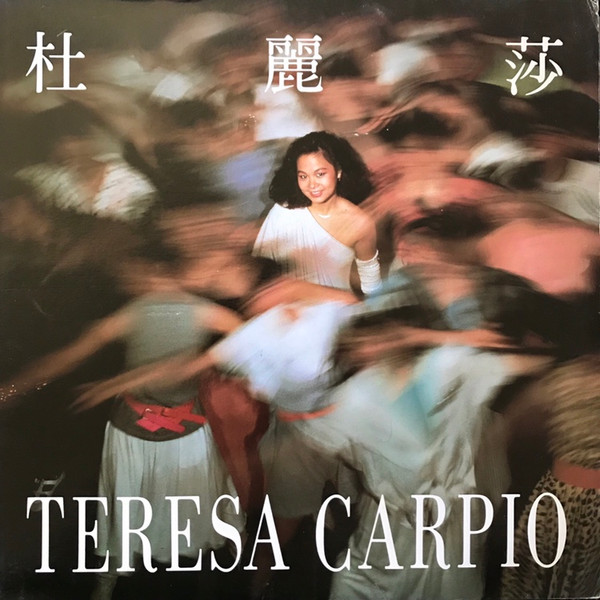

Long-time Japanese composer and producer Katsuhisa Hattori took a chance on Teresa when he invited her to perform in his Ongakubatake Concert in Japan. There Teresa was a hit and proffered herself the opportunity to sign with Warner Bros. Japan. For this record, Teresa chose to record an album not in Japan, not in Japanese, but in both English and Cantonese, with Japanese musicians and production, to marry all her horizon-filling ideas to a new audience she believed might understand her ideas better.

In 1986, Teresa spoke of feeling inspired by the artistry of Diana Ross (whom she was frequently compared to) and Sting, understanding that her taste level needed to ramp up to meet the occasion. The aptly named, Tokyo Dreaming was her attempt to capture a certain zeitgeist of Japanese music.

What I find fascinating about 心己许 (Tokyo Dreaming) is just how Teresa and Takeshi Kobayashi (her main collaborator for this record) shift Teresa’s music towards a more sophisticated, adult direction. If anyone’s listened to Takeshi’s Duality you’d find obvious sonic touchpoints of that touch here in Teresa’s music. You hear it in songs like “心己许 (Heart Already Given)” that mix a certain kind of lovers rock with a special kind of spectral synthpop. Others like “热过之后 (After The Passion)” have that certain je ne sais quoi of Japan’s burgeoning ambient pop scene and Teresa puts her own imprint with a decidedly jazzy bent. It’s all impressive. It’s all far more contemporary-sounding than anything she ever created before.

While in the past Teresa’s glorious vocals were there as a way to interpret classics and standards, on 心己许 (Tokyo Dreaming), Teresa offered a large tranche of originals that were quite vanguardist for her time. I say this, because you’ll gear to hear amazing tracks like “梦到未来 (Dreaming Of The Future)” appear. Track like it or “我痛苦 (I Am Suffering)” taking inspiration from the late, great Ryuichi Sakamoto’s 音楽図鑑 (Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia) through tinges of a certain avant-pop stylings unheard of in her existing music and more in line with what Kate Bush was doing in the West. Others like “爱情监狱 (Prison Of Love)” are made in a Walearic mold, building from the Marina Pop slowly becoming out of fashion in Japan.

For all the smiles you see Teresa with on the album, one read of the track titles – those that speak of “life after marriage”, “farewell sorrow”, and “dreaming of the future” – can lead one to believe that this was a deeply personal record for her, full of airs of her past, present, and future. Yet for all that, somehow, in Japan, all that earnestness turned to hard-earned victories, all hers, fully-earned in a foreign country that welcomed her with open arms. When she returned to Hong Kong, it would be the task of others – perhaps like the great Sandy Lam – to take this spirited time in her life and run with it in the spirit of a “New Asian Music”.