“Prince.” Now with that out of the way, can I focus on what I think is one of J-Soul’s least heralded and easily most slept-on albums: Shinji Harada’s Doing Wonders (ドゥーイング・ワンダース)? Before you think that all this blog likes to share is background music for taking a nap or studying, I’d like to let you know that the albums I look forward to sharing with you the most are those that are full of a different kind of energy. However, like anything, there is a time and a season for all things and thankfully, in this case, a lot of the leg work has been done by others for me. And who isn’t ready for a bit more heat?

Rather than posit you with a quite lengthy backstory about Hiroshima’s Shinji, let’s focus on the specific period of time that led to the creation of Doing Wonders. Arguably, one could say the turning point that transformed Shinji from one time cute, pint-sized J-Idol to something else, an artist (through and through) that’s far more nebulous, began in 1981.

In 1981, at a huge Christmas concert performance, Shinji announced he was suspending his career to live and study music in America. At the height of his popularity with a huge fan clab counting in the multiple thousands, Shinji had enough. In the beginning, his love of Western music had spurred him to pursue a pop sound influenced by the likes of Elton John, Gilbert O’Sullivan, and other MOR musicians, but now at the start of the ‘80s he felt utterly devoid of direction and increasingly the worst of all: dated.

For Shinji, it wasn’t a limitation because of technique, budget, or other thing that brought him to America, it was a need to put himself in a position where he would be able to create something uniquely his. A year or two abroad forced Shinji to realize that Japanese pop music itself, or at least the one he’d like to make, was in a rut. In America, the influence of soul, disco, hip-hop and funk was more palpable. If and when he’d come back to Japan, it would be because he’d want full control of the direction of his music, and all signs pointed to that arrow heading to “dance” music.

It was upon his return in 1983 that Shinji consciously broke away from his idol days and created his own publishing company he’d dub “Crisis Rock Music” to cement ownership of his future music and production. In Japan, he’d take the lessons in groove music he practiced in America to heart and took his first steps into creating the Black American-influenced soul music that was a bit divorced from the smoother, West Coast-influenced “New Music” dominating the Japanese airwaves. His initial release under that influence, 1983’s Save Our Soul, was a gentle nudge signaling to his fans this new direction, away from the rock direction he found success with in Natural High.

A performance announcing his next release, 1984’s Modern Vision, introduced the break away. In the past, he’d use the moniker of his backing band “Crisis” to create albums full of proggy or psychedelic experiments. Now Crisis came back in a supporting role fleshing out the stage show and a concept Shinji was toying with, of modern Japanese soul music at the cutting edge of contemporary urban music. In it you’d hear the influence of the mutant funk of David Bowie and the dark pop of Michael Jackson. With full control, Shinji would write, arrange, produce, and perform all the tracks on the record. Performances of the songs became rip-roaring affairs full of choreography and lengthy stage shows where he’d stretch out album tracks.

While Modern Vision showed Shinji capable of dipping his toes in various pop directions – never mind his dramatic aesthetic change (cutting his hair and wearing makeup) – it also showed that his best ideas laid in the dance cuts heard on it. Songs like “Modern Vision ACT III” and “Let Me Hold You Again Tonight” graced fans with aped styles that unsurprisingly befitted Shinji’s vocal range. If Shinji truly wanted to take the next step he’d had to be willing to go after the top guns of pop.

In the ‘80s, no one artist was as synonymous with bridging the gap between New Wave, urban radio, and rock quite like Prince. Shinji was not immune to this realization. As many before had, he saw in the Great Purple One a north star to follow. After the release of Purple Rain, this idea of having a nightclub where people could go dance and listen to great music would stay in Shinji’s head. Why not create such a space for his Japanese audience?

Shinji’s next release, 1985’s Musical Healing, would be the product of his exploration of marrying the “Minneapolis sound” to a Japanese sensibility. Before its release, Shinji and his band took up residence, setting up a regular “Friday Night Club” where fans could see them appear on stage. Wearing modified traditional Japanese-garments, in even more androgynous-looking style, Shinji would do his best to put on a show, singing, performing, and dancing on stage, urging them to take off and dance with each other. Rather than run away from the sexual connotations of that sound, songs like “Heat Dancing”, “Oriental Kiss”, and “Magical Healing” and “Subway – の夜明け” went all in on the decadent dance style that the Artist would largely abandon after his star-making film and soundtrack.

So, why the focus here on Doing Wonders (ドゥーイング・ワンダース)?

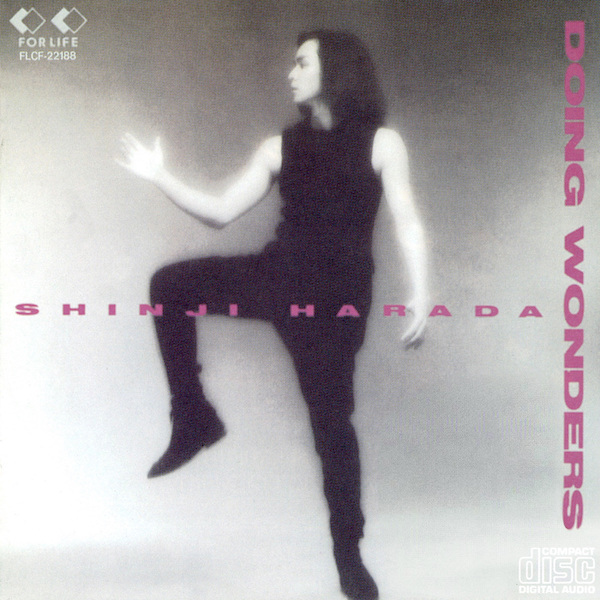

Because Doing Wonders (ドゥーイング・ワンダース), is exactly the point where a protege became the master of his own domain. Once again writing, performing, and producing every track on the album, Shinji took what he learned a year earlier and simply did it with more confidence. Although the single would be the paisley-tinged, “見つめてCarry On”, everyone’s introduction to the record proper, would be the Friday Night Club stage favorite “Sexual Selection.”

Playing like lost, peak-era Prince, what could have been an off-brand, Japanese take on a special Black American sound, featured quality (true quality) that would have made the late, great one blush. Toying with the idea of sexual preference – at a time when Japan was still decidedly conservative about such things – was more than just being provocative.

A track like “Doing Wonders” wouldn’t have its special air, if it didn’t speak to Shinji’s own background (and show it in its sonic palette). Shinji knew he had the music to leverage his powerful messages. Pure musical candy like “夏のDelay” wouldn’t resonate, to this very day, if it didn’t harken back, perfectly, to a certain sound (or era and artist) that left plenty of room in those ideas for others to explore and further evolve.

Doing Wonders (ドゥーイング・ワンダース) had a certain communal spirit (if not only in sound and emotiveness) that still sounds like little else in that era of Japan. There were barn burners like “風をさがした午後” for nonexistent clubs. Albums like these, as you can imagine, that push the envelope would never sell as much as his earlier stuff, but they’d go on to solidify him as the artist he always wanted to be. Japanese aunties and grandmas might still like his older stuff but us younger folk, well, there’s still something there to work from.