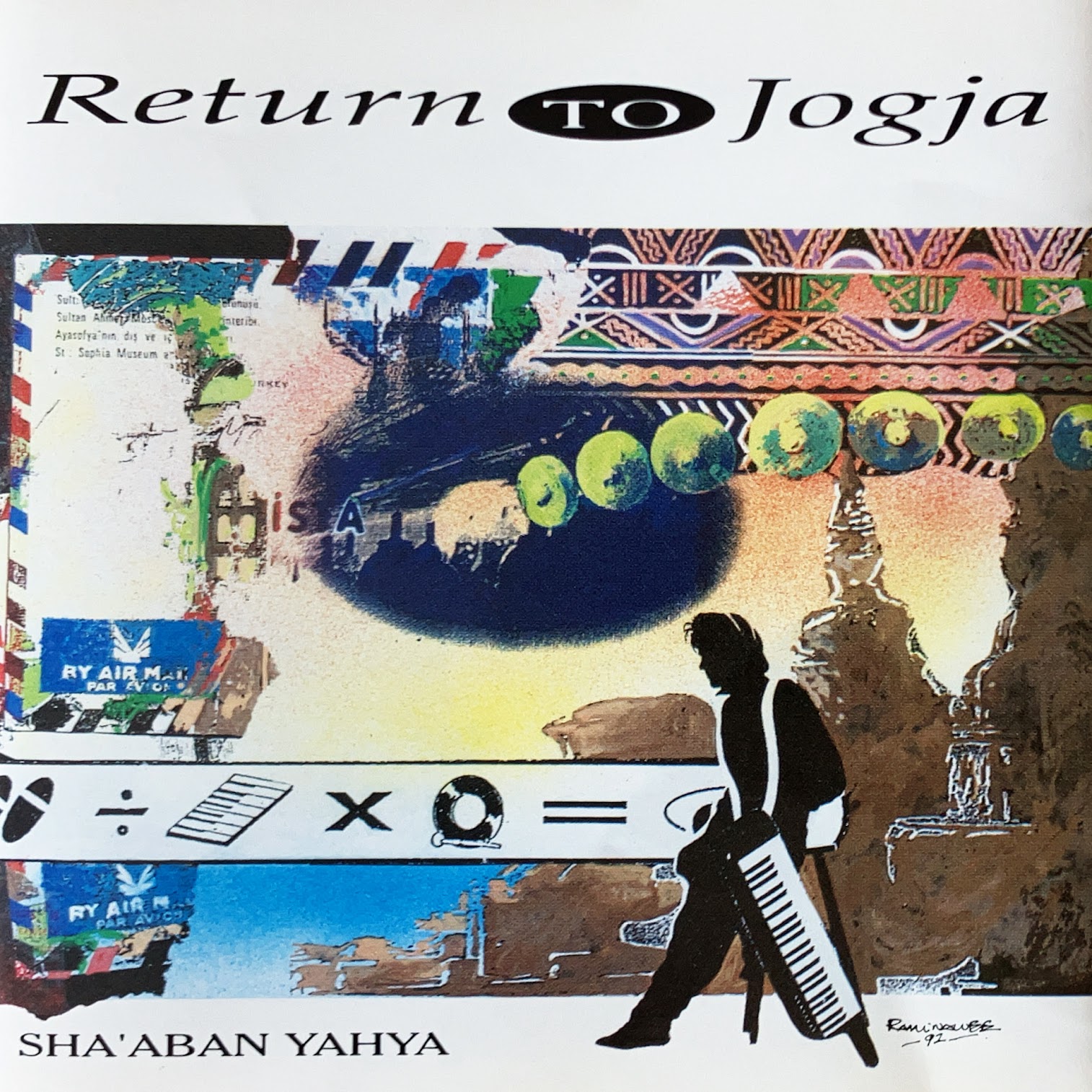

You know, sometimes you’ve got to step back and realize that there’s only so much thread to pull at. It’s not ideal, but it’s something I keep reminding myself of when I have to write about (or share an album) much like Sha’aban Yahya’s Return To Jogja.

In the ‘90s, a pair of Singaporean nationals, George Lim and Kovan Goh, were on the lookout to start a new record label. Inspired by New Age labels like Windham Hill and Celestial Harmonies, they looked within Asia for musicians they could use to build their roster. It was in Indonesia where they met one, Sha’aban Yahya.

Sha’aban had taken the long route to music. His first entry to music was through the gift of trumpet lessons an uncle had gifted him. When he couldn’t afford to keep attending, Sha’aban resorted to teaching himself, learning just enough to get a foot in the door with music instrument companies and transitioning to becoming a keyboard player and session musician.

It would be in the mid ‘80s when Sha’aban working as a keyboard salesperson stumbled into computer music, and set about creating his personal studio at home. Using a computer-based studio allowed Sha’aban to fully explore a break away from genres popular at home, to fully explore imaginative worlds of his own creation.

You could say that Sha’aban was fortunate to have signed on to what became George and Kovan’s Celestial Court record label. From October 1991 to May 1992, they invited Sha’aban to Singapore to compose and record all the music that we’d hear on Return To Jogja.

It was in Singapore where Sha’aban, bolstered by a long list of samplers, synths, drum machines and sequencers went deep into the recesses of his mind to come up with a concept for this album. What he landed on was to create instrumental music touching on a love story of sorts.

In Sha’aban’s mind, on this record, he constructed a story of two people who met, fell in love, departed, and ultimately rejoined in Yogyakarta/Jogja, Indonesia. It was the trappings of a storied romance couched in the mystery and history of the Indonesian environment which triggered moments of yearning, nostalgia to do things differently.

So what one hears in Return To Jogja is some sort of elegy to a rustic Indonesia one can’t truly escape back to. Songs like “The Calling” explore traditional gamelan-driven music and give it airs of secular New Age humanism. “Journey Back To Jogja” presents the first true break from the past, with sampled percussion and wind instruments painting a hypnotic arrangement that recalls Indonesian folklore but also travels elsewhere.

Something that I marvel about Return To Jogja is how certain tracks like “Searching And Yearning” and “Faces Of Jogja” share the esoteric idea of “cosmic music” explored in other places like Germany, famously. It’s not hard to listen to something like the former and think of the worlds created by others like Klaus Schulze. “Faces Of Jogja”, in some parallel world, mines the same hypnotic territory that Manuel Göttsching explored, using dance music as a way to apply a rotoscope on a certain kind of universal saudade. Return To Jogja is a fascinating reframing of an imaginary Indonesia that could exist in the realm of anyone’s creation.

It’s Sha’aban’s spirited musical imagination that drives the circular, hypnotic, rhythmic creations that follow next. You hear it in the glorious polymeter melodies of “Jig Of Joy” wrapping your ears in welcome daylight. Shifting gears, “Living in Jogja” uses carefully placed, muted arpeggios to bring down the tempo into a meditative place perfectly suited to this journeying music. Then the album finally ends, perhaps in meta fashion, with the neo-Javanese stylings of “Myths and Legends”, a dizzying piece that slipstreams the spirit of the past into an unplaceable new harbor.

Believe me, with great pains I’ve tried to reach out to Sha’aban to explain more about his story, and that other story, but I have to assume his quietness leads me to believe he’d rather let the music do the talking (and all that walking).