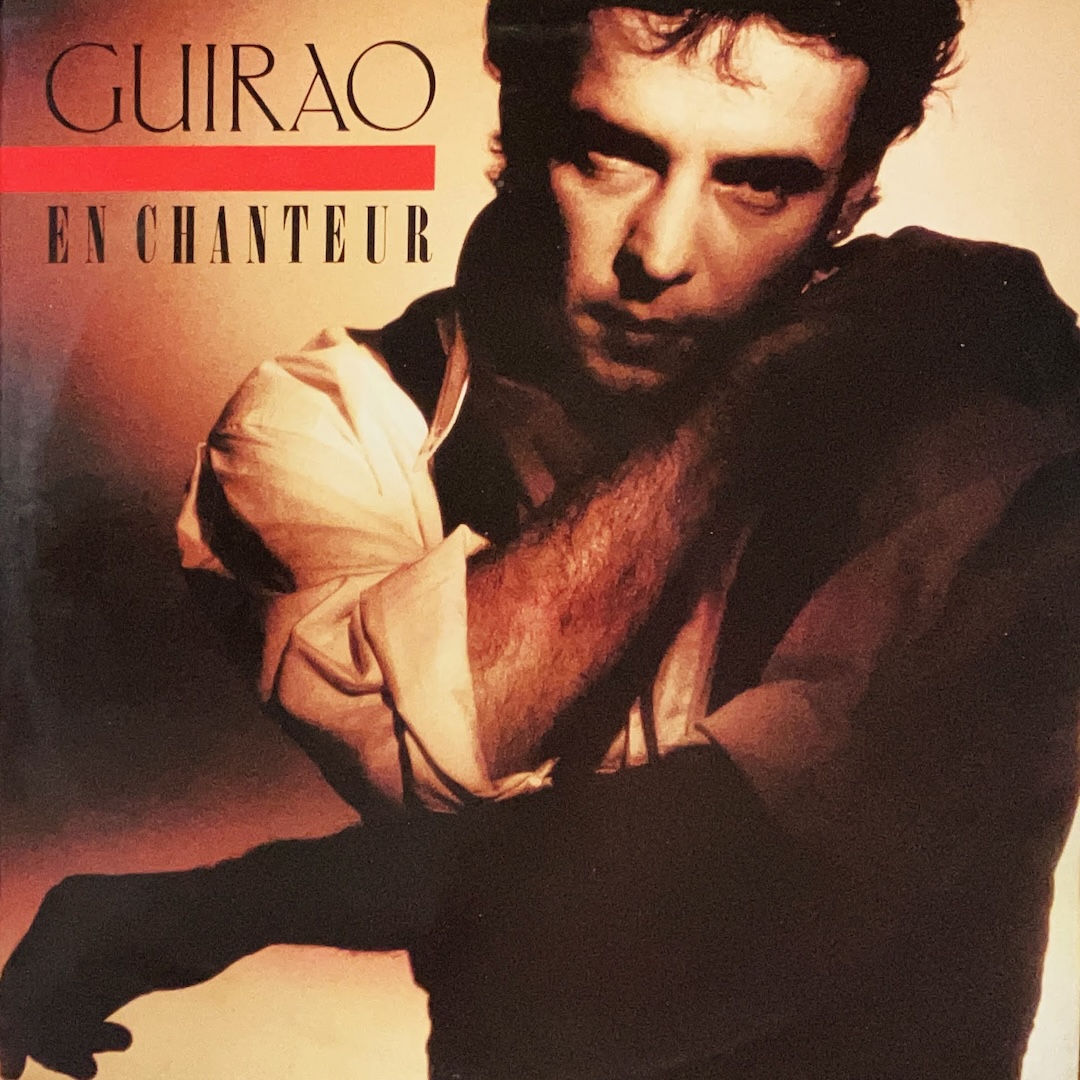

As I write, it sometimes takes me a beat to realize just how connected I am to a person’s story, just as much as I am to their music. Reflecting on the life of the recently departed Serge Guirao, whose long struggle with multiple sclerosis ended in 2021, I’m reminded that for some of us, it’s our roots that never truly leave us—often for better, rather than worse—in everything we do. Serge’s album En Chanteur reminds me of this, in both his music and story: how being an immigrant, feeling displaced, can give us a certain strength, a certain conviction, to build stronger bridges rather than erect useless walls.

Serge’s life didn’t begin in France but in Morocco. Born in 1954 to Spanish refugees fleeing Francisco Franco’s nationalist dictatorship, Sergio Guirao García’s parents tried to eke out a living in North Africa, uncertain if they would ever be able to return to their homeland. It was in Africa that Serge first fell in love with music, hearing a mix of transnational songs—from Portugal, Spain, the Maghreb, and France—blasting from Moroccan radios. Before he had any sense of identity, he understood music in a universal way. You could argue that it was in those tender years that he developed his deep affinity for Mediterranean music.

At age 12, Serge followed his parents to Toulouse in southern France, where they settled among a small but significant expat Spanish community, which had grown after Europe’s post-WWII demographic and political shifts. Like many first-generation immigrants, Serge felt the struggle with Francization. Speaking accented French led to a certain aloofness and shyness that allowed him to blend in without fully feeling like he belonged. That reticence to talk led him to find another way to express himself: through music, where he discovered a truer voice.

After graduating from secondary school, Serge enrolled in the Toulouse Conservatory, where he studied double bass and music theory. In his free time, he performed with various Toulouse-based bands, exploring jazz, rock, and everything in between. Early stints in the city’s myriad recording studios led him to sing backup on records by artists like Jean-Pierre Madère and Émile Wandelmer. Yet, as lucrative as that work could be, Serge quickly realized that if he wanted to create the music he truly desired, he’d have to go solo and strike out on his own. An urge to rediscover his Spanish roots set him on the path to the fascinating music he would eventually make.

In a way, Serge’s return to Spain was a way of connecting with his ancestry in a manner his parents never could. His parents were obsessed with the idea of returning home but, as refugees, were barred from doing so by the Francoist regime. When Serge set foot in Andalusia, he reconnected with his family and Spain’s landscape, observing everything they had all missed with fresh eyes and finally feeling those roots in real life.

At first, Serge tried setting Spanish poems to music, a creative outlet that led him to settle in Madrid and attempt a career as a singer-songwriter. However, for his first six years, Serge had to settle for playing backup—literally—becoming known for his bass and vocal accompaniments for artists like Miguel Bosé. It was another opportunity—to accompany Argentinian singer Alberto Cortez on a tour of Latin America—that proved more creatively fruitful and influential.

For three years, as he traveled across Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Mexico, and more, Serge (by his own admission) discovered a wealth of other traditions—tango, salsa, nueva trova and more—that expanded his understanding of what “música en Español” could be. He realized that no matter what kind of music he created, it had to contain a hint of that Hispanic touch, one resonating closer to his harmonic system.

Back in France, Serge began to explore the duality—or rather, the multidimensionality—of creative, spiritual, and physical influences in his music. He began to think of himself as a Latin singer, first and foremost. An early album, sung entirely in Spanish and produced by Alberto Cortez, was released in 1981 but has since been lost to time, though not to the direction Serge would later take.

His early singles as a singer-songwriter, like 1983’s “Fréquence Passion”, show him experimenting with combining Latin balladry and New Wave. In those early days, a different singer—America’s Gino Vanelli—served as a guiding light, proving that you didn’t have to share the same cultural background to influence a certain style. Yet, as Serge developed his own voice, singles like “Signé Señorita (Envie De Toi…)” showed him moving beyond the traditional sounds of Latin America, retooling their forward-thinking movements into music that looked ahead.

As a singer and songwriter, it was Serge’s next two singles—”Fascinación De Amor” and “María”—that set him apart from his peers and helped establish his unique identity. Working with the equally brilliant François Bréant, they realized that his new music had to embrace everything that made Serge who he was: gentle, soothing, warm, rhythmic, soft, sensitive. The tone and tenor of his sound transformed his Latin influences in a way that broadened their appeal. It’s no surprise that these songs found popularity in Mediterranean cities like Ibiza and Palermo, where he often performed.

“Fascinación De Amor” perfectly captures Serge’s aesthetic. Taking the spirit of Latin music, he distilled it to its minimal essence and ran it through the ghostly presence of electronic machines. As a singer, Serge embraced the weight of its swaying rhythms, molding and contorting his voice with all the drama needed to fill the song’s open spaces. Whether sung in French or Spanish, his “third way” of music presented a singer in tune with a new idea of what the New French singer could be.

In 1988, Serge held recording sessions in Toulouse with François Bréant, Jordi Mora, Laurent Stopnicki, and other elite musicians to craft his vision of a new Mediterranean sound. Gorgeous songs like “Mon Attentat” broke from the typical sonic markers of Latin-infused music, instead using samplers, guitars, and percussion to evoke the spirit of Latinicity filtered through a globalized modernity.

These Balearic songs—including “Devine”, “Copains-Copines”, and “Ça Sera Qua”—had the energy of dance, with layers of technical prowess, ambiance, and sensuality. The music didn’t fit neatly into any one category—it existed in a space between black and white, a place more interesting than either extreme.

Drawing from a suitcase full of influences, Serge crafted atmospheric dance ballads like Devine, presenting the kind of sleek, ethereal sound Bryan Ferry aspired to but could never quite reach. The salsa-meets-ambient sound of “Copains-Copines” radiates starlit warmth, like an irresistible Italian canzone, while the electro-tango of “Ça Sera Qua” reimagines the work of his early influence, Alberto Cortez, in a spirited and uniquely personal way.

“Combat De Cobras”, released as a single from En Chanteur, brought Serge to a larger audience, leading to TV and stage performances that earned him a brief surge in popularity. His minimalist reimagining of Dire Straits-style svelte rock with a samba twist was unheard of at the time. Those who tuned in were captivated by the postmodern dance music Serge had developed for his live shows. Yet, despite his brief success, few knew how to categorize his music, while songs like “Entre Le Ciel Et La Terre” hinted that the dance floor was Serge’s ultimate destination.

With Serge’s passing, friends and colleagues have shared just how singular his voice was in everything he did. Before his death, he could be found at La Mounède translating 11th-century Arab-Andalusian poems into song. In Toulouse, Montpellier, and Angers, hotbeds of French immigration, Serge set Pablo Neruda’s poetry to “French” chanson. Alongside Vicente Pradal and Rubén Velázquez, in southern France, Serge would lend his vocal harmonies to Noche Oscura de San Juan de la Cruz before his illness brought an end to his endless search.

Though Serge Guirao may never have been cut out to be a star, and though time sent his velvet voice in different directions, when his name is uttered by those sadly, increasingly, precious few who remember him, it brings to mind something entirely different from where he began. That’s why I’m here, trying to convey to you just how special this music was when it started—and how it remains even more so now (when he’s no longer around). Between seasons, in the push and pull of hot and cold, there’s “Un Paradis Sur Terre”, a collection of music to travel through. You might even call it “music for open borders.”