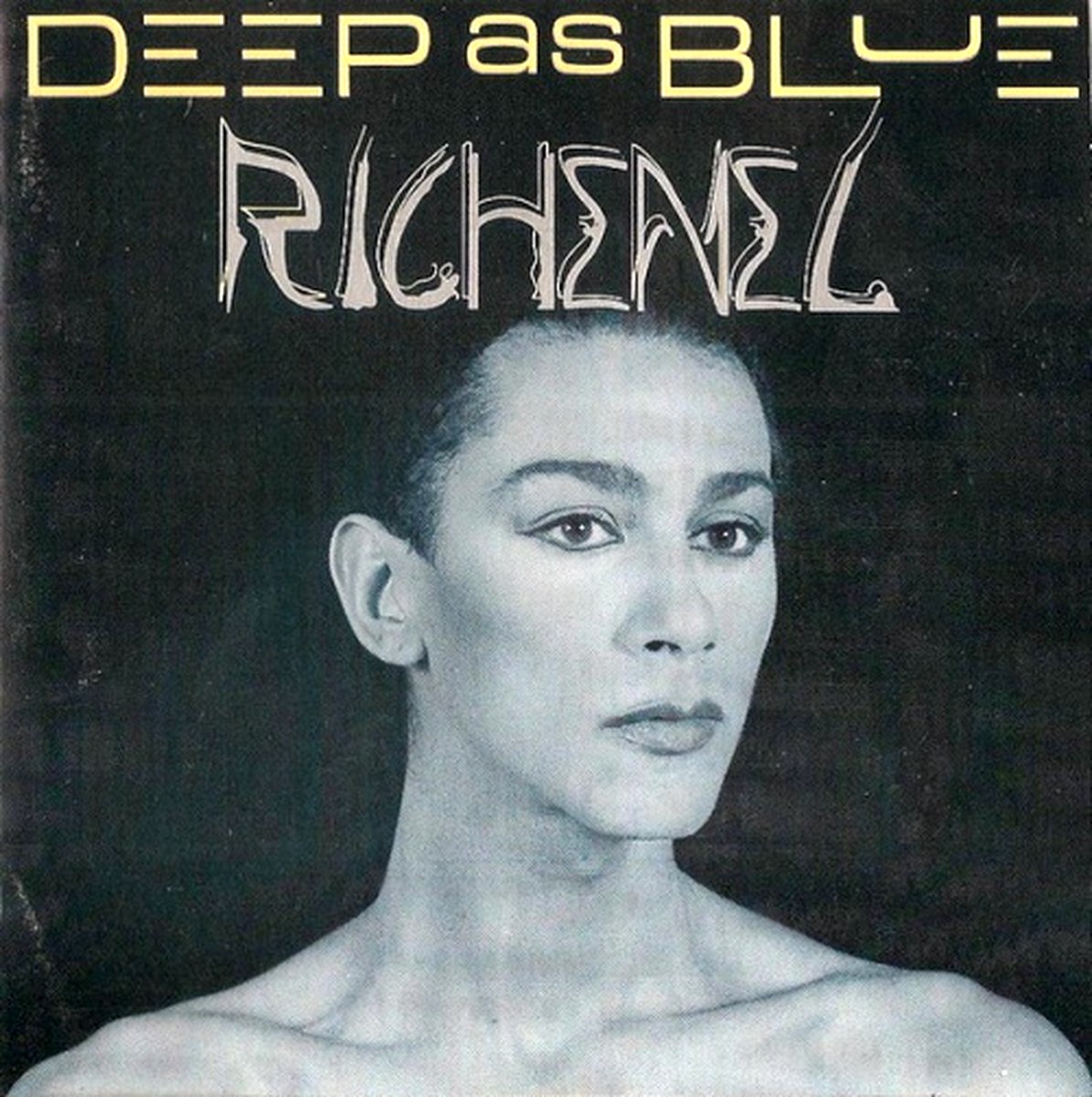

I gotta say: some of my favorite albums are those “imperfect” ones. Although they may not contain a complete record full of highlights, all is forgiven, because of those that do exist in one album. It’s those albums like the late, great, Richenel’s Deep As Blue.

Richenel has the distinction of being as known as he remains unknown. And among those who love sophisticated pop or soul music, all we can remember is his potential. You see, there was a time that from his native Holland, in English clubs and European discos, Richenel was trying to trapeze his way as an “out” pop singer, trying to find space for his kind of music.

Born Hubertus Richenel Baars, in 1957, in Amsterdam to a Surinamese father and Dutch mother, growing up, Richenel was always a deeply creative person (never too far away from a pen or paint brush). His love for music would come from experiencing flamenco performances in Spain – a connection with that country that would later influence his music.

By the time Richenel headed off to university, he had settled on a career in fashion and became active as a singer in Amsterdam’s late disco scene when not working as a model. It was in that early ‘80s Dutch post-disco, post-punk, New Wave scene, that Richenel became known for his operatic voice and his unabashedly androgynous image.

Early ‘80s releases, like La Diferencia, pressed privately or on small Dutch indie labels, expressed an early Richenel who was coming into his own as a gay man and as a musician trying to find a place for his multi-language, cross-genre, vision. In interviews, Richenel would name check artists as disparate like Grace Jones, Talking Heads, and Fad Gadget, as influences. By 1987, the time he’d sign to a major label, on the urging of Dutch producers, Eric van Tijn and Jochem Fluitsma, ethereal songs like “L’Esclave Endormi” (released in 1985) had already featured him working with artists as varied as 4AD’s Ivo Russell and dipping his toes as a smoothed-out, synth-popper on his debut, Statue of Desire.

Although, Richenel, would go on to express a dislike for the music he’d make next, one can’t help but understand why others saw in him a potential star in the making. As a performer, on hit songs like “Dance Around The World”, Richenel tapped into a deep well of charisma tailor-made for a time in the ‘80s when audiences were starved for the next big thing. As a singer, his vocal range could tackle anything from Hi-NRG to jazz, fitting in nicely to the next-generation of soul singers best exemplified by Wham!’s George Michael and Culture Club’s Boy George.

Where most got an inkling of his star power would be on gossip mags and variety shows where he would be caught part of the same club scene where friends like the aforementioned George Michael, Boy George, and others like Marc Almond or Jimmy Sommerville (of Bronski Beat) would spend time hanging out in. Armed with the backing of a major label budget, it’s no wonder that albums like A Year Has Many Days caused a stir, climbing up the chart in places like England. Now, whether the majority of his music lived up to his potential – critically, it fell short of Richenel’s aspirations.

When Epic’s attention to him fell short of expectations, Richenel would have to settle for signing to the Dutch division of CBS and play to a considerably smaller audience. It was this downsizing that, in hindsight, appears to have fueled the interesting and more personal turn in direction for what would become 1989’s Deep As Blue.

Largely working with Berth Tamaëla and Silhouette Musmin of Fox The Fox fame, Richenel found perfect co-conspirators who could understand that mix of influences he was after. In their neck of the Netherlands, soul could speak with tinges of experimental and newform dance music. What’s impressive about Deep As Blue is just how much space was given for Richenel, the singer, to come out and express himself. On songs like opener, “Drifting In The Moonlight”, written by the duo, ideas gleaned from house music and New Jack Swing allow Richenel to add these gorgeous, floating, jazz vocals that predict a new era of soul music.

Deep As Blue contains wonderfully obscure and hidden gems like “Are You Just Using Me” written by George Michael (in rare form as an uncredited lyricist) who gave him pitch-perfect material to suss out every bit of his incredible range in a manner that just sounds more multi-layered than before. Richenel himself contributes some of the album’s best tracks, tracks like “Turn My Page” that build from lite funky things into quite complex jazzy things, all better fleshed out by the yearning, soulful, strains of Richenel flowing through the track.

My personal favorite, Richenel’s “Billie” exposes a deeper current of nostalgia and a powerful sense of humanity coursing through the album. For some reason, it reminds me of El Debarge’s “All This Love” – another canyon-deep song about platonic love through music – tapping into that same power universe by connecting intimately with his inspiration.

It’s Richenel’s reimagining of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” that cuts the closest nerve. Nearly five minutes long, each word speaks intimately to Richenel’s struggle to come into his own, as a person thought of as a “strange fruit” in his world. Speaking of the warm embrace her music gave him, of the release (and perhaps acceptance) he found in her voice, of the parallels – both high and low – he could find with her world, not one moment of this song loses its magnificent weight…to this very day. It’s a beautifully bittersweet song that shows just how much potential Richenel could aspire to.

On the rest of the album, lesser songs like “Don’t Step On My Heart” or “Red Hot Love”, songs that aim more overtly for the dance floor, might not scale such heights but they point to the direction Richenel would take later one, once he fully absorbed the influence of Spanish music. However, I wager that for those that keep revisiting this album, they do so because songs like “Someone” and “Love You Like There’s No Tomorrow” build on the earlier misty moods of the record.

Displaying light touches of Nuevo Flamenco mixed into that heady stew of jazz and soul felt earlier on the record, on such tracks Richenel draws the fiery soul out of his little-known early love and forges a new direction that sounds uniquely his. Forget the abrasiveness of his debut. Forget the uptempo, flash of his fumbling stumble through major labels and stardom. There’s just something about a simple song sung far beyond simply that suit Richenel to a tee. Our only shame: it didn’t reach us, as it stretched out for Richenel.