I hate giving you just a taste of anything but Né Ladeiras’s Corsaria has to serve as one today. Ambient and ethereal, Corsaria rightfully belongs in a certain pantheon of Portuguese music, much like the work of Zeca Afonso (and others), trying to bridge that gap between the moorless, Portuguese fado tradition and whatever new modernity was available after removing the political shackles from its landlocked culture. Yet, sandwiched between so many other little known cultural touchstones, it sadly remains little known outside its slice of the world.

Né’s story begins in Porto and Coimbra where as a young musician she grew up in the political and cultural milieu that brought about Portugal’s Carnation Revolution. Following in the footsteps of her very musical family, Né took her own first steps as a singer by falling in love with the music of Chile and learning to perform/sing the new folk tradition being born out of influential musicians like Victor Jarra and Violeta Parra.

Sometime in the late ‘70s, Né would join other friends to help start one of Portugal’s revolutionary folk groups, the Brigade Victor Jara, who she’d help create some of the eras most widely loved albums like Eito Fora and Tamborileiro. Shortly, Né would feel the stifling urge to try something else. Folk music was interesting but there were other areas she wanted to explore. In due time she’d join quasi-jazzy Portuguese folk group Trovante for a short stint, have a baby, and try her luck with even more experimental quasi-folk, quasi-prog band Banda do Casaco. There she’d start a fruitful professional relationship with member Nuno Rodrigues, who in tandem with the rest, allowed her to try her luck at songwriting and to go in avant directions, mixing tradition with ever more rungs of styles not entirely of her past.

It was around this time period, the early ‘80s, when Né would meet and get to listen to the forward-thinking music of established artists like Jose Afonso, José Mário Branco, Sérgio Godinho, and Fausto (to name a few) who were able to make that leap from the avantgarde of Portugal to the popular. After contributing great work as vocalist, guitarist, and writer for Trovante’s No Jardim Da Celeste, took her chance on a solo career. Although originally signed to a major label, EMI, she rebuffed all efforts by her record company to continue, largely, on that folk route. There was something else she wanted to try.

Drawn towards the electronic sound of her generation’s more androgynous “Pop” sound, Né would invite largely maligned (and in many ways frowned upon) New Wave group Heróis Do Mar to come and help her flesh out new songs that seemed inspired by more elemental things. The label wanted a Portuguese “Rita Lee”. What they got was something more in tune with the slippery ambient pop of Joni Mitchell, Kate Bush, and Japan. Songs like “Húmus Verde” and “Holoteta” would be written. 1982’s Alhur EP presented this fascinating fourth world idea of Portuguese music (symbolically stamped by the presence of future great Carlos Maria Trindade adding his magic here).

Shortly thereafter, Né would continue on with the aid of Pedro Ayres Magalhães, guitarist from Heróis Do Mar as producer, releasing a single for what would be her first full album. “Sonho Azul” posits an evolution. Now rolling in fully the influence of jazz and soul music, 1983’s Sonho Azul shares in that joyful sophisticated romp that Heróis own Mãe revelled in that same year. This was this newfangled techno pop as revolutionary music. Songs like “Tu E Tu” and “Hotel Astoria” positively groove, joining “Sonho Azul” as other “should have been radio or dance floor hits” if only her financially-strapped (but artistically-driven) label, Valentim De Carvalho, had the chance to promote them. Yet, still inside such albums, gorgeous, timeless songs like “A Aliança” and “Em Coimbra Serei Tua” still exist for those weaned on the past. Trading her folk garb for fashion-forward attire, Né found herself too far ahead of the curve (in spite of her music effortlessly navigating both currents).

For two years Né was left rudderless by the lack of success of her full-length debut, outside of its title track. She’d do a bit of work on Zeca Afonso’s masterpiece Galinhas Do Mato but surprisingly no one else came asking for her input. It wouldn’t be until 1986 that Rui Veloso reached out to her to record “Dessas Juras Que Se Fazem” to coax her into singing that song as a Eurovision entry, that we’d get to hear anything of her. Somehow, that unreleased, gorgeous ballad, sung quite lovingly by Né did what they thought was little possible and got up to fifth place in the competition (competing as Portugal’s entry to the whole shebang).

In 1988, Né began to take steps back into her own compositions and recordings. First she’d work on songs via the alias Ana E Suas Irmãs, an idea proposed by her ex-Banda do Casaco bandmate Nuno Rodrigues. Another revolutionary, evolutionary, step, it’s track “Nono Andar”, hinted at neoromantic ideas (perhaps of the John Cale-type) that would suit a new, more personal direction that might be even more unique to whatever else was out there.

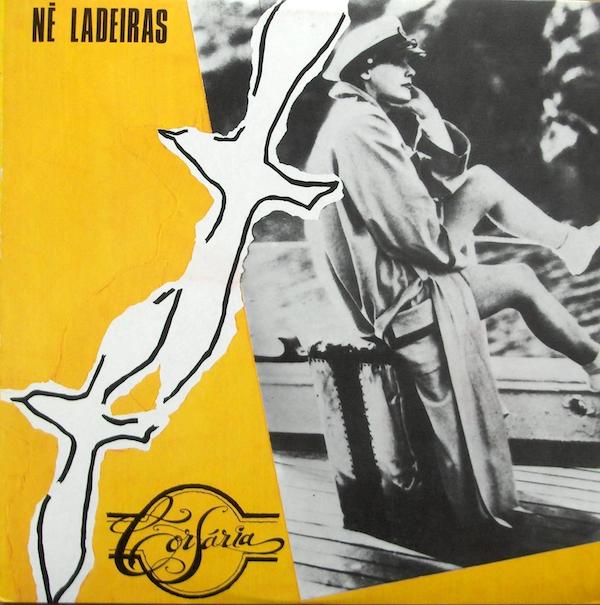

Later that year she’d take the opportunity afforded to her by the risk taking Schiu! record label and stake out to make a record almost completely by herself. Largely esconcing all easily identifiable “folk” instruments she’d dive into the world of synths, samplers, and drum machines, with the help of little-known minimalist Portuguese composer Luis Cilia with arrangements and production, trying to create a fantastic sonic world to tackle inspiration from the life of Greta Garbo and the lyrics of friend, Alma Om. Somehow, this somber, melancholic actress became the source divine for all the mysterious, spectral embers of music found on Né’s Corsaria.

It’s hard to describe the sound of Corsaria. Like the work of Gabriela, Anamar (a more obvious one), or Silvia Iriondo, it is the space between words and sonic sweetening that does the talking. “Madrugada”, the album opener, is merely three tones and a resonating drum machine building to some lush yearning padding we’d like to call a ballad. The title track takes the emotional pull of Suicide — talking about the band here — and uses minimal organ soundscapes to create her own bracing form of singing drama. Somehow, the whole A-side builds by deconstructing itself.

“Garbo” is nothing more than just a pulse, some chants, and a rustling bellscape only driven out by sampled sea sound and thunder. Yet, it’s entirely engrossing, and ghostly, unlike little else I can think of. “Mar” cements her brilliant ideas even further by creating secular spirit music that ascombs the This Mortal Coil/Dead Can Dance-lite pretences of lesser artistes, digging into her own tradition for spectral crumbs that could mutate into this world of found sound and powerful bits of melodic entrancement. Swaying to and fro, it perfectly captures the visionary “seafaring” ambient pop ideas of the album.

The flip side of this album has its own pull. “Cruz” uses the minimalist polyrhythmic ideas of Africa to create its own stake into a different, imagined world. “Sedutora” sounds like a dream of a piano ballad, half-here, half in some far away slowly dissipating cloud. To describe this album as melancholic would miss half its measure. “Jag Vill Vara Ensam” ends this album entirely in the native tongue of its inspiration, finding her own multi-track syllables to finally state this was the album she was born to make — an album and song made charting her own territory.

Now, whether others can go back and follow her due course is another thing…