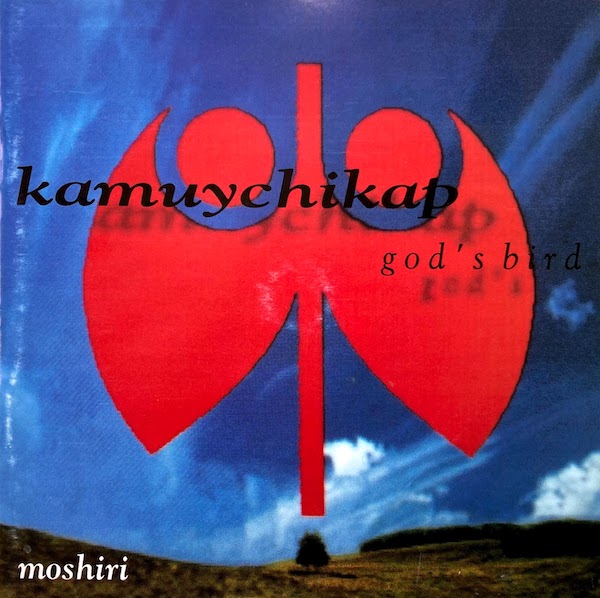

What is a protest song? Hopefully, as our musical tastes have evolved, one can recognize how the best protest songs are those that abandon any form of sloganeering for something far more personal and in many ways more multi-layered. Moshiri’s Kamuychikap (God’s Bird) isn’t ethnic music. It’s not folk music or traditional song. Moshiri’s Kamuychikap (God’s Bird) is “protest song” disguised as contemporary Ainu music. And, of course, it wouldn’t be on this blog if it didn’t have something special that transcends all of that. It’s funky, experimental, hypnotic, and searing yet serene, pointing directly at its direction guided by one creator.

Moshiri is the stage name of the sometime 12-piece Ainu supergroup led by composer, philosopher, entrepreneur, and spiritual leader, Atuy. Atuy, who’s legal name is Masanori Toyooka, was born in Shiranuka, Hokkaido, in 1945, to an Ainu mother and Japanese father. From an early age he experienced the frequent ostracism and racism directed at Japan’s Ainu minority by the Wajin, Japanese majority.

Not entirely Ainu or “Japanese” enough for his peers, Masanori had to deal with a wide swath of issues beyond his control. Abandoned by his mother and raised by his destitute father, Masanori left school at a very young age to pick up the wood carving trade with his uncle. It was only through music, something he picked up by picking up an abandoned acoustic guitar someone left in a dumpster, that he could comfort his troubled mind. By age sixteen Masanori had already decided to forgo any formal education and travel abroad to make his living. All across his travels, that informal training in music and performing for others allowed this once shy boy to come out of his shell to present his wood carvings and sing improvised Ainu songs to others.

It was in the late ‘60s when a crew from a Japanese TV network discovered this young man who wanted to reintroduce Japan to the culture and living of the Ainu. Now going by his Ainu name, Atuy (meaning “the sea”), Atuy would perform more improvised Ainu songs on his guitar in front of his largest audience, on network television. Shortly thereafter, Atuy would travel the world trying to get to know and meet other ethnic minorities across the Americas, Asia, and Europe. By the early ‘80s he’d gained notoriety playing in Canada, New York, elsewhere, and more importantly, Japan, by singing and composing songs in the Ainu language and kickstarting the launch of Ainu-led dance troupes. All the time abroad had also broadened his musical horizons, allowing him to realize that his traditionally-minded music could in fact be remade and reimagined with contemporary ideas.

At home playing in a concert hall or out in nature by the lake, it was at a jazz festival that Atuy met Akira Sakata in 1983. At that moment in time Atuy had long punted recording his music. Unattracted to the many demands various record companies asked of him or the many opportunities that rang false to his creativity, for the longest Atuy refused to sign with any record label. That changed when he met Akira.

As stated in the album’s liner notes, over twenty years had passed since his first introduction to Japanese audiences, by then Atuy had managed to rebuff every single recording offer laid at his feet. In the end, he wanted to be able to completely control that vision, his vision, which would be heard through his music. In Hokkaido, Atuy would instead create a creative space/coffee shop dubbed “Uchujin”, self-funding his own recording studio and record label.

Rather than release music under his own name, Atuy would gather a crew of gifted Ainu musicians from all rungs of life and experience to create a band he’d dub Moshiri (in honor of the word Aynu Moshir which meant the land of the Ainus). As Atuy would attest to, these songs were written when he was much younger and still green to the world. Now older and more assured of his gifts, he was unafraid to write Ainu music that could shapeshift with newer instrumentation, that could take traditional instruments and play with foreign influences, drawing them into the Ainu sphere.

Kamuychikap (The Bird of God) was inspired by the ecological environs of Hokkaido and the sensibility of Ainu spirituality. It would be the first volume of what would become thirteen records dedicated to promoting Ainu rights and fomenting a distinctly modern aesthetic to nearly forgotten age-old songs. Akira Sakata jumped at the chance to stretch out his more modal sax phrasing, developed on records like Plankton, over Atuy’s music that appeared of the same liege.

On songs like the title track and “Rera Kamui Yayeapkaste (Wind God Traveling)風神の旅” Atuy wrote compositions that had a certain flair that allowed Akira to take inspiration from the Ainu’s revered idiophone the Mukkuri, a relative of the jaw’s harp. If it sounds funky, it’s because the Ainu melodic tradition had a certain groove to it that Atuy felt was ripe to explore.

Songs like “Shirokanipe Ran Ran (Silver Rain Falling)銀の滴 降る 降る” and “Ihunke (Lullaby)子守歌” take a more leisurely pace to unfold, using those same melodic scales know for their sorrowful feel or their dreamy quality. Where in the past the passed on music of the Ainu and Atuy would use mostly traditional instruments and guitar, here they were largely absconded, replaced with a phalanx of synthesizers played by either Atuy, Chizu Upas, Kazue Ninkarai, or Sadanori Amino. This conscious choice allowed the musicality of the Ainu folk tradition to sound like a revelation to those foreign to its movement.

You wouldn’t think so, but the album appeared to be recorded in one day at Atuy’s coffee shop. That live feeling, far removed from the straight quantization of sequenced music, lends a special flavor to the album’s two final tracks, stellar highlights that still sound as powerful today as they were when they were recorded.

On “Pewtanke (We Ainus Protest)危急の声「アイヌに民族権を!」” a powerful mantra intones the rights of Ainus to be recognized as an independent race and for its culture to be unhinged from the Japanese attempt to assimilate their land and people. The music, fittingly, pulsates with heavy drum machine patterns and yearning atmospheric pads that pull at the creases those martial vocals entone.

Then the album ends with the clearest sign of respect and foresight Atuy could have chosen to make this his first recorded musical statement. Taking an oral song he originally heard collected by the late, great Ainu ethnographer and politician Shigeru Kayano, sung by an older woman who was simply passing it along orally as it had been for ages, here Atuy attempted to arrange that song in his own way.

Remaining loyal to the Ainu language’s cadence and rhythm, “Moyuk Kimunkamui (Mujina & Bear)アイヌ神話「ムジナとクマ」” this song relating another age-old myth, this time about a badger and a brown bear, just grabs you by the arm and tries to see if you can shake it’s call and response, just as the music of Nigeria did, just as the choral folk chants of Bulgario do, just as so many other cultures are trying to remain living in a dying world, hang on every last word. For 17-odd minutes one can imagine taking flight just as the Kamuychikap did, just as Akira Sakata’s clarinet masterfully does in its musical bridge, to oversee God’s earth, creation, and light. Once you’re in the pocket, it seems the stories that come out of you have, seemingly, no end in sight. So, here’s to another creation story to share.