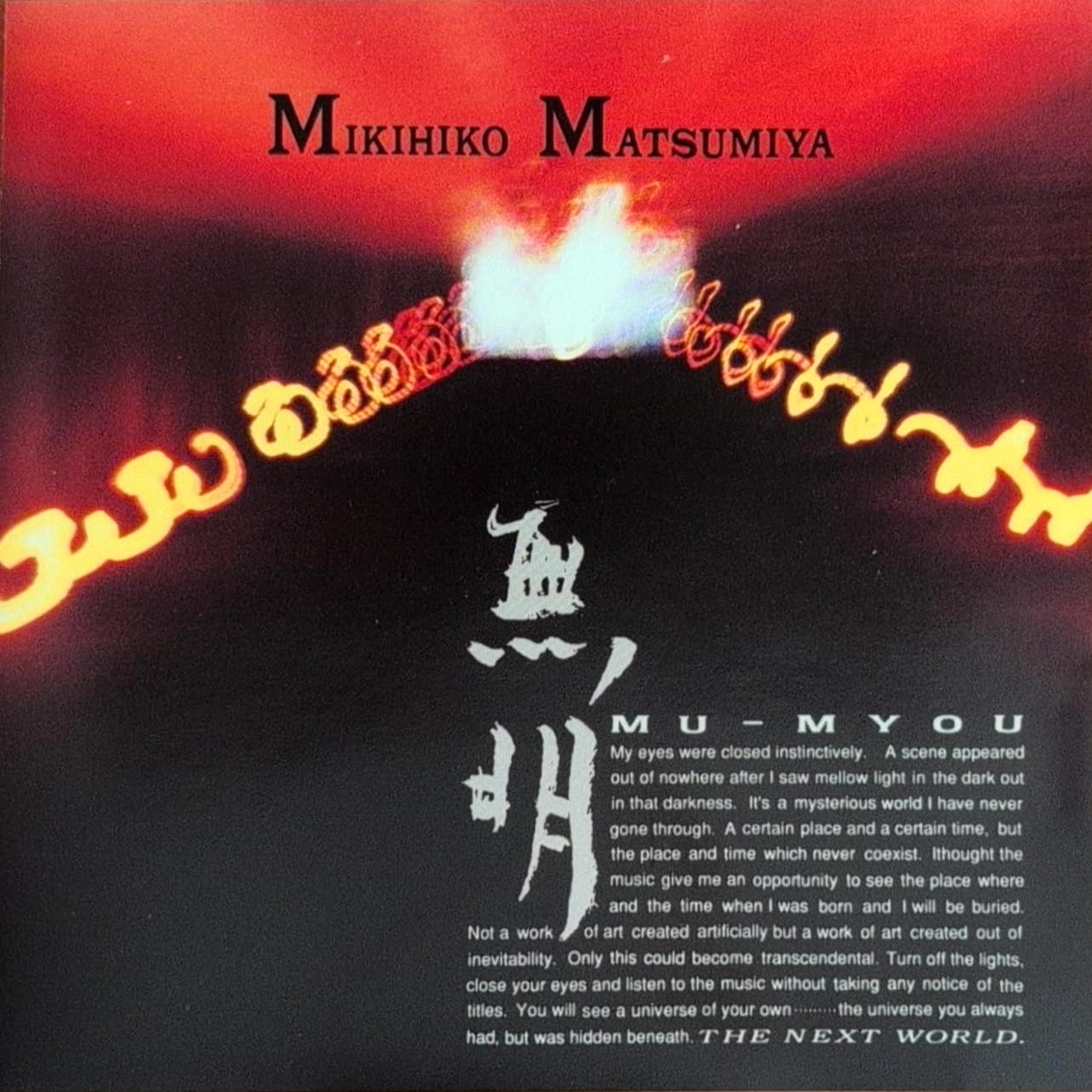

Don’t you just love listening to something that isn’t easily categorized? When I listen to Mikihiko Matsumiya’s 1994 debut, Mu-Myou (無明), I spend a moment trying to figure out what kind of music I’d like it to be, only to find that music has a right to remain mysterious and this haunting, lovely, album is what it is.

You wouldn’t know it from what Mikihiko is most famous for now, but there was a time before he was known for his gentle, relaxing, easy-listening music—largely played on ukulele. Back then, this technically gifted Tokyo guitarist, a specialist in various plucked string instruments, was doing things with those same tools that might make his current audience blush. And you could argue it all started during his formative years at Shinjuku’s Waseda University, where he studied under one auspicious teacher: Masayuki Takayanagi.

If you’ve encountered the late, great Masayuki Takayanagi’s name, it’s likely due to his revolutionary role in Japanese jazz guitar. Whether performing alongside J-Jazz luminaries like Ryo Kawasaki or Sadao Watanabe, or leading avant-garde projects like his New Direction Unit, Masayuki evolved from a traditional jazz guitarist into a trailblazer of noise, free improvisation, and experimental music. By the time his life and career ended in 1991, his guitar had transcended its role as a mere instrument, becoming a vehicle for deconstruction, a sculptural tool for reshaping sound.

Mikihiko dedicated Mu-Myou to Masayuki’s memory, releasing it three years after his teacher’s passing. On this album, you can hear how Mikihiko explores new ways to convey atmosphere and emotion—expressions his teacher might have appreciated.

For me, I keep coming back to a blurb written by music critic Hisato Aikura about the album:

“It is not that something new is born. The universe has always been there, just as it is. The guitar of Mikihiko Matsumiya sheds light on that space.”

Simply put, Mikihiko wrings all sorts of noises, drones, and textures from his endlessly sustaining Fernandes electric guitar. The result is music that feels simultaneously grounded in memory and lifted into an otherworldly plane. It’s often described as “New Age,” but that label doesn’t quite capture its complexity.

Take the opening track, “紫君子 (Shikunshi).” Here, transcendental music emerges not through tonal melodies but through textural resonances, teased from the vibrations of his guitar. As a listener, you’re left unsure where his guitar ends and something else begins—a liberation from expectation that allows the music to simply be.

Tracks like “薄桃園 (Hakutouen)” and “花凡天 (Hanabonten),” loosely translating to “flower music,” envelop you with layered textures – tape recordings, sampled sounds, and Mikihiko’s mercurial guitar tones. Played softly, this music can feel soothing and ephemeral. Turn up the volume, and its grittiness reveals a visceral, almost primal undercurrent.

Intrepid listeners might hear echoes of Mikihiko’s style in experimental guitarists like Dustin Wong (and fellow F/S reader), ECM stalwarts Terje Rypdal and Bill Frisell, the sculptural work of Adrian Belew and Fred Frith, or fretboard icons like Robert Fripp. Yet despite hints of jazz, pop, or world music in his past, pieces like the title track and “荒世 (Arayo)” feel driven by something less tangible – a ghost in the machine, or in Mikihiko’s case, the guitar pickup.

By the time you reach the closing track, “卍× (Manjibatsu),” you might find yourself thinking, “What the hell did I just hear?” But that’s the beauty of it. It’s organic in an inorganic way and vice versa. Great teachers like Masayuki Takayanagi may have pointed the way, but wise students like Mikihiko Matsumiya take us somewhere new—places where inspiration can bloom for a next generation.