My apologies to all those readers expecting a well-researched entry about Mélange’s Passion To Poison. It appears I might fail in myriad ways today. I say that because just like many of you, I too can get easily sidetracked when exploring certain rabbit holes. And in today’s case, it’s the way we or others feel the need to change part of their own identity to appeal to others.

There’s a specific period of Japanese music I’ve been fascinated with lately. It’s that period after the ‘80s bubble burst – the so-called “Lost Decade”. It was in the early to mid ‘90s, between the rise of the internet and the start of a mass global recession, when the venues to consume music seemed to become increasingly small.

Outside of your local record store or your increasingly growing big-box store, if you can think back (or lived through this time), you can remember that radio was this thing becoming increasingly gentrified and seemingly only skewing to the hottest hits of the day. I imagine that those like me who had access to cable, experienced another side of this increasingly, hyper-constricted music market; I imagine you too can remember seeing videos on MTV that balkanized this sense of division even further.

Were you into grunge, hip-hop, or dance music? Rarely did the twain meet in whatever aired throughout the day. You had to tune into a specific programming block (or worse yet) hope your subscriber carried BET for any kind of deeper look at what was going on in the slowly malnourished urban soul scene. And worse, any personal image one had was likely filtered through a prism: “Where should I belong?”

I imagine the promise of CD-based music publishing and large multinational record companies provided was that they were supposed to leverage the might of capital to provide greater access and promotion to whatever artist was looking to become famous at a new, seemingly, ever-growing, stratospheric, level. Somehow, this song and dance would end divvying up this era of mass profit between producer, creator, and publisher.

In hindsight, what we know now is just how many musical artists were given to false hope, made to bend to certain music industry edicts, then forced to become an even smaller fish in an even larger, murkier, musical pond — only to get swept away with rise of nascent peer-to-peer technology. Japan’s record market, as you can surmise, wouldn’t be that different.

It’s that kind of market that forced certain artists and creatives to try to game or subvert the system. At least, that’s what I believe was the case for Samson Records, one-time home to the Mélange crew.

Mélange was for all intents and purposes the brainchild of Samson Records founder Masao Suzuki and drummer/dance producer Kiyotaka “Goru Kiyo” Takiyama. In the beginning, they came to the realization that a lot of the Japanese music market had begun to develop an aversion to national artists.

With all of mass media pushing the “marketability” of Western pop music, more and more Japanese-based artists were given short shrift (and financial backing) to compete with the far more lucrative money-making foreign releases that practically sold themselves as imports, domestically. It’s this marketplace that forced the members of Mélange to ask: “What can anyone trying to make it in such an industry?” They’d attempt to strike a different game to make their artists successful.

Focusing on the burgeoning underground dance, electronic pop, and leftfield scene, under Samson Records, Japanese and foreign artists were remade/remodeled domestically as foreign artists – even if the vast majority of the group or the artists themselves were largely, Japanese. To do so, album releases would be entirely sung in English or another non-native tongue (with track titles and liner notes to match the language switch).

I imagine, they thought, at that moment in time, the only way to reach a larger audience was, to quote another Biblical allegory, the song of Solomon, “cut the baby in half”, resolve the lack of national support by treating themselves as “foreign” acts.

What’s surprising about this ploy is that the artists they signed were in fact worthy of wider support and attention (and some, eventually, would sign to larger, overseas labels). However, it was in that mid ‘90s brew when Kiyo convened a crew of musicians, musicians like Masataka Matsutoya (listed here as “Mayumi”), Toshihiro Nakanishi, and Mario Umali to serve as musical backing to a group that would be led by Hawaiian-born, sometime-Hiroshima singer, Machun Taylor.

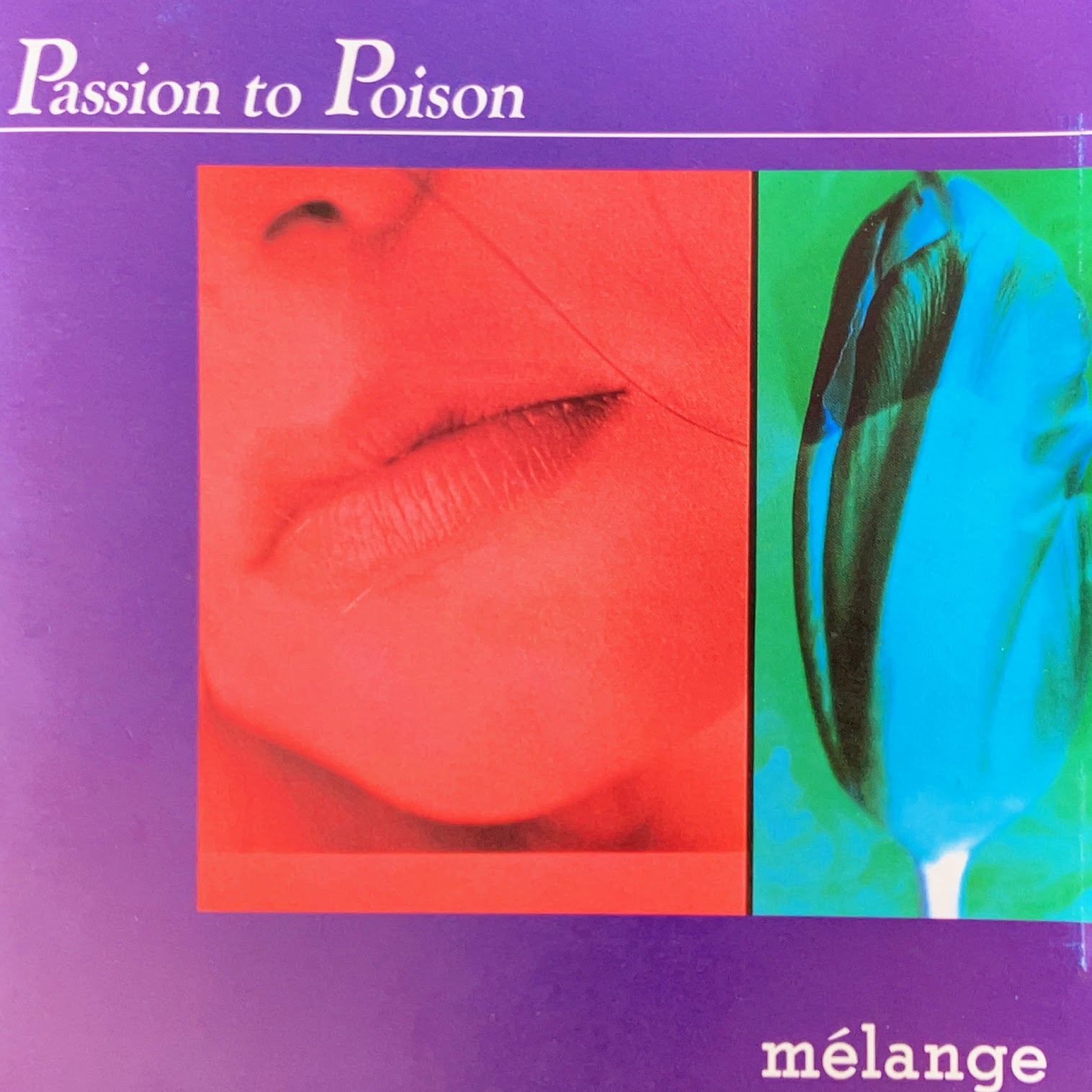

Passion To Poison was one of those sterling albums from this label that actually merits its continued revisiting. It was in 1995, when Manchun came to the studio, armed with a bunch of stellar originals and a few fascinating new standards to reimagine. It’s an that introduced itself with a wonderful, nostalgia-inducing swingbeat reimagining of Lionel Richie’s Quiet Storm heavy “Love Will Conquer All”. There you got to hear Machun’s wonderfully soulful, rich, jazz-influenced vocals and contribution. There we got a peek at Toshihiro Akamatsu’s quietly brilliant vibe playing.

One wonders how the Lovers Rock of “Come Back To Me” might have played to a Japanese audience whose access to their own J-soul music had been quietly losing ground during those early ‘90s label mergers. Would those lovely instrumental interstitials like “So Right, So Wrong” and “Rain Forest” that owe a debt to Ms. Jackson’s Janet. even exist if the Tropicalia-tinged “Flower Of Bahia” didn’t cement how Mélange’s semi-faceless group was something else, a group that could spread their artistic wings?

There’s a lot to Passion To Poison that still leaves me thinking. Just how much can one lose one’s sense of identity in order to be taken into account? And how does one’s voice speak louder than some kind of superficial body topography?

You don’t have to know much about cultural appropriation to appreciate that music has the capability to carve out its own higher culture — one where it’s not co-opting someone else’s voice. In the end, what speaks to a greater world is whether your music is good or not on its own terms. Songs like Mélange’s “Precious Days” remain a soulful conversation between a few musicians, one American, Steve Gaboury, and another from home, pianist Ryuta Abiru, trying to interpret the waxing memories heard on Machun’s voice, as one musical unit.

The thing that keeps me coming back to this record (and to the ideas it serves) is that this mix never feels like a put upon. This mélange feels like a hopeful vision. The only way we’re going to overcome a lot of what lies in their future, and our present, has to come with the way we interact with each other, in service to being heard together, to be part of a better past… Now whether their attempt was successful in the long arc of history, is a story still to be told and a judgement there to be made.

2 responses

This was an interesting read!

I was born in the early 90s, and while one can look backwards to see what happened and more or less piece something together, I often still wonder exactly those outside the mainstream felt from the 80s through to the 2000s when it was becoming clear what direction the music “industry” was heading.

Also, good to see you back posting more frequently. This blog (or whatever it is called, I’m unsure) is great.

Reminds me of the theme song ‘La la la love song’, which was the intro to the J-Drama classic Long Vacation. Want to talk about the lost decade? I feel no single piece of media more captures that vibe… I really recommend watching it and if you need help finding it in high quality, send me an email. (;

Have a good one,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGQuCyLvay8&ab_channel=ToshinobukubotaVEVO

song with intro to the drama (lower quality): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HiNQeQQJWgw&ab_channel=NinaFariza