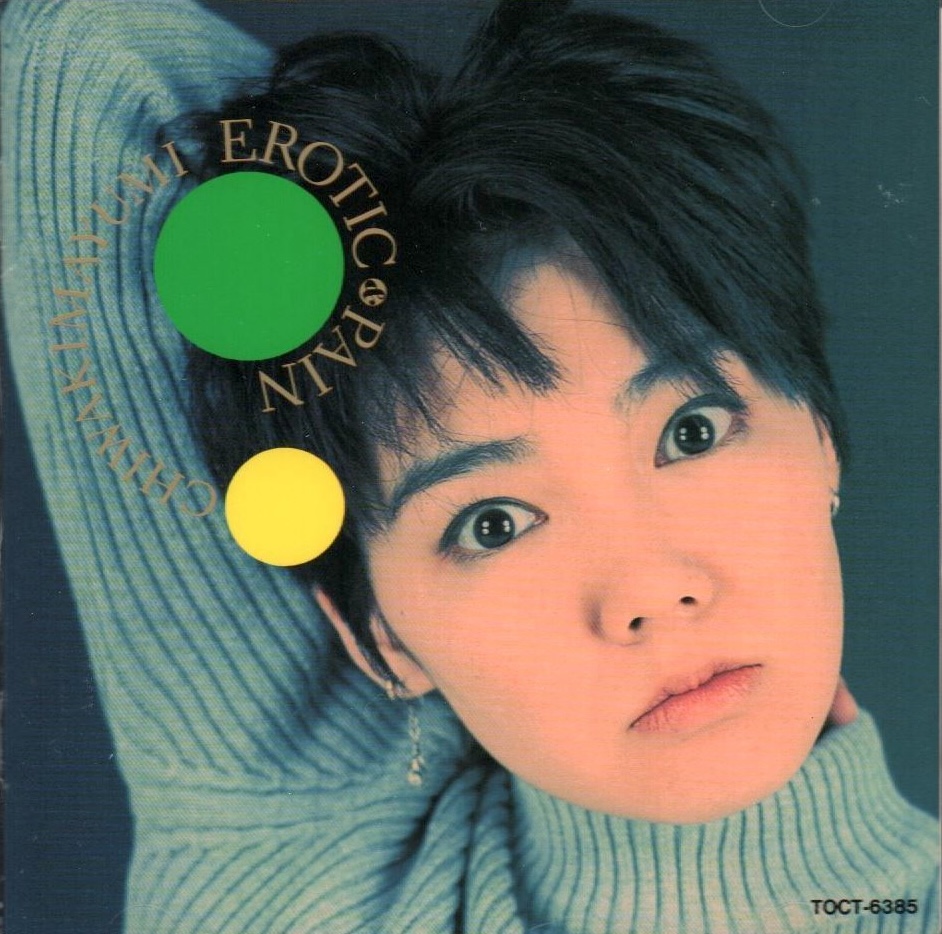

You’ve all heard this, “but it looks good on you!” We all might be loathed to admit it but certain things do fit us better. I say this, because in the world of music, we’ve all heard (or seen) certain artists spend all their life trying different musical outfits, trying to find just what sound suits them. And on special occasions, much like today, we actually get to hear them stumble into greatness, fulfilling that potential we all knew they had within them. Although that work might not be what others are accustomed to hearing from them or would be surprised to see, it’s what fits them to a tee. When I hear Mayumi Chiwaki’s Erotic & Pain all I can take away from that album is this feeling.

Mayumi Chiwaki is best known as the lead singer of Japanese ‘80s techno-pop music duo, Menu. A native of Tokyo’s Shibuya neighborhood, from a young age Mayumi always had access to and preternatural inclination to follow was at the forefront of global culture.

In the beginning, Mayumi was keen on the classic Western pop music of The Beatles and grew up idolizing glam rock bands like T-Rex (of whose lead singer, Marc Bolan, she met at age 10) and harder-nosed outfits like Led Zeppelin, KISS and other bands of that ilk. By the time Mayumi entered college she had begun to dabble in performance and music.

Under the influence of early New Wave groups like the Talking Heads, Sadistic Mika Band, and Bow Wow Wow, Mayumi would help create with guitarist Wataru Hoshi, Le Menu a five-piece unit that would whittle itself down to a three or two-piece band that would remain as Menu. Taking advantage of Mayumi’s quite spunky, punky presence and girlish vocals, Menu joined the ranks of other groups like PSY-S and Yapoos that were blazing a trail on pop charts with a decidedly more rebellious presence, ushering in the next-gen (or at least a different kind) of J-pop idol.

Mayumi would come to fame in that same era and year that Cyndi Lauper’s “unusuality” made it easier for such a quirky star to find their own footing in their own land. And like all great frontwomen, her record label thought it would be better/more profitable if Mayumi would split and start her solo career. As a solo artist, Mayumi would go deeper into a harder-nosed sound and early albums found her exploring all sorts of glammy, if not a bit out-dated, New Wave.

For a moment, it appeared that Mayumi’s career was serving up lukewarm or passable versions of other singers like Siouxsie Sioux, Kate Bush, and Debbie Harry, all great artists who had already moved on from the stylistic cues Mayumi was aping. However, it’s this solo time that would make her a household name in Japan, finding Mayumi fronting various rock shows and becoming a staple of variety shows.

Thankfully, something must have changed from the time of 1988’s Gloria and 1992’s Erotic & Pain. What that is I couldn’t exactly find explained by Mayumi everywhere I looked. However, what you can sense on Erotic & Pain is Mayumi completely moving away from the glam pop of her past, toward ideas deeply rooted in club culture. One can argue that Mayumi’s professional split from longtime record producer, Hajime Okano, allowed her to finally explore something outside of her wheelhouse.

Working with a trio of producers – Soichi Terada, Yukihiro Takahashi from YMO, and Ryomei Shirai from Moonriders – must have felt like a breath of fresh air. Of the first of those names on the list, Soichi probably had the most influence in this direction. At that moment, Soichi had been bubbling under the Japanese club world as a remixer, crafting early deep house mixes for artists like Nami Shimada or Mayo Nagata and producing what were little-known (but now seem like totemic/prophetic) albums like Akiko Kanazawa’s House Mix series. And on this record you hear his groove-centered musicality appear on most tracks. With Ryomei and Yukihiro we got to hear them contribute tracks that were less ‘80s and more experiments with techno and ‘90s dance pop.

What is the most appreciable difference about Erotic & Pain is Mayumi’s change in tone and phrasing. Gone were the high-pitched, child-like singing of her past. On songs like “Error” and “ふたり自身” a richer, lower-register, adult voice comes singing through, giving Mayumi a wonderfully sophisticated, and dare I say, lived-in perspective. Here’s where one can make the argument that all of Mayumi’s prior work would pale to what she did here. This music better fit her creative vision.

Running at a lean thirty-six minutes, Erotic & Pain, trapezes through seven tracks of expertly produced dance pop. It’s first single, “恋のブギ・ウギ・トレイン”, a reimaigining of Tats Yamashita’s “Boogie Woogie Train” for Ann Lewis, should have been a hit and appeared like it was picked up by Tokyo clubs. A spectacular highlight from the album, “恋のブギ・ウギ・トレイン”, a should have been hit fast-forwards Japanese idol culture through the world of the club diva, letting Soichi Terada and Mayumi Chikawa craft their own form of deep house music, spiriting those iconic, uplifting, Terado grooves through the nostalgic world of Mayumi.

Album opener “Error” by Ryomei Shirai reorients the listener to the ballroom, planting the floor where Mayumi could sashay herself on. Pizzicato Five’s Yasuharu Konishi joins Mayumi and Yukihiro on “ふたり自身” for a wonderful bit of art pop. Likewise, Mayumi’s “月をながめて” slows the pace down for some spirited floating bit of balladry.

Big kudos go to Mayumi for putting her mark on songs like “恋が途切れてく” an extremely baggy, Madchester-style groover (contributed by Original Love’s Takao Tajima) that would fall on its face without the right singer. On this track, that very woman takes ownership of the groove transforming its jazzy beat into a meditative self-empowered romp. The impressive Walearic “禁じられた唇” (with backup vocals by Yoshiyuki Ohsawa) impresses just as much by showing Mayumi another quill she had in her bag: the ability to fire off seductive, intimate tracks into fruition, that had little history in her catalog.

As I listen to Erotic & Pain’s final track, “恋のブギ・ウギ・トレイン(House Train Mix)” a slinkier, edgier, sexier version of the original rework, I keep thinking: why on earth did Mayumi not follow more in this direction? She’d go on to make an album that would fit into the “alterna-rock” zeitgeist but something about what she did here fit her to the tee. In the end, it appears that what we find comfortable might not be what we put on on special occasions or better yet, what we like on someone else might not always be what they’d like to hear.