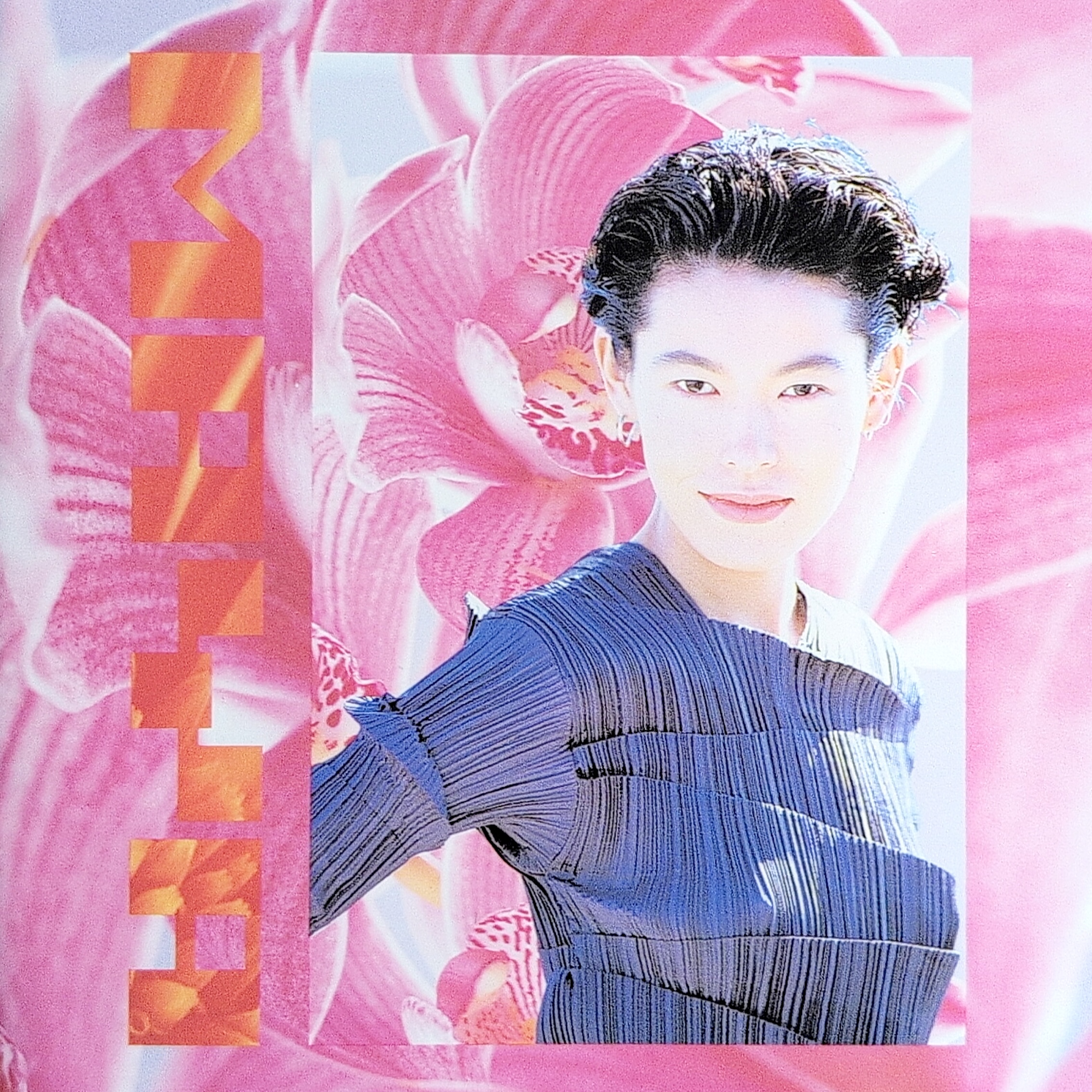

Much like many of you, once you’re done catching up with Maya Hayashi’s life, you’ll come to the same conclusion I did: glad she made it out the other end. Before her current career as a farmer and television personality, Maya had a quite short but very memorable career as a model turned singer, culminating in this impressive sophisticated Japanese pop album nearly lost to her story.

Maya Hayashi was born in 1958 in Ueda City, Nagano Prefecture, the middle child of three siblings. Her childhood was fomented in the shadow of Mount Tarō, where fresh mountain air, natural beauty, and the rhythm of rural life shaped her quiet spirit. Her parents, both elementary school teachers and part-time farmers, raised their children with care and purpose. Her name alluded to her parents’ deeply spiritual beliefs. Maya spoke of having heartfelt admiration for them—especially her father, a beloved school principal known for his poetic routine of placing fresh flowers in every classroom each morning.

But it was Maya’s mother who quietly shaped the heart of her artistic sensibility. A gifted maker and re-maker, her mother could transform old clothing into entirely new pieces—giving second life to fabric, threading love into every stitch. Inspired by this ingenuity, Maya began altering her own clothes as a child, sanding down sticks into buttons and cutting fringe into her T-shirts.

Although preternaturally imaginative, Maya was a painfully shy girl and rarely rocked the boat. She rarely spoke in class and struggled to make friends. Her transformation as a person began with an act of quiet rebellion in high school. Mistakenly accused by a teacher of breaking school rules with a permed hairstyle (her hair was naturally wavy), she followed their order to straighten it out. However, once at the hair salon, fueled by anger or frustration, she requested an actual perm—big, mega curly, and bold (to her parent’s consternation). It had been the first time she pushed back against authority. From that moment on, she no longer was the timid girl who kept to herself.

It was in the ‘80s, Maya fully embraced the fashion and defiance of Japan’s sukeban (delinquent girl) subculture, customizing her school uniform with dramatic pleats and modifying her school bag until it collapsed into a comic book-perfect-like accessory. Classmates who once overlooked her now lined up to shout at Maya in her loud and proud voice.

After high school ended, Maya moved to Tokyo, where she chased its nightlife and luxuriated in the freedom of city life. It was in Tokyo where her bad girl lifestyle found her bouncing from one job to the next, culminating into being kicked out of her dorm. At her lowest, Maya was broke, living in a bath-less apartment in Ogikubo, shaving her head to avoid maintaining it. It was a chance encounter with an old high school friend—now stylish and thriving in the fashion industry— that sparked a new idea: modeling.

Maya approached a Tokyo modeling agency, but her unconventional, tomboyish, looks and punk aesthetic made her a tough sell in Japan’s mainstream modeling scene. For two years, she hardly booked any professional or amateur work. Even at promotional events, she often stood alone by the vending machines, drinking canned coffee with the staff while other models drew photographers.

Still, she remained committed to her style and what it represented. However, living in Japan had become stifling for Maya. With just 200,000 yen to her name, Maya set off for London with all of her savings—hoping to take in the spiritual home of her beloved punk fashion. It was during a brief flight stopover in Paris, that Maya changed course, and impulsively called a Japanese designer who lived in Paris, Sueo Irie (a close friend of Japanese fashion design icon, Kenzo, and founder of Irié), and asked him to take her to grab a cup of coffee. It was Irie, who’d take her to Café de Flore, a legendary Parisian haunt for artists and intellectuals, and change the course of her story.

There, fate intervened again and her sort of reckless move paid off. While drinking coffee a stranger approached her, letting her know that she had a unique face, offering to her a photoshoot. That man turned out to be Peter Lindbergh, one of the most celebrated fashion photographers of the 20th century doing some unlikely headhunting.

Within weeks, Maya had joined a Paris modeling agency and was appearing in Marie Claire, turning out to be the first appearance of a Japanese model for that publication. Her unconventional beauty—once ignored at home—made her stand out in the fashion capital of Europe. Maya would go on to walk in Paris Fashion Week and became a celebrated figure abroad. When she returned to Japan, she was embraced as a “reverse import” success story, booking high-profile jobs and magazine features.

But with fame came a certain degree of ego. Maya’s rise in international stature found her appearing in shoots for designers like Jean-Paul Gaultier and Kenzo, but her newfound fame in Japan proffered many opportunities that came with double edges.

At her height as a model, she’d skip rehearsals, limit photo takes, and carry herself with a diva’s swagger. Maya spent extravagantly—hosting parties, flying first class, and buying designer clothes without checking price tags. And unbeknownst to many, she wanted to capitalize on her fame as a model to jumpstart a career in music. She had fallen in love with singing while walking down the runway to Dave Brubeck’s “Take 5,” and longed to express herself as a singer and songwriter.

In the battle over which Japanese record label would take a chance on Maya’s next experiment, Midi Inc. won out, signing her to record an album in both Japan and France. Whether they hoped to capitalize on both markets or to tap into a growing Japanese appetite for homegrown French-influenced artists, whatever the reason, Maya found herself with the unenviable task of trying to bridge the gap between Paris and Tokyo—and her own wants and needs as an artist.

What strikes you first about her 1991 debut, MAYA, is just how different Maya’s voice truly is. Belonging to the school of Sarah Vaughan—a gradient tone from black to white—it was Maya’s husky, smoky, and jazzy phrasing that placed her in a different league of Japanese singers. One would be hard-pressed to categorize what kind of music she was making based solely on her voice. Singing in two unlikely languages—French and English—Maya’s lyricism was much like her: hard to pigeonhole. And her choice of music to sing over was equally impressive in its variety, capturing many intriguing niches in dance music being fomented in the early ‘90s.

Working with producer Takashi Sora, best known for his work on Akiko Yano’s Welcome Back—an album that shares some of MAYA’s free-spirited energy—they explored Maya’s many musical sides, revealing a singer with mercurial taste. For the sessions held in Japan, arranger and musician Chokkaku brought a certain edge, sophistication, and sexiness that felt more cosmopolitan than any J-pop being created at the time. For the sessions in France, Maya was paired with a surprising musical companion: Pierre Bensusan, who infused the music with a deep French folk aesthetic.

Altogether, MAYA turned out to be a successful musical experiment, even if the market didn’t treat its release as kindly in terms of sales.

When I look for better-known spirits in Maya’s world, I turn to artists like Sade, Viktor Lazlo, and Rosie Vela—head-turning women gifted with more musical brains than even their looks would suggest. Opening track “Photographable” speaks to a certain genre I’ll call fashion music: music that revels in the oft-derided, misunderstood art form of fashion, sculpted for the runway. On this rollicking, sophisticated soul track, Maya unfurls her velvety voice, celebrating the empowerment found in taking control of one’s visage and image.

In another original, “Murmur,” Maya reflects on the importance of drifting within oneself—opening borders to new energy. In this sun-kissed jazz track, Maya’s easygoing philosophies float through in music that sashays as gracefully as it moves. Her cover of Bryan Ferry’s “Valentine” impressively amps up the original’s tension, morphing it into mutant funk, transforming it into something distinctly hers through reorientation. Likewise, her take on the smoke-filled-room jazz standard “Black Coffee” showcases the depth of her vocal tonality.

What sets Maya apart from so much noise are tracks like “Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word.” If you’ve heard the Elton John and Bernie Taupin original, you’d be hard-pressed to imagine it reinterpreted so starkly. Yet on Maya’s lips, and in Chokkaku’s arrangement, they inject a kind of Walearic saudade—lifting its nocturnal tempo into something more memorable and palpably aching than the original. “Alive On Killer Rhythm,” written by Chris Mosdell, keeps that pulse alive—another runway-ready piece of dance pop hitting the same dramatic, angular notes as Grace Jones in her heyday.

MAYA wouldn’t be MAYA without acknowledging the risk Maya took in shifting its course completely by tapping into her “French” side for a detour into folk-inspired music. “Prés De Paris” signals that turn, as Maya, Pierre Bensusan, and percussionist Dou Dou Congar reimagine one of Pierre’s totemic folk songs—channeling that historic link between France and Africa. And in the center of it all is Maya Hayashi’s shape-shifting voice, rekindling that connection in a bold new direction.

Equally impressive is the next track, “Reels,” where Maya gives voice to another Pierre original, landing gracefully on an unexpected—but true—Gaelic inspiration. In a bit of boundary-blurring experimentation, Maya and Chokkaku reinterpret Jean Sablon’s golden-era French standard “C’est Le Printemps” as a bite-sized electro-pop cabaret piece, tailor-made for her voice.

Spiritually, the album ends with just one voice—Maya’s—and one guitar—Pierre’s—taking on Michel Legrand’s “You Must Believe In Spring.” Riding the same wavelength as Bill Evans and Tony Bennett, they look past the song’s melodic flourishes, diving deep into its lyricism to find something more intimate, something close enough to feel whispered.

Maya would later share that after the commercial failure of this album, her life spiraled. Overspending led to massive debt. As high as her fame had once taken her, it all came crashing down. Struggling to survive, she once resorted to eating cat food. Battling eating disorders and public scrutiny, there came a moment when Maya stood at the edge of Aokigahara Forest near Mt. Fuji, ready to give up—until her husband talked her down.

Thankfully, Maya rekindled her love for life in its soil. Various odd jobs, sometimes working under a false name kept her going, then one day she discovered farm work—and realized that’s what she wanted to do. Today, we find her working the land, extolling the virtues of growing produce, even rekindling her modeling career in this new chapter of her life.

And we can only hope that this lesser-known part of her journey—when she had another kind of voice—is rediscovered for what it was: a kind spark, still flickering, ready to burn brighter once again.

Reply