Much like many of you, the more time one spends in nature, the more one begins to hear a certain musicality in the earth itself. Whether it’s in the rustle of fallen leaves, the whistle of wind through branches, or the faint bird calls that seem to drift from nowhere, one is never truly alone in “quiet.” The environment always conjures a symphony of its own. For those who engage in field recording, capturing such moments requires more than just holding out a microphone—it demands true listening to express the world through sound.

As the year winds down, I’ve been reflecting on this thought, which nudged me to share something I’ve quietly collected over time but rarely shared in its truest form: environmental music. This kind of music seeks a delicate balance between the sounds of nature and musical composition. Today, I want to introduce you to a little-known work by Osaka-based multimedia composer and artist Masafumi Nanatsutani.

In 2006, Masafumi began his Water Planet series, a collection of ambient recordings inspired by one question: “What is seseragi (せせらぎ)?”

If you’ve ever wandered through rural Japan, you’ll know that stepping into a forest or pausing by a river reveals the country’s riches in the freshwater coursing through its young landscapes. Whether it’s the murmur of a brook or the steady rhythm of ocean waves, such moments invite us to connect with nature on a deeper level. In Japanese culture, seseragi isn’t just the sound of flowing water—it’s a lingering sensation, a translation of water’s murmurs into a calming, restorative energy. This idea inspired Masafumi to visit countless streams in one of Japan’s ancient capitals, Nara, and distill this essence into his recordings. Using binaural microphones, Masafumi would return to his studio and perform music designed to “harmonize and match the pitch of flowing water.”

On his first album, Water Planet 1: Dawn, Masafumi ventured to Tenkawa Village, a waypoint for many pilgrims hiking Nara’s stunning mountain trails. From 2 a.m. to 6 a.m., along Mount Ōmine’s Yayama River, he captured the sound of spring rain gently replenishing the riverbed. His second album, Water Planet 2: Noon, continued the exploration in Totsukawa Village, a remote settlement nestled along the Kumano River. From early morning to late afternoon, the river’s character unfolded through bird song, rustling leaves, and the rhythm of forest winds as it wove through mountains and valleys before reaching the Pacific.

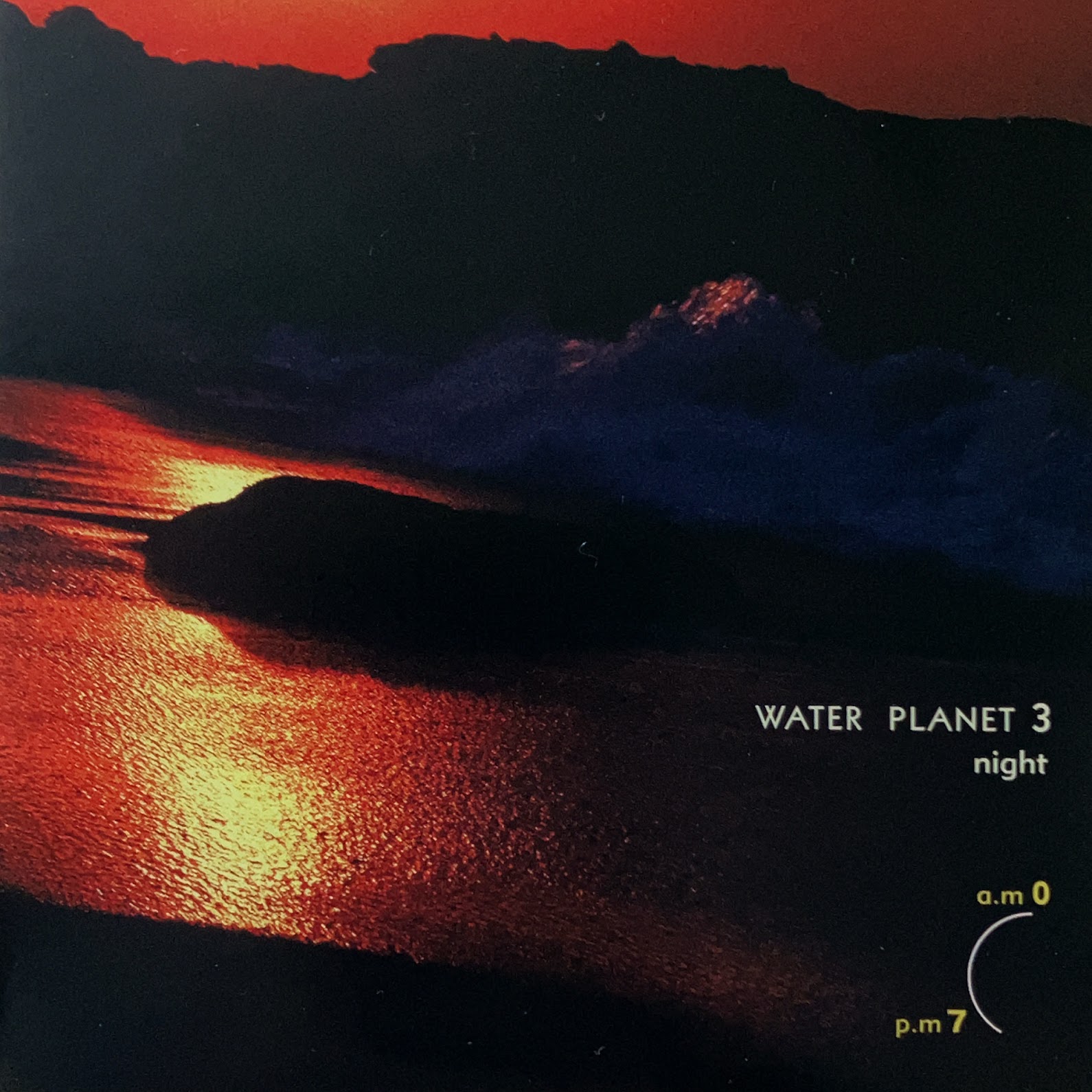

Water Planet 3: Night, the album I’ll share with you today, concludes the series with recordings from the “Gorogoro” spring waters around Mount Sanjōgatake, better known as Mount Ōmine (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), in Yoshino-Kumano National Park from April through May, later that season. These softly flowing, mineral-rich waters—emerging from Goyomatsu limestone caves, feeding Dorogawa’s Onsen baths, forking the Mitarai Gorge, then forging with the “Milky Way/heavenly river” Amano-gawa—are said to harmonize with the body’s own rhythms. Recording in near-total darkness, from 7 p.m. to midnight, Masafumi sought to capture the music of “natural quiet,” free from the interruptions of modern noise like cars or planes. The only adjustments he made involved positioning his microphone to replicate the exact balance of sound (its sonic volume) as he experienced it.

As with the other albums in the series, Masafumi returned to his studio to compose music that would enhance and reflect the landscapes he had recorded. Guitar, piano (occasionally played by his partner, Yumi Nanatsutani), and sparse electronic synths were added to evoke the textures, memories, and emotions tied to these places.

On this record, for 40 minutes, listeners are invited to synchronize their minds and bodies with the rhythm of the largest part of our earth trickling down its smallest corridors—not just to hear it but to experience it in a way that feels personal and profound. How we achieve this, of course, is the grand question. For now, I’ll leave you with Masafumi’s thoughts on the hows and whys of this work, translated from the original CD release:

“The word “seseragi” (the murmur of a stream) evokes feelings of gentleness and healing. Many people have likely experienced a sense of calm when listening to the sound of flowing water in a forest. But can the sound alone replicate the same feeling as actually being in the forest? The first time I recorded and listened to the sound of a stream, I was shocked. “I can’t tell what this sound is. It just sounds like noise. It sounded fine through headphones, though.” Perhaps the reason why the word “seseragi” feels pleasant is that it conjures not just sound but also visual imagery. This realization sparked my desire to express the soothing essence of a “seseragi” purely through sound.

The sound of a stream after rain, carrying sediment, is soft; a pebbled riverbed produces light and slightly high-pitched sounds, while a mountain stream flowing between rocks creates deep and muted tones. The sounds of water possess an infinite variety of timbres. Depending on the time of day, night, or season, as well as the condition of the riverbed—whether it’s covered with twigs, fallen leaves, mud, soil, or stones—the sound of the water changes. Even shifting the microphone by a few centimeters produces a different sound. When we encounter the murmur of a stream or natural sounds in the mountains or forests, we’re actually listening to countless layers of sound information simultaneously.

For this recording, I used a supercardioid shotgun microphone, positioned about 5 cm above the water’s surface, moving it in 50 cm intervals. Multiple recordings of water sounds were made simultaneously from at least five different points (or more), including microphones placed away from the stream and aimed at the surrounding air. By playing these recordings together, I aimed to recreate a more natural “seseragi” sound. I balanced the volume so that the sound of water near the surface was most prominent, while strong currents or waterfalls were placed further in the background.

The sound of spring water or a gently flowing stream is very faint and often requires significant amplification, even with highly sensitive microphones. This means that even in a mountain setting, distant car sounds can seep into the recording. During the day, airplane or helicopter noises—typically unnoticed—become distracting. I chose Yoshino District in Nara Prefecture to achieve a state of “natural quiet,” free from artificial sounds.

The music in this work has two main purposes. First, it blends with the water sounds to evoke a sense of landscape color and temperature. Second, it enhances the spatial dimension of the water sounds. The recorded water and environmental sounds were only adjusted in volume and positioning; no additional effects were applied to create spatial audio. Instead, the music adds depth and extends the distance between the natural sounds, achieving the desired effect. The performance was done while listening to the water and environmental sounds, aiming to harmonize with the tempo and pitch of the flowing water.

This Water Planet series is divided into three themes: early morning, daytime, and night. A shared theme across all three is “flow” and “circulation.” The flow of the stream, the passage of time, and the flow of energy in the forest or mountains are not simple repetitions but cyclical processes that evolve with each iteration. Starting with the sound of rain in Volume 1 and ending with spring water in Volume 3, the series expresses one complete cycle. Each volume reflects the passage of time through changes in environmental and stream sounds, illustrating the flow of energy.

Through the process of recording and editing, I realized that the sound of flowing water doesn’t simply soothe—it loosens, revitalizes, and energizes the body. I felt as though it flushed away impurities in the body, replacing them with a fresh, airy energy. The flow of a stream seems to synchronize with the circulation of blood in the body.”

May 16, 2006

FIND/DOWNLOAD