If you can, allow me one more diversion for the year. In my last post, I finally found words to describe what was my album of the year for 2022. Now I’m cycling back to an album that truly lingered in my headspace just as long this past year, 2023. It’s an album marked by my faith: that some of the best music – the one that really sticks with you – does so by tapping into a grander sense of purpose, for us as listeners. That of a shared universal language easily understood by all, that can speak for those who can’t verbalize it. It’s in this belief that I hang my hat on Martin Destrée’s Entre Chien Et Loup.

As one listens to Martin Destrée’s Entre Chien Et Loup, one can sense or suss out certain themes – those that ruminate within us – those of our eternal struggle between the light and dark within all of us. They’re these spheres that impart a certain flavor to Martin’s music. It’s the push and pull of trying to figure out just what is our purpose and how much of that is tied to righting the wrongs in the world (while balancing simply living/surviving in such a world).

From the fortunate little we know about Martin Destrée (real name, Martin Terrier), she was born and raised in Aix-en-Provence, to both Indonesian and French parents, in the famous locale of Côte d’Azur, along southern France, a stunning mountainous region that inspired another one of its own: Paul Cezanne. As a singer and songwriter, Martin’s taste in music appeared rooted in the Chanson tradition. However, as her career shook out, it gravitated towards more malleable territories like jazz and soul music. Yet, underlying it all, as history would lay bare, Martin’s ties to different kinds of devotional music appeared to form a much closer and lasting source of inspiration.

Early on, in 1985, Martin tried to fit in as a singer into France’s New Wave scene with singles like “Je N’Aimais Que Vous” that cut a straight line between her jazzier inclination and the more ephemeral French pop scene. It was in that single’s B-side, “Sunrise”, one could hear a certain direction that she sounded far better suited for and more in the spirit of her creative vision.

It would be two years before Martin would find her label willing to let her explore that more nebulous path. In 1987, one can kind of sense what her major label was trying to steer her towards. Martin’s music appeared to not fit much of any musical current or trend flowing then. Trying to capitalize on her exotic looks, Philips gave it another go, trying to mold her as a sort of French Chrissie Hynde, providing her with the kind of record budget backing to bank on such an investment. Yet, to Martin’s credit, she strayed further from the path they envisioned for her. Martin furtively followed whatever her north star was.

Martin’s next single would be, “Manolo”. Backed by a wonderfully cheeky music video, it became a quiet club hit. Unlike the dated sound of her earlier single, “Manolo” found Martin embracing the elegant phrasing of her singing voice and the seductive mystery of her mercurial lyricism. Backed by more learned musicians, they seemed to understand the kind of alternative jazz and rock music Martin was imagining and shifted sonically in that direction.

Credit to Martin for taking her time to figure out just what would become of her major label album debut, Entre Chien Et Loup. For three years, Martin would work with songwriter, Philippe Brunet, and heralded old-school chanson producer great, Mick Lanaro of Claude Nougaro and Leo Ferre fame, to round-up musicians and conjure up a sound that felt uniquely hers.

In some versions of this album’s release, Martin speaks of trying to create a collection of songs that hovered between the realm of shadow and light. “Entre chien et loup”, famously, is that French idiom for being caught between the crepuscule. Inspired by the “open road” musical ideas of one Joni Mitchell, Entre Chien Et Loup served as Martin’s attempt to travel further down that journey, to express her own Hejira rooted in whatever vistas that would inspire.

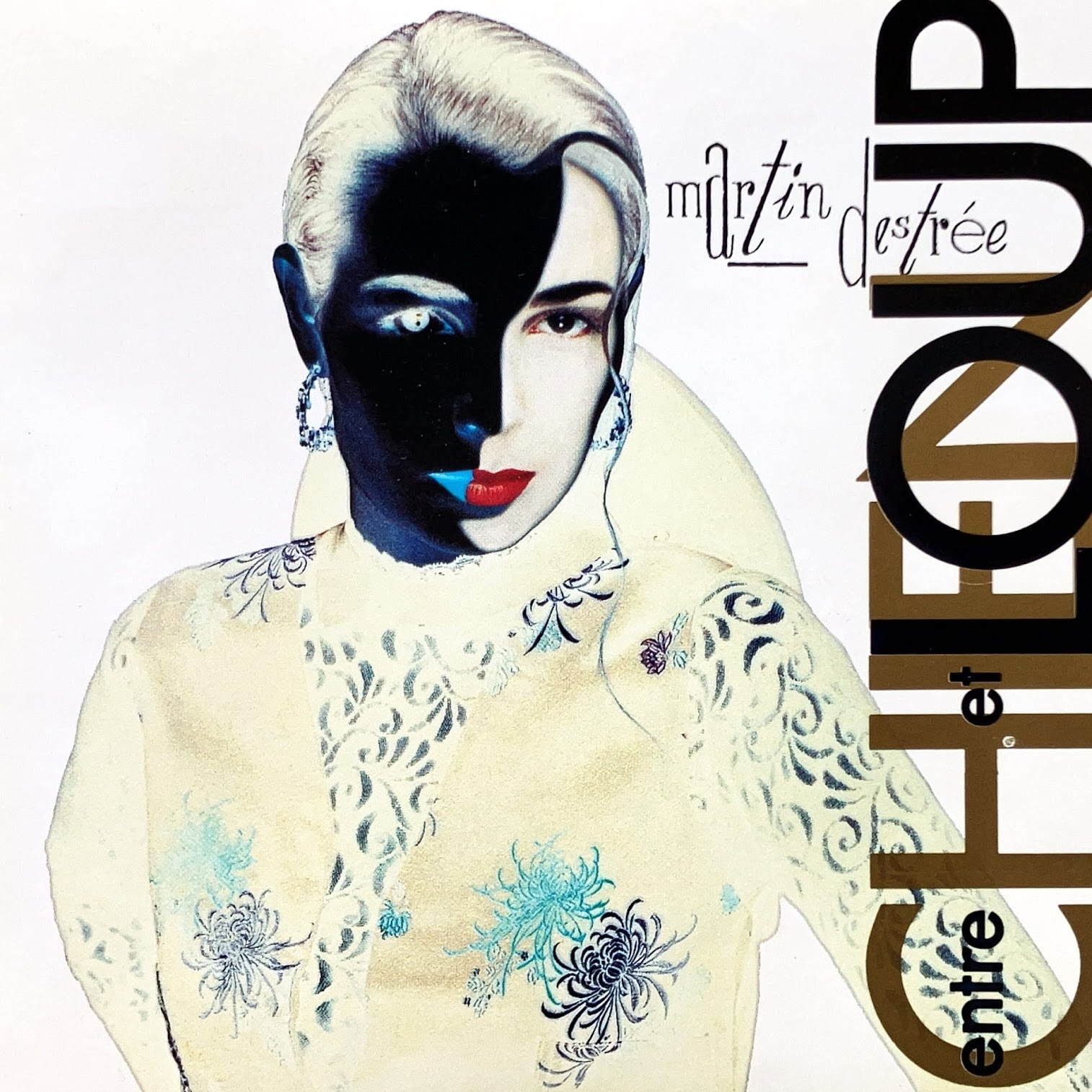

Photos were taken for the album and for its singles by iconic French photographer, Jean-Baptiste Mondino, depicting Martin in a stunning neo-Victorian wardrobe. Looking back, I believe Mr. Mondino captured the essence of Martin’s ideas on the record. Entre Chien Et Loup is full of songs touching on topics like genocide, patriarchy, racism, and on meditations on love and self. It’s an album trying to inspect centuries-long history of imposition and inquisition over women and the “other” by creating music that turns protest and resilience, personal.

Entre Chien Et Loup was introduced to the world via Martin’s first single, “Annabel Lee”. Hovering the worlds of art rock and jazz, Martin reimagined Edgar Allan Poe’s poetic muse as a different kind of heroine, one trying to find escape from a different kind of monstrosity. Through the mystery of its music video, the airs of its shifty balladry, and a bracing sense of lyricism, Martin’s song only hinted at the mercurial quality of the rest of the record. It felt like it was dangling the precipice right in front of its audience.

“Black Est Beau” would be the second single from Entre Chien Et Loup. Far from slotting into anything contemporary to its day, it tapped to a far more timeless sound – one rooted in African and American jazz music – to speak truth to a necessary antidote to the prevailing sense of growing French bigotry: an open embrace of multiculturalism. If Entre Chien Et Loup shared the spirit of Joni Mitchell’s Hejira, here’s where Martin was able to provide a needed corrective to some of the images gleaned from Joni’s *Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter*.

What keeps me reintroducing myself to Entre Chien Et Loup is the profound sense of grace and elegance in the music. In a world where there’s always a hurry to frontload songs with sonic gimmicks, there are still niches of space left for albums like these that gain their currency through stateliness.

You hear this sophistication in the opening track of Entre Chien Et Loup, “Dans La Lumière”, a song spiriting the album’s titular ideas. A gorgeous song driven by the full range of Martin’s rich, husky voice, “Dans La Lumière” moves (through music and lyricism) on motifs that inspire in-between feelings. Is this music Martin trying to affect nostalgia or to infer solemnity? It’s a clear picture one can depict showing Martin trying to express all those ties that bind us.

Visions of a fourth world start to crop up in my head when I hear the next track, “L’oiseau Tonnerre”. A song written as a call to arms to symbolize the subjugation of the Indigenous American, also functions as an environmental protest against “white flight”. The music itself hovers around so many influences it renders itself free to experiment and propose a new angle for its bedrock, jazz-rock.

“White Chapel”, similarly, takes inspiration from the story of Jack the Ripper by shifting focus back to the women who were unjustly killed by trying to survive in a world that lives off their broken souls. In her mutant funk, the victim-blaming is met with such shock as those murders. Entre Chien Et Loup, through and through, is an album that reveals itself as openly, unvarnished, feminist.

As a man, it’s that femine revelation of what we need to hear that gives power to Entre Chien Et Loup. In a woman’s voice, we find the universal voice of a song like “Au Clair Du Mystère”. An homage to Jean Cocteau’s film adaptation of Beauty and the Beast, it journeys true more to the dark undertows of the original hit fantasy, touching on how we – as multi-hued sexes – jump to certain prejudices and biases, at our peril. Through beautiful Balearic balladry, smoky, ambient jazz atmosphere, and some kind of luxurious meditation, Martin and friends guide us through a stately song asking us to return to an age of innocence.

“Le Cri Du Loup” shifts the album towards something else. Looking back, one can sense why Martin would turn towards continuing her career in sacred music. In powerful ways, a song like this functions as a self-examination of the perils of wanton religion while sussing out the powerful scripture of its singing tradition. Mary Magdalene, that Biblical cipher used to subjugate women as either hussies waiting to become repentant apostles, is placed by Martin as a solitary wolf trying to survive the hell of ever-increasing empires subjugating women as they blaze through land. In Martin’s jazz-folk chamber music, a night flight sounds like the high drama it is.

In an album full of masterful songwriting, its final three songs remain crowning visions for an artist that captured something truly special in a bottle. On the first song, “Torquemada”, the hideous conservatism of Tomás de Torquemada is transmuted towards all those who practice a certain kind of modern Inquisition that still seeks to impose out-dated beliefs. Martin saves her final circle of hell for those who remain silent, hiding behind faith and religion, when freedoms are put on the cross. “Torquemada” is a fiery, atmospheric jazz-rock number sung with the conviction of one whose journey to the truth found a maddening constant.

The fire of “Sortilège Moi” burns differently. On it, we get to hear Martin’s questioning of spiritual and human laws that impose morality on love that feels divine. Somewhere between heaven and hell is the magical connection that goes beyond faith and belief. It’s a powerful dance that is captured expertly in another soulful, atmospheric ballad that has all the hissing of Joni’s summer lawns.

The album ends on my favorite song, “Orage”, a prayer or meditation of sorts – at least that’s what Martin shared in liner notes. However, in reality, this hymn unfurls gorgeous mystery upon mystery of what it means to aspire for some kind of unexplainable heaven.

For those that believe, its harmonic mysticism details the everlasting gift given to those who can, wisely, peacefully, navigate past all of life’s many storms. For those that don’t, it’s a deep understanding of the responsibility of faith – in having belief in something tangible that can get you further than you think. In the end, what I still can’t understand is why such a powerful, prophetic, album, new theses nailed to the door of an ever-evolving flow of music, had few disciples…and even fewer apostles.

For the past year, I kept thinking: “How will I ever get around to writing about such an album?…to signal its arrival?”. In the end, it could be by leaving you all to spread the good word.

One response

Thank you for sharing this album! Martin’s voice and singing style conveys depth so effortlessly. It reminds me of David Sylvian’s voice in that way — coincidentally a gifted singer who also eventually rejected their pop music past.

If Martin truly stopped producing music (of this nature), then this album’s existence feels like a blessing.

Favorite tracks: L’oiseau Tonnerre & Black Est Beau