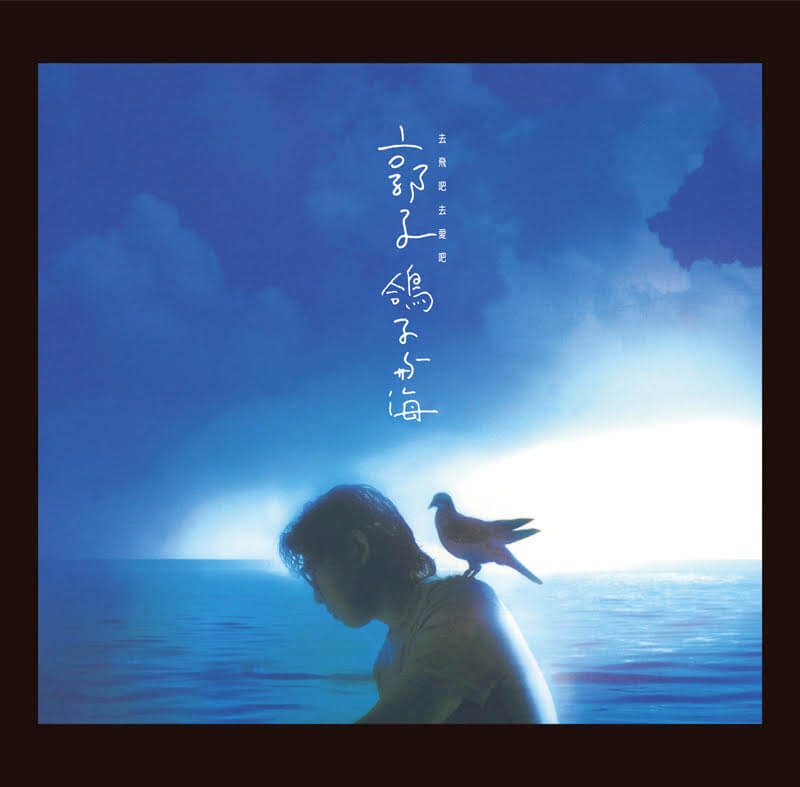

One of the great things about autumn is that it presents an opportunity to share music that’s a bit more ruminative, something that takes its time to reveal its true colors. I’m reminded of this as I revisit Kuo Heng Chi’s underappreciated but surprisingly prescient, contemporary-sounding music, particularly his 鸽子与海 (The Dove and the Sea).

In Taiwanese pop music, Kuo has always been something of an outlier. His entry into the arts came not through records, but through theater and acting. By the time Kuo reached the point of trying his hand at music, his interest gravitated toward a specific style of balladeering—one familiar to those who watch Taiwanese dramas.

Kuo’s singing embraces a style deeply indebted to Chinese folk balladry, which allowed him to explore ideas in his 1989 debut album, 純屬虛構, that melded traditional sounds with more contemporary Western vocal styles.

Listening to Kuo’s music, one can hear a voice that spans grand octaves and is steeped in emotion. Many Taiwanese listeners described the music supporting his voice as almost a soundtrack to his lyricism and phrasing. Despite critical praise for his debut and its 1991 follow-up, 兒童樂園, his audience never truly connected with what Kuo was aiming to achieve. By the early ‘90s, he transitioned from his solo career to a songwriting role, writing for Taiwanese pop stars like Tracy Huang, Jacky Cheung, and Faye Wong.

In 1991, while Kuo was taking a break from his singing career, an unexpected opportunity led him in a fascinating new direction. In a bold move, he created a cultural stir by leading a dramatic adaptation of David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, reimagined as The Diplomat’s Woman. In it, he performed semi-nude in “feminine” clothing, inhabiting a role originally written for a woman as a person of transgender. And to further advance this reimagining, for this production, Kuo took it upon himself to compose and perform an equally forward-thinking new soundtrack, resulting in the 1993 album, 外交官的女人 – 舞台劇原聲配樂. A stunning blend of influences: Japanese kabuki, Peking opera, ambient, and New Age music, executed in ways few understood or appreciated at the time.

Now freed from the demands of a major label, Kuo performed on his own terms.

In 1995, five years after his last solo work, Kuo set out to create the kind of music he truly wanted. Working with lyricist Xu Changde, who offered the words, “Dove, fly away! Love freely!” as inspiration, Kuo understood that 鸽子与海 (The Dove and the Sea) had to be pure and free from distractions. A sailing trip to Penghu, where he almost got lost at sea, seemed like a sign. From start to finish, Kuo created music that came from a new place.

Entirely self-produced and released on his Dong Da Music label in 1995, The Dove and the Sea presents the culmination of his search for a unique sound. The album opener, “旅程 (The Journey),” takes its time to unfold, with barely-there orchestration building toward a swelling pastoral, deeply yearning backdrop. Kuo’s graceful singing on this track, influenced by American gospel music, is impactful in its restraint.

The title track, “鴿子與海 (The Dove and the Sea),” is an atmospheric journey—a nearly six-minute arrangement shifting between melancholia and hope. Songs like “永遠美麗的寶島 (Forever Formosa)” blend Trip Hop’s rhythm with Taiwanese folk, showcasing his homeland’s sound. Tracks like the ethereal “瞬間與永遠 (Instant and Eternity)” strip down music to its essentials, letting Kuo’s delicate phrasing speak softly but with power. Is it jazz? Ambient? A new form of Taiwanese soul music? Or The Spirit Of Eden sprouting its influence on some distant shore? Whatever Kuo aimed for, it sounded like little else. The same goes for “把我的手握緊 (Hold My Hands).

For me, it’s intimate highlights like “兩心 (Two Hearts)” that keep me coming back. This duet with an unnamed female singer captures a gorgeous leitmotif reminiscent of Tats Lau’s Music from Autumn Moon, reimagined as a grand torch ballad. The phrase “still waters run deep” seems tailor-made for this record. Strings swell, and Kuo’s voice rises to meet their drama. One simply has to slow down to appreciate Kuo’s tempo. He once admitted that certain songs left him emotionally drained, sobbing on the floor.

Unafraid to tap into his past, even more uptempo “adult contemporary” tracks like “另一個天地 (A Different World)”, feature something that fits with the larger musical theme. Near the end of the album, a song like “藍雨衣 (A Blue Raincoat)”, tips its hat closer to the world Kuo was aiming for. Much like the late, great Leonard Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat”, these are new songs full of universal themes – those of love and hate – donning new clothes, asking you to sit down and wait a while (until they’re done dressing up).

In the end, trust me when I say: it takes time to work your way up.