There’s just something about Valentine’s Day that stirs me to share music steeped in that feeling. If you know me, you know I love “love songs.” I firmly believe that the hardest songs to write are those that touch on love (in its myriad meanings). It’s what led me this time around to cut to the quick and share Kohshin Satoh’s Arrston Volaju (アーストンボラージュ), an album immersed in that mercurial thing we call love.

Kohshin Satoh belongs to the new school of Japanese fashion design. Much like his contemporaries—the more widely known Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake—Kohshin arguably can stake his ground in transforming the art of crafting menswear.

Looking at his designs, it’s not hard to understand the appeal. Often featuring various textiles with different textures, each piece has a certain edge, clearly inspired by traditional Japanese wear—closer to what you might find on a battlefield or in a barracks worn by a samurai—than the more delicate, minimalist constructions inspired by ceremonial garb seen in the works of Miyake or Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons. If one tries to pinpoint where contemporary “Japanese streetwear” draws much of its influence, a significant portion, arguably, comes from the vision of someone like Kohshin Satoh.

It was in 1975 that Kohshin Satoh opened his first atelier and boutique in the Tokyo neighborhood of Omotesando—a storied area of Japanese high fashion. A native of Sendai, Kohshin used this outpost to plant his flag and, in a sense, escape the influence of his mentor, Issey Miyake, who had hired him after he graduated from the influential Bunka Fashion College.

Going by the name Arrston Volaju—a Japanese transliteration of “Aston Volage”—his design house’s decidedly askew, edgy silhouettes and designs quickly attracted influential clientele such as Miles Davis, with whom he became fast friends. Davis believed that Kohshin’s designs were decades ahead of their time. Whether on stage or in fashion shoots, Miles arguably introduced and championed Kohshin’s work to a much wider audience by dressing exclusively in Arrston Volaju, signaling a shift in both his personal visual representation and the direction of Japanese fashion.

By the mid-’80s, Kohshin’s ideas—alongside those of Kenzō Takada, Kansai Yamamoto, and Junya Watanabe—were breaking away from the French school of fashion design and popularizing a distinctly Japanese aesthetic, loosely dubbed “Hiroshima Chic” by dismissive critics. By 1985, his innovations had become influential enough to earn him the Mainichi Fashion Grand Prix—Japan’s most prestigious fashion design award—thanks to his exploration of more existential, “Third Skin” concepts.

Although less known today than some of his contemporaries, Kohshin’s clothing would become a hidden gem for artists as diverse as David Bowie and Michael Jackson. In the late ‘80s, he was hobnobbing in New York City with luminaries such as Andy Warhol (who would don his wares) and helming fashion shows that spotlighted a global underground dance scene.

It is on the catwalk that you can see why, in 1990, Kohshin Satoh turned his critical eye toward the world of music. Unlike most staid fashion designers of the ‘80s, he frequently invited DJs and musicians to perform on stage. In an age when house and techno were largely confined to the underground arts scene, Kohshin often used house music to soundtrack his shows.

It’s no wonder that in 1990, Kohshin ventured into music as both a musician and a producer. He signed with Teichiku’s fledgling dance-centered record label, Danceteria—named after the famed NYC club of the same name—and collaborated with a veritable murderer’s row of producers and remixers, including Eric Kupper (of C+C Music Factory fame), Mark Kamins (who famously worked with Larry Levan, Madonna, and the Tom Tom Club), the enigmatic Stephon Drake McQueen, and a Japanese remix crew known as Mixs International DJ – MASTER MIX PROJECT (or M.I.D. for short) to launch his own house-centered debut.

Looking back at the tracks from Arrston Volaju (アーストンボラージュ), one senses Kohshin’s deep love for the influence of American culture in both his design and his music. Much like Haruomi Hosono’s “Come★Back” — itself a love letter to American hip-hop — songs like “Say You Love Me (In The Clouds)” attempt to infuse the Japanese experience into what was then a deeply American house sound. Over ballroom (vogue)-ready beats, Kohshin delivers a speak-rap in Japanese—a plea for love—then switches to English as he floats above the muscular, angular construction of that gorgeous house beat. In musical form, it is exactly Kohshin’s design aesthetic recontextualized.

Here’s where I wish I had more to share about Arrston Volaju’s unheralded co-creator, Stephon Drake McQueen. It is Stephon who revisits and deconstructs John Coltrane’s urbane take on love — his A Love Supreme — transforming it into a “Higher Love,” a longing house ballad that meets Kohshin’s emotional palette on equal terms. Spread over three tracks that dissect “the things we do for love,” his meditation ends the album with that ever-present edge found in Kohshin’s sartorial choices.

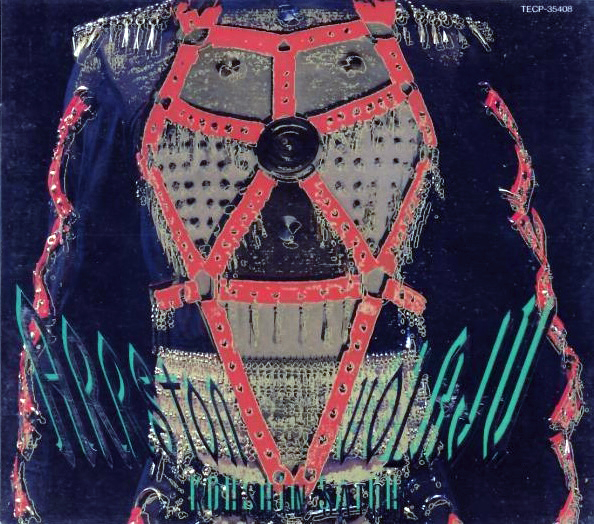

Looking at the cover adorning this album, I can sense what Kohshin was trying to capture. It harkens back to Satoh’s concept of the “Third Skin”—a challenge to the notion that clothing is merely practical or decorative. Instead, it positions fashion (and what you wear) as a philosophical tool—a means to explore identity, protect the psyche, and connect with the intangible.

In that same year, the design gracing this cover would appear on Kohshin Satoh’s “Crucifixion” Collection. In that line, garments incorporated cross motifs and bondage-inspired straps, symbolizing the tension between physical constraints and spiritual liberation. What we wear can indeed express what we feel. And in this other form of Arrston Volaju, where Kohshin is more palpably heard on the dancefloor, we can sense what he felt at that moment of inspiration. It’s that highest love—derived from peace and unity—which, yes, sometimes requires sacrifice and meditation on. And what exactly that is? That remains the eternal question.