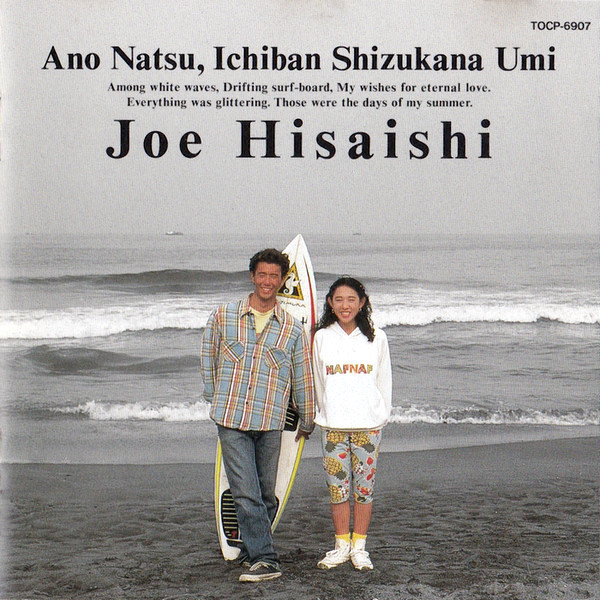

Fall is something else, isn’t it? As beautiful as the season is – simply one look outside can affirm this – there’s always something in our communal, lived-in experience that’s tinged with a certain longing and/or nostalgia. Perhaps, it’s a certain realization that nothing is permanent and everything pertinent has an end. With this thought in mind, it’s fitting that when iconic Japanese actor/director Takeshi Kitano looked for a composer to give musical life to a film that just permeates with such moments of quiet meditation, he turned toward Joe Hisaishi to soundtrack A Scene at the Sea (あの夏、いちばん静かな海。, Ano natsu, ichiban shizukana umi — which you can listen to in full YouTube mode, here, on the aptly named Dream Resort channel — editor’s note.

What was it? Nearly 5 or 6 years ago, when I first wrote about Joe. In that snapshot in time, Joe was finding his footing as a minimalist musician who was transitioning into a pop artist. It was a few beats before this once turned ethno-fusion band member (with the Mkwaju Ensemble), then contemporary maximalist anime soundtracker, who’d become the in-demand composer for myriad Miyazaki-helmed productions was at a crossroads. It was then he had taken the right fork in the road.

So, much like one of his huge influences, Quincy Jones, Joe had discovered how to tackle all sorts of musical styles and tonalities in a way that was becoming singular to him. However, few knew at that moment what to expect of the man he chose to work with, Takeshi Kitano.

Takeshi had always been mercurial. Growing up in one of Tokyo’s more hard-nosed neighborhoods, from a young age Takeshi was intrigued by the more-frowned upon characters of society. He knew the people who carried knives and resorted to hustling to survive. It’s that school of life that spur him to abscond from a career in engineering and pursue a career in comedy, one that would propel him in the span of a few decades to become one Japan’s most known comics and TV personalities.

It wouldn’t be until 1988 when Takeshi, who had notoriety mostly through comedic roles, began to take the brave step to fully take a serious role in a movie (Violent Cop) and in doing mark a turning point in his own career. Only once before, appearing with David Bowie and Ryuichi Sakamoto in the 1984 movie Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was Takeshi able to show this other side of his acting chops. When Violent Cop lost its original director he took it upon himself to finish the movie and direct it himself, as well. Its success and original voice would then allow Takeshi to pursue more of his cinematic vision.

Just a year later, Takeshi would continue exploring the darker side of Japanese society with 1990’s yakuza revenge drama, Boiling Point. Although that movie would cement Takeshi as this new auteur of Japanese cinema, Takeshi felt restless. His next movie would show various sides few expected from him.

For his next film, Takeshi wanted to explore something (seemingly) far more simple, an archetypal teen romance. In his head he’d want to write like a bizarro, Summer of ‘42. あの夏、いちばん静かな海 (A Scene At The Sea) would become this story, one he wrote detailing the love affair among two deaf mute teenagers, the sea, and surfing. Unlike his previous movie, he knew this movie would only work if music could do the heavy lifting and portraying and amplifying things that were simply unsaid. Deaf people could not hear the pink noise of the sea – for them its beauty was deeper (in a different way). Adopting a visual aesthetic of grays and blues, the images of the film in his mind were driving him to tell such a story, best he could.

This film would mark the beginning of a long string of more “adult-themed” movies Joe would soundtrack for Takeshi. A huge part of the reason would be that Takeshi valued putting the music written for his movie on equal footing with the moving image. And in this film, Joe was spurred to explore a specific time of the year – that time in late October – when the biggest waves are those few look to ride, and when the coldness of the season marks a temporal change. Fittingly at that moment in a Satie mood — with Fairlight sampler prepped in “Camilla” mode — Joe jumped at the chance to retap into that more minimal, less orchestrated, impressionistic side of his. In the end, they can sense their two points of views could work together.

Through the wonder of YouTube, you can view the film yourself and realize just how important and forward-thinking the collaboration came to fruit. Viewing that film, and realizing how something as simple as finding a surfboard can change the life of the film’s protagonist, is something that bubbles up in Joe’s music cutting through Takeshi’s quiet, atmospheric, film. Rather than make the beach this vibrant, luxurious thing, it was this imperfect place, perhaps like us, that had a grandeur in spite of it, just like us. Takeshi would share image stills of certain filmed scenes and give Joe the freedom to create the music Joe felt was appropriate.

Aided by the wonderful work of guitarist Hiroki Miyano, violinist Masatsugu Shinozaki, vocalist Junko Hirotani (since deceased) with Masami Horisawa on bass and Makoto Saito on cello, Joe created this deep, deep, deep, autumnal groove music couched with moments of struggle, perseverance, love, and loss. What those who couldn’t read sign language, or pick up on via inner non-verbal cues from the film’s two romantic leads, in key moments, were implied by themes from compositions like “Silent Love” and the “Clifside Waltz” painting for us the fuller picture. Simply put, this movie would not be the same without Joe’s music.

And like anyone that has since the movie can relate, it’s its final scene where just Joe and Takeshi were capable of conjuring such art that undoubtedly lingers with you the most. Without revealing too much, it’s a solo journey we all must take eventually “out to sea” (but one that sounds ever more profound with such a sound tracking it).