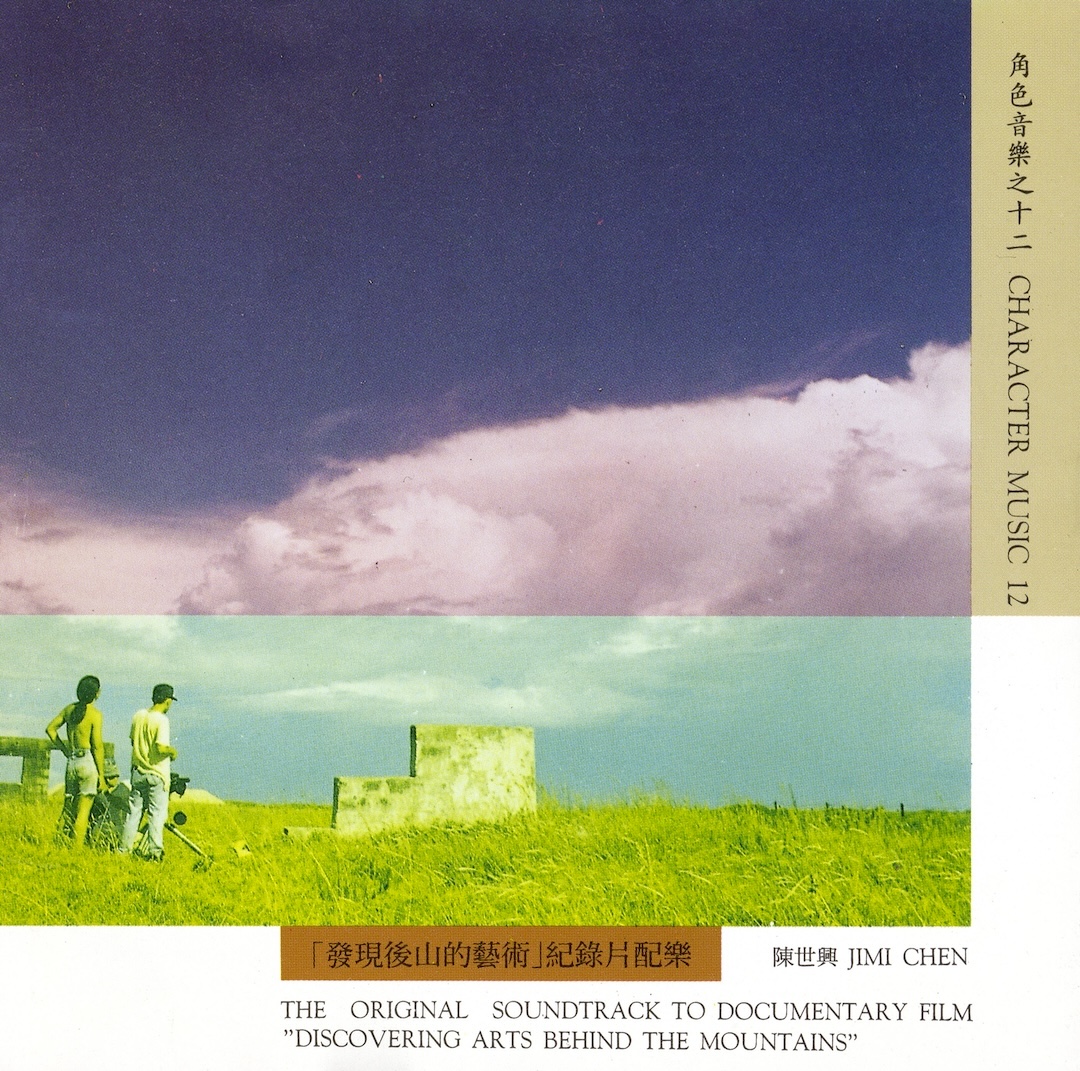

The chirp of crickets, a babbling brook, the melodies of a songbird, certain things trigger a sense of new life or of spring settling in. I say this because I feel the same way about Jimi Chen’s Discovering Arts Behind The Mountains 發現後山的藝術, his “character music” soundtrack for a documentary of the same name (which you can also find here). Using synthesized tones and meditative tonal melodies, it’s his Taiwanese ambient soundtrack (I think) cuts closest to recreating a certain environmental atmosphere through music.

Born in 1959, in the outskirts of Taipei, Taiwan, where Chen Shixing’s (Chen Shyh-Shing) journey to music came not through any learned school or training but through expressing himself outward from his first love: guitar.

By all accounts, it appears that Jimi has always been one to shy away from the limelight, preferring to let his music do the talking. Early stints in various Taiwanese rock bands led him down the road to music composition – composing, mostly, for other pop and rock bands. However, while studying architecture in university, his other love – that of literature – led him to fall hard for the more meditative works of writers like Camus, Kafka, and Nietzsche. It’s this thirst to comprehend that led him to seek the indescribable, pushing himself to separate from the commercial music scene.

It was in the mid ‘80s, during a period of deep contemplation that Jimi discovered the music of Brian Eno. Far different from the mannered classical pastorales or the cold avant-garde he heard in school, or the maudlin melodies of Taiwanese ballads, it presented a new third way to express the “landscapes of the mind”, per se. That ambient minimalism had the sound of music he had been looking for.

Living a more monastic life, which stretched into veganism and meditation practice, Jimi invested most of the money he had earned writing for pop musicians into creating a record studio for himself near or in the mountains. Some of his first commissioned work, under this new musical vision, was done for free for contemporary Taiwanese dance troupes hungry for distinctly modern Taiwanese music that didn’t fit a traditional mold. Overlooking green expanses, once he started to work on his first few records, we would be treated to a pioneering vision.

Jimi signed to Taiwan’s Prime Records (鍾石唱片), christening a new label trying to breakthrough Taiwanese artists looking to create more atmospheric/ambient music to foster a “New Chinese Music” that drew from New Age and “new music” styles. In the span of a year, like manna coming down from the heavens, Jimi poured out four different albums – 空 (Emptiness), 山 (Mountain), 靈 (Spirit), and 雨 (Rain) – that found him being likened as Taiwan’s answer to Kitaro.

Driven by a deep reverence for nature, Chen’s compositions then would often echo the tranquility of the natural world, inviting listeners to spirit in some introspection and contemplation. Although it would take him five years until his next “official” release, it appears that wait was well-worth it.

In 1993, Jimi was invited by a new Taiwanese indie label, Crystal Records, to take on a new challenge: compose music for film and theater. This so-called “Character Music” moved him away from the symbolism of creating music for nature and into the abstract world of music for ideas and themes.

For those that care to understand what these soundtracks were about, this is what I think they stood for:

The Character Music series (numbering 12 in total, from I can tell) captured a diverse array of musical ideas, from the tranquil simplicity of the first release, “Character 什麼角色,” featuring instrumental works from acclaimed films and documentaries, to a blend of traditional and electronic elements in it’s next release Jim Shum’s “的電影音樂 (Music For Films),” and Chen Ming-Chang’s electro-acoustic “戲夢人生 (In The Hands Of A Puppet Master)” the series, from the beginning, showcased the evolution of Taiwanese ambient music since Jimi’s totemic release.

The challenge, of course, was for Jimi to not just play catch-up to all the cutting-edge avant-garde music new Taiwainese artists were releasing but to create something new that others simply couldn’t copy. It’s why I think Jimi’s contributions to the series are its most impressive.

On what looks like it became the final entry, Discovering Arts Behind The Mountains 發現後山的藝術, Jimi was tasked to create music that spoke to all the art adorning the records in the series. Far from painted by European or Western artists, it’s those artists from the “supposed” backwaters of Hualien City that had created those intriguing abstracts (inspired by indigenous ideas). A documentary was filmed to promote the work and artist, and Jimi (who had already recorded music of the indigenous people there) seemed like a no-brainer to enlist as composer.

In the beginning, in 1993, the original thought – at least for the producers – was for Jimi to edit all the field recordings he had of the area into a soundtrack. Jimi had other ideas.

As Jiimi recalled in the liner notes:

“Some states of mind are difficult to explain, and what can be grasped during the creative process is often just a momentary emergence of such states. To recount the emergence of those states of mind during the creative process, I prefer [to recall the most important process] which is a stillness, a quietness where, after calming down, one can delve deeper, and also leap, transcend. The moment I want to emphasize is one of non-attachment, gaining almost complete understanding in a short time; under that light, people become silent, not wanting to say much more, but capturing the emerging states of mind, letting them flow out with the notes, leaving them in the form of music.”

Simply put: he had original music better suited to recreate those portraits.

Discovering Arts Behind The Mountains 發現後山的藝術 is just as simply, the culmination of his life’s work. Opening track, “Goodnight Valley Main Theme / 晚安山谷 (發現後山主題曲)”, creates some floating idea of environmental music where Jimi’s synthesized tones hit the uncanny valley of organic creation and melodic evolution. Distant echoes of “temple music” filter through a prism of ambiance, coming in as haunting textures to move this minimal take on Eno’s “discreet music”. It’s songs like “Swim / 游泳” that recall that spirit.

The percussive dance of “Up Mountain / 上山” instantly conjures the more abstract feeling of trying to propel yourself through elevation. Other songs like “Cutting Edge / 切割邊緣” carve out their connection with the abstract works, just as vividly. What’s fascinating about Jimi’s work here is just how much percussion – a mainstay mover of S.E. Asian music – does the heavy lifting to float the music.

It’s the propulsion of wayward drum machines and hammered tones that paint the joyful world of songs like “Behind The Mountains / 後山”. The piano is transmogrified back to its percussive role on the spectral sound of “Memory, Unsaid / 沉默回憶” coloring the breath of guttural tones.

And when Jimi aims for ever more meditative moods, on songs like “Heart Unhold I+II / 心無住 I+II”, the clear shepherd tones he’s able to muster from his keyboards are crystalline in their clarity. As I hear Jimi’s “In The Woods / 在林中” and the rest of the record, I keep hearing a connection to pastoral works like Sowiesoso from Cluster. One can evoke the organic simply by making a connection with tonal things that others can latch onto.

The mountain isn’t really a mountain. The valley isn’t down below. You can see the forest from the trees. It’s not how you picture something but how it pictures you. As I’m hearing the final track of this record, “Valley / 山谷”, I can conjure a vision I’ve never seen – as it’s a picture painted quite vividly (through sound + music) by a true genius at creating landscapes with music. It’s a wonder, realized: true character music.