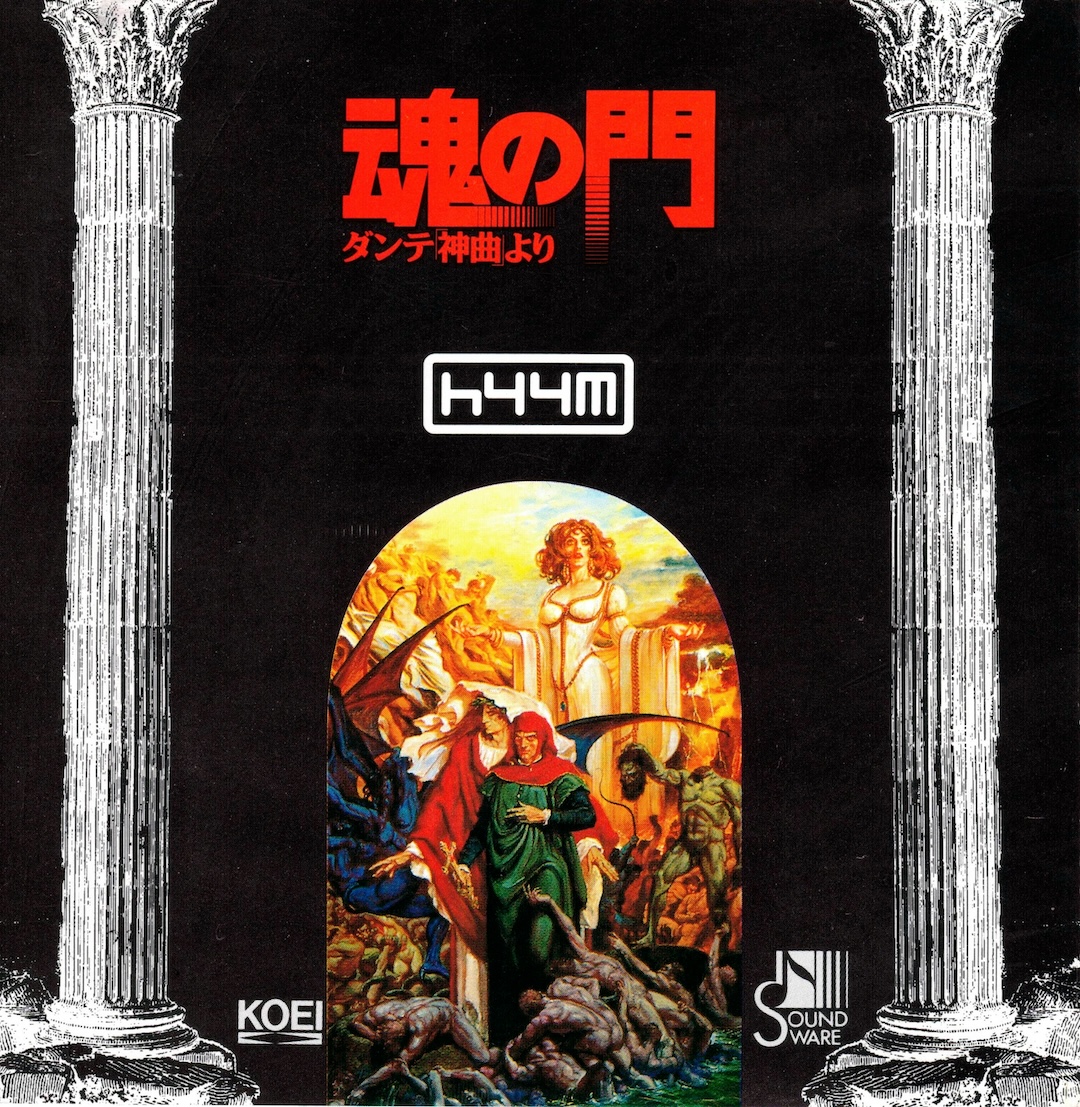

First off: a huge tip of my hat to fellow F/S blog reader, Victor Hsu Jui-Ting, for cluing me to today’s album a good while ago. If you know me, you know that video games, anime, and manga are some of the artforms I’m the least versed about and a lot of quality anything is there. It’s something that sort of pains me to admit, as it’s where the more I dig around, the more I am pleasantly surprised at what I discover hidden in plain sight. And I say this, because it’s in one of those realms, that of video games, that such an album like hyym’s 魂の門~ダンテ「神曲」より (Tamashii no Mon ~ Dante “Shinkyoku” Yori) could only exist.

Raise your hand if you ever had the pleasure of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy? For those that haven’t, I’ll spare you a Wikipedia read-through and summarize it, best I can, as this:

The Divine Comedy was a medieval Italian epic poem written between 1308 and 1321, consisting of three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. It followed the poet Dante (playing himself?!) as he journeys through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil; through Purgatory, guided by Virgil and Beatrice (his idealized love); and finally through Heaven, guided by Beatrice. Throughout the journey, Dante encounters various historical and mythological figures, as well as contemporary people, each representing different aspects of human nature, sin, and virtue.

In essence, it was 14,233 lines of poetry reflecting on divine justice, redemption, and the afterlife, offering a vision, a journey of course, of one’s soul towards God. Most of what we know as classical art would conjure its views of hell and hell, love and retribution, due in large part to Dante’s vivid imagery on this literary work.

Now, imagine that “in the year of our Lord”, 1992, a video game publisher decided: “You know what needs to be made into an action/adventure game (with light RPG elements)? That first bit of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedia.”

Of all the unlikely things that could exist in our world, Japan’s Koei Co., Ltd. probably contributed to creating a whole bunch of these in the video game side of the equation. Headquartered in Yokohama, Japan, Koei originally began their operations in the early ‘80s as a company more interested in creating software for the PC and business computer market. The meteoric rise of the PC side of the equation, led by Japanese brands like NEC, Fujitsu and Sharp, forced their hand into transitioning into the more lucrative/riskier ventures and into the world of video game publishing.

Koei would come into a world where the only way to gain any kind of market share would be to carve out your own niche. Unlike video game publishers tied to the more “conservative”, family-friendly standards of Sega, Atari, and (famously) Nintendo, Koei operated in that gray zone afforded to video game publishers who created content for PC-based gamers.

In the beginning, Koei would make their mark by creating adult-oriented RPG (role-playing games) like Danchi-zuma no Yuuwaku (団地妻の誘惑), that fed the appetites of sex-starved dating sim gamers. It was off the successful back of their “eroge” software that Koei would branch out into what would truly become their calling card: history-based games.

Whether on an MSX console or on any kind of IBM PC clone, stepping inside a ‘80s or ‘90s Japanese, you’d be hard-pressed to not find a Koei branded historical-based video game series. From Romance Of The Three Kingdoms (三國志) based on Luo Guanzhong’s classic Chinese novel to Nobunaga’s Ambition (信長の野望) based on Japan’s Sengoku period, Koei’s specialty was taking apart a historical happening and making some kind of game out of it.

And for all their serious games, Koei still dabbled in unlikely hit games like their Top Management トップマネジメント (everyone’s favorite: a business simulator…) and Aerobiz (エアーマネジメント 大空に賭ける), a flight…tycoon…simulator. In the wide world of video game publishing Koei found their market. It’s what brings us back to hyym’s 魂の門~ダンテ「神曲」より (Tamashii no Mon ~ Dante “Shinkyoku” Yori). It was in 1992, when the Japanese video game market, unlike elsewhere, was dominated by two players: Nintendo and NEC.

Unlike Nintendo, NEC tapped into a video game bracket that was decidedly more price-conscious and risk-averse. In an age where consumers could find an SNES, a 16-bit gaming console, at a big-box store for around $199 (or $398 in our time), they could also find for $2400 (our adjusted-for-inflation price) a PC-9800 from NEC that could function both as a high-end 16- or 32- bit gaming system and also a user-upgradeable, personal computer that could easily wallop an Apple Macintosh Classic or any other graphic-intensive foreign IBM PC clone and handle Japanese-language typed characters. The promise for users was that with its built-in high-end (for its time) graphics card, FM sound chips, and newly available CD-ROM drives, they would find a plethora of games and gaming publishers ready to create software for it.

Unlike Nintendo, NEC users would find out that video game publishers flock to where the consumers are. So, as gamers on a Game Boy had it easy to find and play stuff like Kirby’s Dream Land or Street Fighter II for the SNES, NEC gamers had to settle for a much smaller selection that could work with the computer keyboard limitation of a PC-9800 system. It’s this market where users had now been conditioned to sit at home or an internet cafe to play RPGs and sims of all sorts (from erotic to neurotic), for hours on end, that made it easy for Koei to justify giving a green light to a game based on Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Watching gameplay of the NEC software, 魂の門~ダンテ「神曲」より, one gets a sense of just what it took to pull of the idea, visually. Visually, its pale, purple-ish, gray-ish palette genuinely captures the classical, Greco-Roman era vibes of its aesthetic influence, giving a stately, statuesque quality to a decidedly graphics-limited 16-bit visual display palette. However, sonically, that’s where you sense something just as interesting. Hovering in between two worlds – that of Italian opera-style operatics or ornate neoclassical melodicism and forward-thinking (for its time) techno and house music – even in its original FM-chip based playback, there’s something fascinatingly intriguing and all-around engaging about its soundtrack. And thankfully, for us, Koei did something special to promote and accompany the original release of this video game.

In an era when gamers still would go to an actual store to buy soundtracks to anime, manga, and yes, video games, Koei decided to release an “arranged” version of “The Gate of Souls” solely on compact disc media. What better way to add some value to newly available PC-9800 CD drive bays?

Some of you, I imagine, have run into “arranged” video game soundtracks. At worst, they’re just recreations where straight MIDI tracks have been fed to a soundcard and fed to a digital master or worse: orchestral versions that sap out any life to the music by infecting it with a Final Fantasy-fied version of the OG soundtrack. 魂の門~ダンテ「神曲」より (Tamashii no Mon ~ Dante “Shinkyoku” Yori) would be different.

Original sound designers for the game (Fiori Wakakuwa, Yoshiyuki Ito, and Masumi Ito) were given freedom to recreate and reimagine the music and they’d do so by reconstructing it as a one-off band they’d dub, “hyym”. Under hyym, they’d invite singer, Nami Sagara, to add a certain kind of diva-quality – one of the archetypal, ancient type – to the proceedings, adding operatic theatrically to their music. As a group, the influence of the burgeoning IDM scene sprung roots in the musicality of their arrangements. Somehow, the guiding light for this soundtrack would be to create what would be a kind of “Renaissance house” music.

You hear hyym’s idea of “Renaissance house” in the first minute of album opener, “第一曲: 神曲ルネサンス(Divine Comedy Renaissance)”. Deconstructing the decadence of Donna Summer’s disco classic “I Feel Love”, they mutate its Teutonic Middle Age underpinnings into something probing for a different territory. Here one can imagine how Dante’s journey to the underworld is a journey into darkness.

Between the heavy grooves of “第二曲: 暗闇の森 (Dark Forest)” there is a mingle of unplaceable sampled chorale singing and operatic melisma that’s positively otherworldly when mixed with contemporary sounds we’re more accustomed hearing in of our day. On the track the follows, “第三曲: 賢人の丘 (Wise Man’s Hill)”, ambient house music that could easily fall into the trap of a Deep Forest, wisely remains in the awe of the mystery of its ambiance. You have tracks like “第七曲: テクノ・トルバドゥール (Techno Troubadour)” that add better bounce to the rococo styles of the Baroque and neo-romantics without sacrificing the tone and color of those eras. And on tracks like “第十曲: ブルートの崖~スティージュの沼 (Pluto’s Cliff ~ The Styx)” throbbing minimalism of contemporary music gets subverted and immersed in the deep histrionics of hip-hop, birthing or predicting something positively contemporary-sounding.

As I’ve already gone far too long writing about this album, I urge you to discover all sorts of gems hidden within the music. Can you hear how the music follows the journey of the protagonist? Can you hear how on certain points in the album Yoshiyuki Ito and Masumi Ito join in on vocals to give the music a hymnal quality? Sacred music that’s as divine or “divined into” as any. In the end, hyym, on songs like on “魂の門~ダンテ「神曲」より (Tamashii no Mon ~ Dante “Shinkyoku” Yori)” share as parallel a path to that journeyed by American house music, finding their influence in the polyphony of influences from an older Old World, exercising out all sorts of ghosts through all sorts of machines.

Sacred or profane? Haunting or bangin’? That judgement about this album belongs to someone else.