Rioting, looting, civil disobedience, and protest — nothing is born out nothing, all are born from a vacuum. When those we exploit say: “enough is enough” we need to stop and listen. If you think this story is something new, where were you the last 400 years? If you think the story is singular, you don’t have to dig very deep to see it repeating elsewhere, everywhere. Until the ending changes, people have to give voice to those unheard in its telling. Need an example? Hugh Masekela’s Techno-Bush.

It was nearly 4 decades ago that this South African icon of jazz music, Hugh Masekela, decamped to neighboring Botswana and started the unenviable task of remaining creative while his homeland burned through its best through the hands of state-sponsored death squads. The youth of South Africa felt stranded by a government more interested handing out corporal punishment than providing a society where they could create peacefully. Hugh would have none of that.

Gone was the promise of a future “Grazing In The Grass” or the “freedom sounds” of Hugh’s Afro-centric ‘70s creative horizons. He had achieved a global popularity unheard of by African standards but would show up back home in Johannesburg and be treated (or better yet, mistreated) just like any other black South African. Tired of self-imposed exile in Ghana he reluctantly headed home. For Hugh’s next album, Techno-Bush, there was some hope. Once again he found something in the little-tolerated and rarely played-on-the-radio but much loved music of the township: mbaqanga.

Highly rhythmic and complex, mbaqanga was unlike the steady “Western”-influenced music coming out of discos. Mbaqanga skittered and evolved, it was music Hugh realized could speak to a younger generation who were starving for home-grown influential experimentation.

Setting up a mobile studio of sorts dubbed in Botswana’s border capital, Gaborone, this Battery Mobile Studio could be a base others could use to cross all sorts of boundaries, behind apartheid. Aided with the help of Jive Records’s Clive Davis they’d outfit it with world-class instruments and equipment, where the hope was that once Hugh showed its potential, others could run with it at a low-cost price point and create music outside the thumb of the National Party’s censorship.

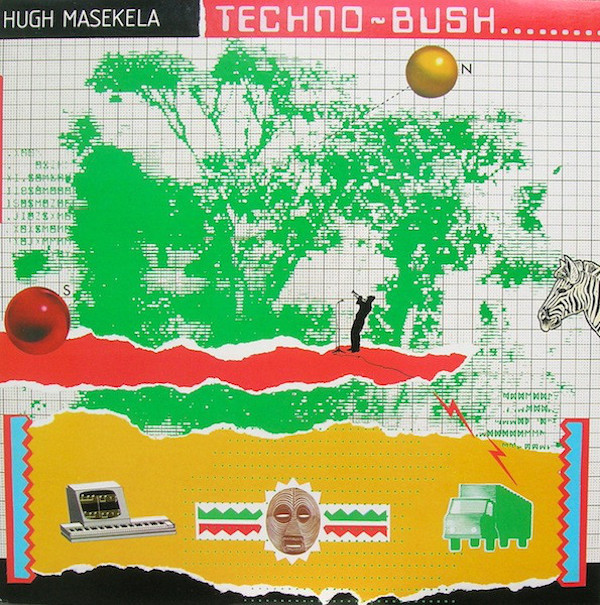

Joining him would be members of South Africa’s influential Medu Art Ensemble, a collective of artists who used pop art to express protest and promote a new kind of African-led Afro-Futurism, hip-hop had shown him one of those ways. Creating dance music as rebellion, Hugh would play to them demos of songs like “Don’t Go Lose It Baby” and “Motlalepula (The Rainmaker)”. Conjuring up vivid imagined vistas of a new Africa, their “techno-bush” became his Techno-Bush where the engaging music of the township could travel electric waves and come out as this new way that can promote a South Africa beyond colonial influence, create another world just using Fairlights, talking drums, and reeds.

Try as they could, the NP could not stop barn-burners like “Don’t Go Lose It Baby” and “Pula Ea Na (It’s Raining)” from becoming dancefloor hits everywhere and there. Ceding a good deal of his own album to engrossing electronic grooves, Hugh would draw you in and lob horn parts that spoke of an understanding he had with its original audience. Lyrics would secretly connect this new movement to an existing one that never gave up hope.

Even as secret police hunted and tore down this studio in 1987, Hugh’s music had gotten exactly to where it had to go. He found his “Graceland” and he’d be the one whose “Bring Him Back Home” would serenade that other revolutionary to the new beginning. You know it: a song and dance as old as time.