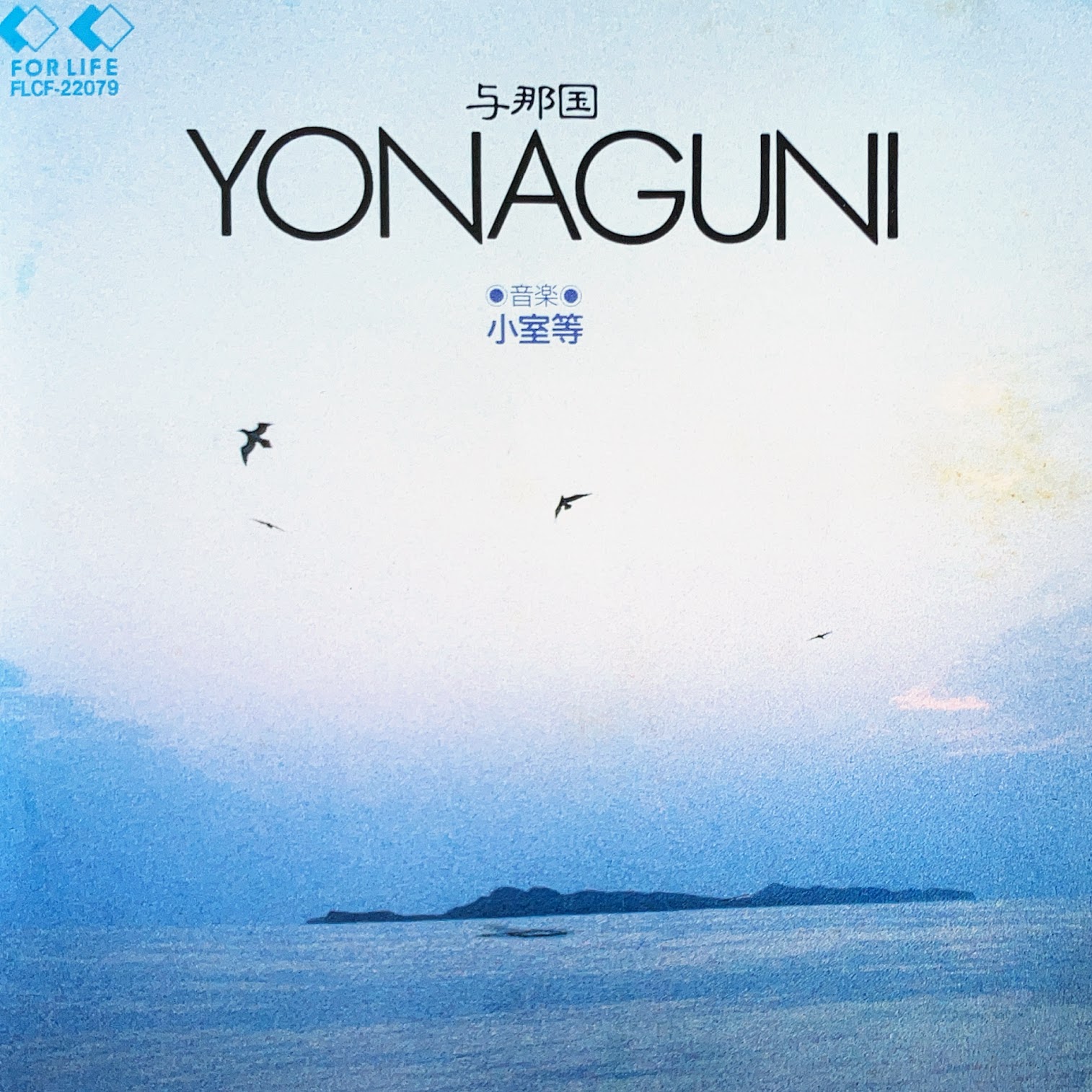

It’s late summer again. Like before, I’m drawn to music that evokes feelings found at the corners of each such season. And in today’s case, it’s that pull of the sea (or a life aquatic) that reminds us that life keeps moving, as much as we keep exiting, stage left. It’s something you hear in Hitoshi Komuro’s gorgeous, languid, ambient soundtrack, YONAGUNI 与那国, to John Junkerman’s “Uminchu: The Old Man and the East China Sea” documentary, released in 1990.

“Take a good rest, small bird,” he said. “Then go in and take your chance like any man or bird or fish.”

– Ernest Hemingway, from The Old Man and The Sea

Ever since the dawn of time, some of the most interesting stories, I think, are those that happen far from “civilization”, at the beginning of some kind of raw wilderness. Whether out in the desert, deep in the forest, amongst the stars of the universe, or alone in the vast watery expanses of our world, it’s our interaction with solitude, perseverance, and (eventual) finite presence, that draws out just what kind of humanity we’re capable of.

It’s what I imagine drew Milwaukee’s own, John Junkerman, to reorient Mr. Hemingway’s poignant tale of hope, “The Old Man and The Sea”, out of Cuba, somewhere else, not just parallel, in latitude and/or spirit. Somewhere, out at the far west end of Japan, in Yonaguni, Okinawa, in between the waters of the East China Sea and the Pacific Ocean, where the life of one, Shigeru Itoko, an 82 year-old fisherman, could present some other kind of story.

For two years, Mr. Junkerman, took to the sea with Shigeru, detailing the life of one of the few remaining “traditional” Okinawan fishermen. It’s aboard Shigeru’s skiffle, we’d get to see him trying to compete in stamina, viability, and ingenuity, with younger fishermen and their modern boats, to catch 400-pound marlins out at sea. Without spoiling too much, Shigeru’s tale would end there, where so much acquired wisdom could only match so much of the awesome strength of nature itself competing against us. Yet, Shigeru’s whole life joy was found when coexisting with nature.

Trying to honor that spirit was what forced Hitoshi Komuro’s hand. As a young folk singer, Hitoshi, came to prominence in the ‘70s when a new folk boom had brought the protest and introspection of the times to a culture unaccustomed to explicitly stating what they were feeling. Through albums like his iconic, 東京 (Tokyo), or his folk-rock group, 六文銭 (Rokumonsen), a through line existed of trying to actualize folk music for younger audiences. However, by the late ‘80s, it appeared all those days of wine and roses were past him. Now, as an older man, he too felt that (perhaps) that form he already explored could not speak to what he was tasked, at hand.

So, as Hitoshi viewed early screeners of the documentary, to orient himself to the scenes he had to soundtrack, Hitoshi felt something was off. To be true to the spirit of Shigeru, Hitoshi had to be in the presence of that same land and of Yonaguni itself.

Hitoshi would visit Yonaguni-cho twice. The first time, he spent days at the Kubura fishing port getting a feel of the environment, feeling the dry sea wind, seeing the soft pink light off the horizon, viewing tuna offloaded by the meter-load, fresh from the sea. Observing the men and women toiling away, he felt the movement of its people. In some way, going beyond what he saw on film, to actually experience Yonaguni itself, Hitoshi felt born again (in some way), he had songs in his head to sing now, but he couldn’t sing them. All of his lived-in experience couldn’t speak to this new knowledge.

When Hitoshi came back from Yonaguni to record the music for the documentary, all he could impart to his collaborators, Motohiko Satoh and Akira Sakata, were those esoteric inferences and influences of the locale. It’s what you hear on this album — a translation of what couldn’t properly be spoken of — in melodies, ambiance, and musicality, speaking truth to Shigeru’s microcosmic macrocosmic world. A bold chance, taken after a much needed moment of rest.

NOTES FROM Hitoshi Komuro

During filming, I visited Yonaguni twice and expanded upon the image I had in my mind. Or rather, I grew to like it even more.

At that time, I felt that the music was “born” again. The feeling of “being born” happened twice. Yet, when I tried to create the music, I couldn’t do it at all.

You see, the music I felt was “born” in me was the music I had heard in Yonaguni. Grandpa, the marlin, the people of Kubera, that was the song that resounded there. I can still hear that song at night. If my relationship with Yona becomes longer, surely we will be able to sing it too. But for now, I can only listen. I hadn’t even thought about turning their songs into music for the film until now.

So, I had to find a way for me to sing it. I tried to convey the songs that I had unquestionably heard with my own ears but had never given as a gift to people like Masahiko Satoh and Hiroshi Sakata.

Sakata was just like me; he already turned their songs into sunlight. I thought I could force him to sing it spontaneously (laughs).

And then, I started speaking in front of the musicians.

“I have seen Yona.”

“I have met Grandpa.”

“I have talked to the people of Kubera.”

After that, I talked about the sea, the sky, the wind, the festivals, the fish, the children, and I shouted with all my heart, “Please make the music.”

And that’s how that music was created.

– Interview excerpt, from original liner notes.