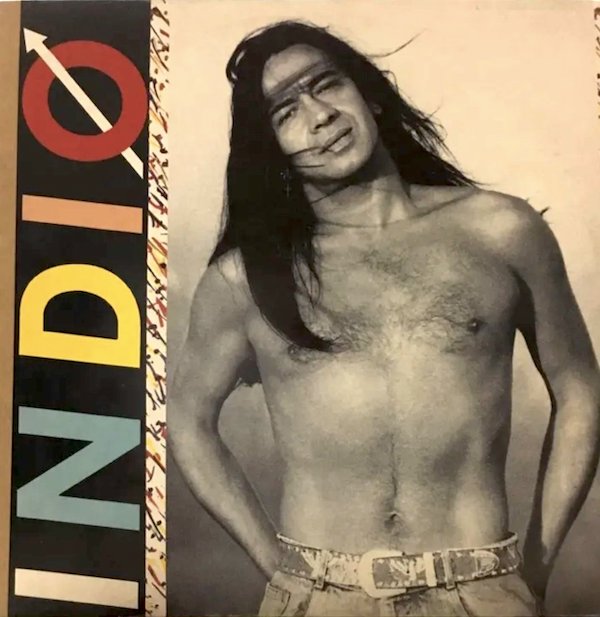

Simply wonderful summer moods abound in this one. What’s the one I’m referencing? None other than Fernando Girão’s Índio, an intriguing release combining deep Brazilian ethnic and indigenous folk music with new wave, experimental electronics. It’s as Fernando hinted at in the name of his record label, fusion etnica or ethnic fusion. Many moons later it does what I love about records much like this one: point to an accessible form of “immigrant music”, one that blurs the borders of style (and nationality) it traverses.

If you would ask Fernando how he came up with this sound, I’d wager, he’d point to his life outside of Brazil for preparing him to think outside established strictures. Although born and raised in São Paulo, various life turns found him forging his life elsewhere. Fernando had tried to balance a professional career that offered him the opportunity to be a star futbol player or to follow in the path of his parents, both noted fado musicians who had introduced Brazil to the style.

Fernando, for reasons clearer to him than others, felt that his greatest contribution to others should be through music. As various pro soccer tours in/around Brazil yielded to larger opportunities in Portugal, Spain, and elsewhere, in Europe, so too did his floundering love of music expand as he took in all the music censored from his homeland. Eventually, as he journeyed away from Brazil to Portugal, in the early ‘70s, he left his footballing career behind and start or join groups like Portuguese prog pioneers Pentágono, or collaborate with artists like Branco De Oliveira and Saga, shifting his earlier roots in Brazilian soul and folk music into virgin territory touched by jazz and “world music”.

For three years, various opportunities opened up in Africa and he’d settle down in Angola with a different group, Heavy Band, that afforded Fernando time to expose himself to a different culture. So, for that span of time, he’d live and flower creatively/personally, in the continent, developing a taste for the music and a responsibility to understand those people that felt “alien” before.

However, as soon as Fernando began to exploit the small artistic openings provided by the Portuguese authoritarian government at the time, things came crashing down. What was once an equally lucrative soccer career fell by the wayside. His work with Jorge Palma, a Portuguese protest song dubbed “Pecado Capital” they tried to release as a Eurovision entry got them in the wrong way with Portugal’s then, corporate fascist leadership. By the mid ‘70s, Fernando was apprehended by PIDE (Portugal’s State Police) and placed in jail, in effect, knee-capping his early rock-influenced career.

When Fernando was released from Portuguese prison, he took a different turn, writing under the nom de plume “Very Nice” showing an extensive sphere of influence he’d rather explore. What felt like a light, Zappa-esque, experiment would yield a more accomplished vision just four years later when his first album debuted under his name, 1982’s Contos Da Europa Tropical. In that release, moody quasi-tropical soul ballads like “Joana (Do Vão Da Escada)” gave us a taste of the torching vocals once meandering aimlessly elsewhere. On songs like “Intelectual De Café” fusion-style arrangements from new school MPB musicians allowed him to further his own attempts to tie-down the kind of “soul” music he wanted to make.

1983’s Africana was the turning point, in a big way. On it, together with brilliant Salade De Frutas keyboardist, Quico Serrano, they began to explore Fernando’s own stylistic makeup. A sprawling visionary thing, where the “European” New Wave, technodelic, palette could find a way to fit Fernando’s love of African music and his own Brazilian background, touching lightly on his indigenous roots left behind on earlier work. Stellar tunes like the title track, “Divorcio”, and “Amor De Ministerio”, showed that for this crew, the keys to such fusion laid not in the chin-scratching music of his past but in the grooves found in the dancefloor, with music that could clearly and accessibly treat his listeners to what was Fernando’s truest muse.

Five years later in Spain, after years of building up a vast repertoire contributing music for TV dramas, ballets, and other scenes, Fernando took it upon to dig deep into his well of musical knowledge and create another album (one more personally tied to the country he certainly felt at times far more estranged from). Índio, as hinted at in the opening track, “Índio Não É Só Quem Vive Na Floresta”, tries to capture this idea or an idea of indigenous culture not being lived out in the jungles or forest but living in our “modern” world.

Themes touching on man’s interaction with ecology, of our connections (or lack thereof) with other cultures, are also huge meditations captured in fantastically vivid and blunt songs like “Porque É O Homem Tão Burro?” and “E A Vida É Tão Ilógica”. The ethno-tropical-electro explored in Madrid with various grooveboxes and synths yielded to revelatory quasi-spectral art soul that’s neither Brazilian or of any other nation’s creation — songs like “Palavra De Índio” and “Viagem Pelo Rio Amazonas” evoke the ambiance of an ecology that’s much closer to his heart than any lineage found on a physical plane.

The call and response of Africa transported itself to a parallel journey (heard in the sonic techniques of the Caribbean and hypnotic phrasing of Fernando’s mestiço-tinted arrangements) where Fernando’s powerful voice held a justly, certain attraction. And, somehow, Gal Costa’s influential Índia, finally, found another worthy follower to promote those not fearing their mestizaje.

Personally, I go back to those otherworldly songs like “Deixem O Índio Viver” and “Coração” a bonus track from the same sessions, shared on some long out of print CD where Miguel Braga joins in to help Fernando create an atmosphere that just feels reverential. Demanding your attention, tracks like those anchor the album. Anchor to what, you may ask? To some communion, any native feels with another, existing on the same plane we all have to live in. You might not know all the words to place those memories, places, and people, but there’s just something about music to power you through the translation — all things worth living for and with.