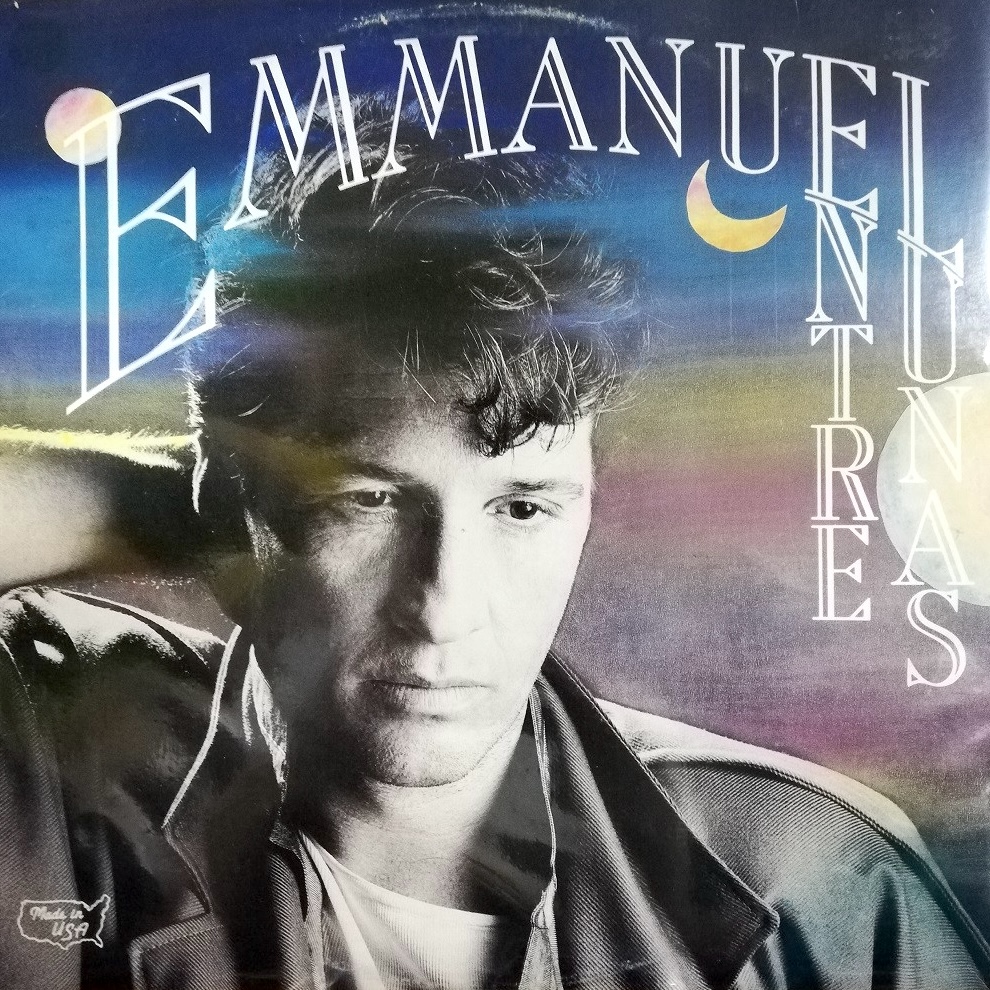

As the child of first-generation immigrants, I imagine, many of y’all have had a similar relationship with your parents’ culture as I’ve had with mine. It’s that of initially looking at anything that came out of it – its music, its film or television, its arts or cuisine – with suspicion and (worse) seeing it as lesser to the one we’d like to assimilate into. Insert [x] band or artist, whatever your mom or dad had on TV or played on the radio, it doesn’t matter whoever they were, they obviously can’t measure up to anything in American pop culture. It’s this kind of closed-mindedness that, in hindsight, has forced me to work twice as hard to rediscover a lot of what I ended up missing. It’s what compelled me to share Emmanuel’s Entre Lunas.

As a young child, one of my fondest memories was tucking down, after a long day trailing my parents around shopping, spending Saturday evenings with my family watching Univision’s long-running variety show, Sábado Gigante, on our tiny color TV. Running for nearly three hours, In between all sorts of classic variety show troupes – from game shows and slightly racy reveals – it was through that show that I was able to experience a veritable parade of the who’s who of Latin American pop culture. From the dulcet tones of Venezuelan balladeer José Luis Rodríguez (aka El Puma) to Mexican pop groups like Timbiriche or salsa artists like Marc Anthony, it appeared that there wasn’t a single act that escaped its host’s, Don Francisco, stage and couch.

It was in shows like Sábado Gigante and airings of Chile’s Viña del Mar song festival that I remember first encountering my first taste of Latin culture. It was through these early personal cultural touch points that I remember first encountering Emmanuel’s music.

If you were a Mexican-American child of the ‘80s you would be hard-pressed to avoid balladeer, Emmanuel. Everywhere you turned your dial to, either on Spanish-language radio or Spanish-language TV, it seemed like his hit song, “Toda La Vida” was playing somewhere. To me, back then, on stage he seemed a bit “alien” to any of the prevailing scenes I understood. In the way he sang, he did it in a different, sophisticated way – much like the Europeans, I thought. He performed and dressed with a certain verb – much like the Spanish or South Americans, I imagined. Yet, upon learning the truth, the truth that he was of Mexican descent (just like me) I felt, in some stupid way, disappointed. I felt: Why was he trying to act like someone he isn’t? It’s my lack of pride in my culture that spurred me to cross him out.

Back then, little did I know that Emmanuel was already nine albums deep in a long career. Before I was born, Emmanuel had already made this journey to stardom and to this stage eight years prior. It was back in 1980 that Jesús Emmanuel Arturo Acha Martínez had arrived in Chile to try to make a name for himself as a balladeer through one of his earliest Mexican radio hits, “Tengo Mucho Que Aprender De Ti”. Appearing on the original pre-Univision version of Sábado Gigante, in a way, Emmanuel was making the attempt to expand his audience far from his homeland. Six or seven albums later, and nearly a decade afterward, it was that constant push to expand and push his audience that would make him a star selling out venues like Mexico City’s Plaza de Toros or New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

It would take time before I’d discover that the first hit I knew of Emmanuel had once been a hit elsewhere, in Italy, by its original creator, Lucio Dalla. Knowing what I know now, now I could understand how his career had evolved and how he might not have been the artist I pegged him for.

There was a time in the early ‘70s when my namesake, Jesús Emmanuel Arturo Acha Martínez, turned out to be a different person. Born in 1955, in Mexico City, to an Argentine bullfighter and a Spanish-born singer, Emmanuel’s parents hoped that their son would follow a different career than they took. However, like his father, Emmanuel couldn’t avoid following in his footsteps. For four years, as soon as Emmanuel could pursue a life in the bull ring, he’d do so. “Performing” as a torero in Mexico, Spain, Peru and elsewhere, it seemed (at least in the early ‘70s) that Emmanuel was quickly making a name for himself in the bullfighting circuit.

It would take a near death experience, a goring in the ring, that would set him on what would be his path into music. Severely injured while bullfighting led Emmanuel to rethink his chosen career path. Should he go back to become a chemical engineer like his family wanted? What else could he do? Finding himself suffering through bouts of deep depression and resigning himself to saying goodbye to the torero life, Emmanuel found solace in music, poured himself into this artform, writing his first songs and singing his first ballads. In short notice, this torero-turned-cancionero found a second lease on life through music, signing to RCA Record’s in Mexico.

For nearly a decade, through the aforementioned hits and albums like the multi-million unit moving Íntimamente…, Tú Y Yo…, Emmanuel, and all the way to 1986’s Desnudo, Emmanuel worked his way to becoming a household name in all of Latin America, becoming the de facto titular head of the new generation of balladeers. And in keeping with an ever-restless personal push to expand his boundaries, Emmanuel began to push those external boundaries that had increasingly felt like they had been fencing him in.

In 1987, Emmanuel began toying with the idea of singing in English. It was in the music of artists like Bryan Ferry or Peter Gabriel, New Wave, or artists in the vanguard of pop music like Michael Jackson and American urban soul scene, that Emmanuel felt his prior music was supposed to be judged against. There he felt his music was coming up short. As much as Emmanuel had arrived to a certain echelon of pop notoriety, critically, he felt he had to shake something up and push himself and his audience ( most importantly) in a new direction. As an artist he owed himself an album that spoke to him.

While working in various recording studios, Emmanuel had taken a liking to the newfound sonic gadgetry of the time. From samplers to synths and drum machines, all sorts of intriguing new tools seemed to present some kind of answer into the sonic direction he’d like to take. Inspired by Lucio Dalla’s music, one that found a way to evolve the Italian balladeering tradition into a contemporary world, Emmanuel reached out to Lucio’s longtime creative partner, Mauro Malavasi, his producer and arranger, and proposed a collaboration. Mauro would accept and invite him to record the majority of this record in between his home studio Bologna, Italy and in pro-level studios scattered in California and Florida.

For what would become Entre Lunas, Emmanuel began to conceive this idea of the romantico moderno or “modern romantic”. In America, Emmanuel had various opportunities to see how his audience and other audiences had responded to singers. Names like Julio Iglesias made their money to Anglo audiences by leaning in heavily on the “Latin lover” stereotype. Emmanuel understood that he never felt that type. For him, the machismo and chauvinism of the past felt anathema to how he personally felt about women and his relationship with them.

For Emmanuel, performances by artists like Tina Turner – then in her Private Dancer peak – felt transcendent. In Europe, similarly, where he was less known, he could take in concerts where balladeers like Miguel Bosé (to name precious few) exposed a certain emotional feeling without resorting to histrionics or affectations. This idea of creating music for romantico modernos would end up experimenting with being more of himself – shucking off a lot of useless tradition, exchanging it for sophistication (in music and writing). Entre Lunas would be his most ambitious work yet, going deep into turning away from that decadent ‘80s lifestyle and into one of hope and renewal where his Latin identity holds worth in a world that devalues it.

Looking back, I’m still surprised how few remember Emmanuel’s wonderfully ambitious album. On songs like “Una Vieja Cancion” the production ghosts of Phil Collins “In The Air Tonight” and the Blue Nile reappear, conjuring new balladeering shapes and figures. Even its most dated track, opener, “Grito De Dos” finds something interesting to fuse from influences mined in England’s post-punk scene.

Where Entre Luna is worth its weight in gold is on tracks like “¿Que Será?”. On this gorgeous bit of sophisti-pop one gets to luxuriate in the absolutely magnetic, mercurial, silvery vocalese that Emmanuel’s singing had evolved to. In a time full of lesser-than, Avalon-style castoffs, from Mexico came an unlikely Icarus flying above such rarefied airs.

You hear this idea of romantico moderno start to take its full shape on a track like “Esos Ojos”. Written by Luca Carboni, Emmanuel’s Balearic interpretation of this Italian ballad walks that fine tight-rope between latter-day Leonard Cohen and the slightly-hidden dreamy pop of its original songwriter. It’s a song like this one you can palpably feel the freedom given to fellow musicians like Lucio (who’d guest on keyboards here) or KC Porter and Mark Spiro who’d contributed before but were able to push more of the stylistic ideas they had before. And somehow on this record Emmanuel’s latest reimagining of a Lucio Dalla song, “La Última Luna”, spirits something more forward-thinking than the hit of his past.

There are mutations of Spanish europop found in tracks like “Y La Lluvia Entró” that bring it more in the league of new school soul music. Impressive motorik-style love songs like “En La Noche” simply have no background in Emmanuel’s history. It’s what makes one wonder how his audience reacted to such a record. After its release, huge critical success would find this album, Entre Lunas, slot into the inaugural “Lo Nuestro Awards” – precursors to the Latin Grammys – as an entry in its pop album of the year category in between releases by artists like José José and the aforementioned, El Puma and albums like Isabel Pantoja’s Desde Andalucia (its eventual winner).

Looking back, it’s like seeing Bowie’s Heroes tucked in between Stevie’s Songs in the Key Of Life and Boz Scagg’s Silk Degrees. In the arc of what stands the test of time, such an album was an anomaly few would understand then (even if they understood the artistic risk). Finally, Emmanuel caught a wave that deserved a different category to be judged on.

I’d live on to miss Emmanuel’s eventual rocket to Latin stardom, one that would take him to meet the King of Pop after a concert. It was backstage where Michael would share with Emmanuel feeling wowed by his stage presence and music. It’s that feeling Emmanuel once felt watching Tina on stage. In the end, it seems that his old and new fans understood his change in direction and rewarded him appropriately (to their credit).

I’d live on to miss his evolution into New Jack Swing and becoming as close a Spanish-language answer to George Michael as we’d ever get…until he’d land on where he is now, succumbing to his Sting-indebted stylistic cues, leading him down the wrong side of adult contemporary. Yet, here I am coming back to the fold, rediscovering this wonderful bit of freedom, one I feel is ready for others to rediscover, one that reimagines that old-fashioned love song in a way that still feels surprisingly forward-thinking.