Out of all the things I remember about my time in Japan, funny enough, one thing I can’t seem to forget is this: just how “French” so many things are. Walking down the street, shopping around, looking for a bite to eat (or just a place to relax), more often than not, you’re bound to run into a boulangerie, a patisserie, or a boutique, a place or a shop, whose owner and patrons have fallen under the spell of that Old World power. I kept asking myself: “Why?” When so much of the world has moved on from French culture, why has Japan remained so tied to it? Surely, that answer must explain the staying power of albums like Clémentine’s Long Courrier.

Looking far back, it’s not difficult to ascertain that the connection between Japan and France began in one direction. In the late 1600s, when France was in thrall of all things “Oriental”, as cafe society grew out of Turkish influences, and those in coffee-shops kept looking further east for ever more exclusive ways to separate themselves from the rest of high society, as trade routes increasingly grew, Indian textiles and Chinese porcelain, became less valued as a luxury good. When Orientalism reached the shores of Japan, French upper crust consumers found their most exclusionary market. For those that could afford it, the amount of Japanese fabric and lacquerware in your possession, became the sign of your status.

This early Japonisme would truly come into its own nearly 200 years later as Japanese goods, goods which were once almost entirely impossible to buy in Japan’s Edo period, became easier to procure and be given a much wider birth to it in French (and to a lesser extent, European) culture. If you could afford to buy it, you too could be inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints, Meiji-era garments, and a vast array of new Japanese decorations.

So, to cut a long story short, when French artists began to turn the mirror around and create art and gardens inspired by Japanese motifs, as Japanese culture itself opened itself to Western ideas and global trade, Japan itself saw validation in French culture as something to aspire to. If as a Japanese person you wanted a template to follow of what “high culture” was, France was a great start.

If you go back to the ‘60s, it was France’s yé-yé music that gave, a largely, young Japanese feminine audience an outlet to explore pop music and style that fit a less aggressive form and sensibility. While in America names like France Gall, Jane Birkin (R.I.P.), and others made nary a blip in culture, in Japan such names lived on way past their heyday, influencing fashion and affectations, in such a way that certain aspects ingrained themselves as part of the larger contemporary Japanese culture.

Add to that visual mix, the aesthetics of French New Wave which shared a lot of the minimalism and existentialism present in Japanese design. Then finish it off with the shared vocabulary phrasing and attention to detail, and you could imagine the stew of culture was made for cross-cultural dialogue. Whole schools teaching French experienced a boom in Japan, while that language keeps dying off everywhere else.

Fast forward a few decades, find yourself in ‘80s Japanese society. Center yourself around a country where its workforce is enjoying the peak of its economic power. It was during that time when Sony Music – as a way to cater to a vast media market starving for music to show off this new sense of wealth and status – looked at French music as a great starting point to hit that demographic. Looking at their catalog and roster, Sony reached out to Victor Mintz, founder of French contemporary jazz label Orange Blue, and signed his daughter, Clémentine, as a new chanteuse that could take both France and Japan by storm.

Looking back, Clémentine Mintz wouldn’t appear to be the first person I would imagine to be one of the most known French singers in Japan. クレモンティーヌ, as she is known in Japan, was hardly a presence in her own native land. Although born in Paris, Clémentine spent more time outside of it (whether in Brazil or Mexico). When Clémentine came to be in France, her musical roots had developed more from the world of bossa nova and jazz. Following her dad around the world, had allowed Clémentine to think of herself as more as a global citizen than entirely “French”. After a chance meeting with Ben Sidran in Barcelona, her first record with him, 1988’s Continent Bleu explore more of a certain strain of classic urbane vocal jazz in America than anything in her country. Yet, Japan is where Clémentine would find her voice.

One could argue that Clémentine would find her footing in Japan, because she stepped her feet in Japan to do so. Brilliant early records like Spread Your Wings And Fly Now!! and Mes Nuits, Mes Jours – not to say the least of her debut Continent Bleu – made the long journey to Japan, where translated into Katakana, were hugely successful, breathing new life to classic mood music backgrounding intimate Japanese soirees. However, in 1992, at the urging of Sony, she was invited to Japan to record her first full record in the country and give it a go with a career there.

Preternaturally shy, Clémentine traveled with her father and family, left to figure it out in the studio with the Japanese musicians she was assigned to work with (as her father went out jazz record shopping). Thankfully, for Clémentine, the musicians she would collaborate with would be simpatico musicians like the duo of Gontiti and a slew of characters from the Shibuya-kei scene like Keitaro Takanami from the Pizzicato Five or Kenji Ozawa who understood her sensibility and kindly worked with her, being careful not to take over the recordings.

That masterful first Japanese-made album, 1992’s En Privé (Vol #270 Pour Tokyo), displayed some Alice Through The Looking Glass vibrations. On a record, largely painted by Japanese musicians, a certain French sensibility (almost entirely not there on her own recordings) appeared in its own sophisticated form, with confident songs like “L’été” and “Tu Ne Dis Jamais” showing that her adopted fanbase could swing just like her. Others like their cover of “Pillow Talk” and the funky “Dans La Rue” showed that there were other angles such nouvelle chanson could take.

En Privé (Vol #270 Pour Tokyo) proved, artistically, at least for Clémentine and others, that if you try hard enough, standing in front of Tokyo Tower in the springtime, you can find a new fresh French aesthetic in the most far flung places. Touring the album in Japan, to great success, she realized the connection they had with this music. What was once a one-sided love, was now flowing both directions. It’s that idea: that in Japan she could find a fresh take on her own music, that would drive, arguably, her next recording.

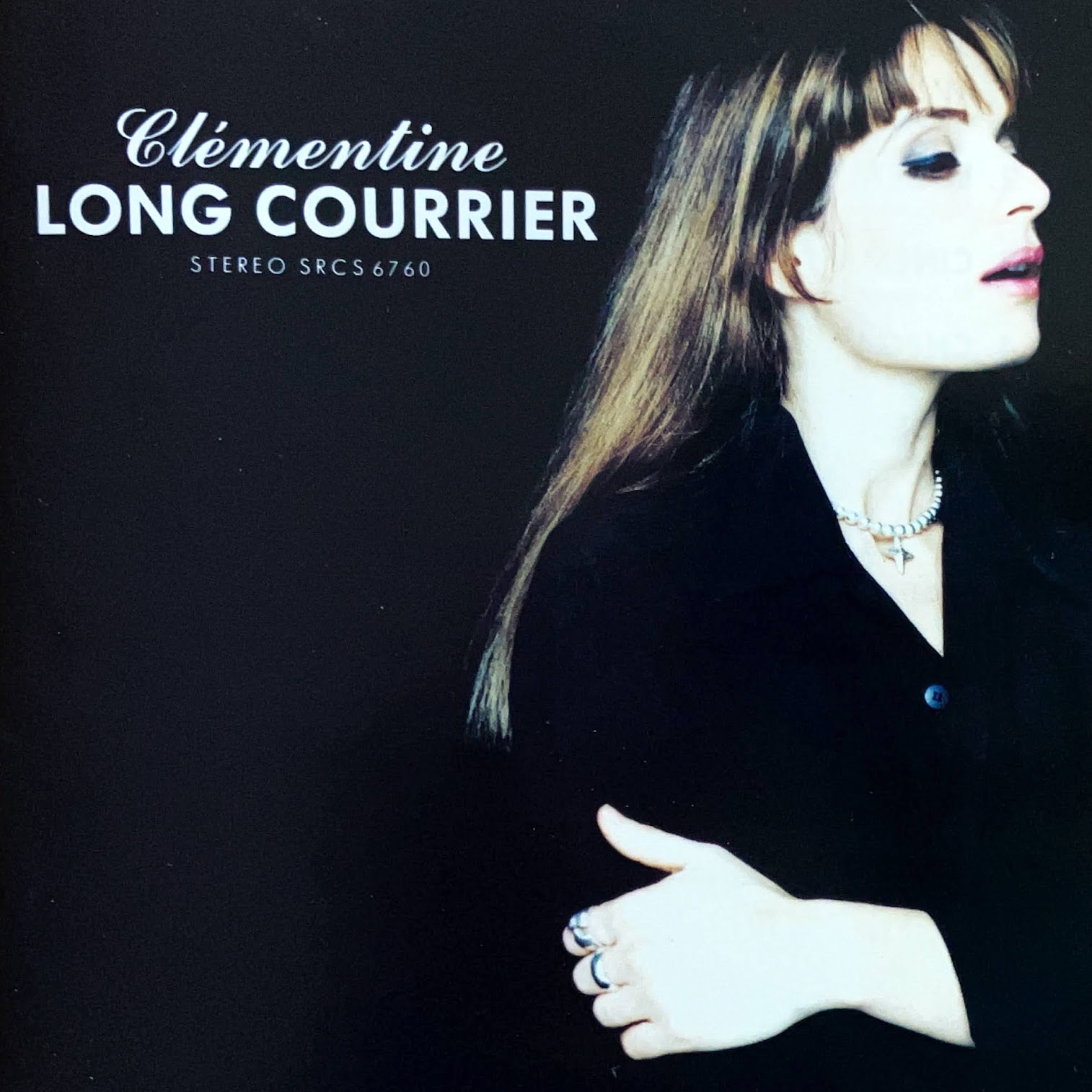

The appropriately titled Long Courrier, was recorded over the span of two years. Although she would record a few covers, largely, the bulk of this record would be turned over to new Japanese lights guiding their music to newer places.

Under the auspices of rare groove producer Yasushi Ide of King Cobra, sessions began in Harajuku in October 1992, then picked up in March and April of 1993. In some sense, those seasons (so special in Japan), transmitted themselves to the music that had a certain new maturity and experimentation than anything she’d done before.

The evolution of pop was something present in Long Courrier. Opening track, a remake of Stevie Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour” predicted or recemented that European electro-pop sound we’d hear in bands like Air or Stereolab. The special tracks were songs like “Le Beau Félix”, original tunes that went further into newforms of jazz music, in the realm of sample-heavy deep house and dubby trip-hop with production from artists like Manabu Nagayama that spoke to Japan’s own atmospheric dance scene. Songs like “Cinéma Muet” were playful originals that touched closer to Clémentine’s ties to latin music and the classic pop song.

For every hat-tipped song like “Chega de Samba” that aspired to move away from lounge exotica, there were genuinely astounding tracks like the dancefloor burner, “Indécision”. On songs like “Indécision” co-written by ambient house producer Yukihiro Fukutomi, one can hear that Clémentine could venture to more forward-thinking territory and not lose that certain haze in her music. Their more uptempo collaboration on this album, “Glamour Girl”, proved that if chanteuses were given space, they could unfurl on any track.

What’s fascinating about Long Courrier is that it has all these surprises and twists that should have been in Clémentine’s music. Long-form tracks like “Fille De La Mer” by King Cobra aspire to that spiritual form of jazz she had touched on (on her earlier Coltrane covers). This was mood music but in different shades of blue. You hear that in the gorgeous acid jazz sashay of Clémentine’s and Shinichi Osawa’s (of Mondo Grosso), “Happy Hour 6 To 8 PM”.

As much as Clémentine could have looked back, she owed it to her Japanese audience to look forward. In some weird way, this genuine simbiosis, of a French artist more known in Japan working with Japanese artists more known for their love of things outside of Japan (and in France), came together to create something that pointed upwards to some new fascinating dimension. And if you squint hard enough, it does give you a semblance of an answer (or at least the feeling) one gets encountering the French experience in Japan.