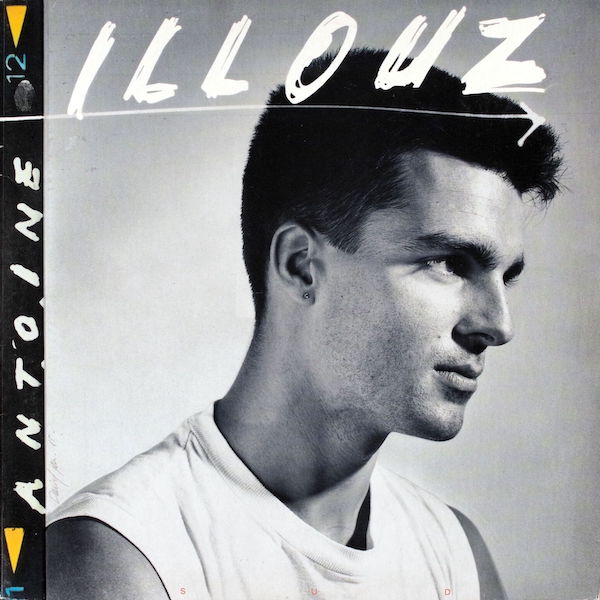

Jazz. Why even bother? At least, that’s what I ask myself when I choose to share something from that realm. Of all musical rorschach tests, it is Jazz, I feel, that seems to feature prominently as the one. Does one highlight its technical proficiency (and thereby, turn off a large part of the readership)? Does one go toe to toe with the emotional resonances behind a certain release (thereby capturing the stereotype of the awfully pretentious jazz buff)? You could say, the struggle is real, because I really want to speak about French trumpeter Antoine Illouz’s wonderful Sud without waxing poetically about it. Its music – first and foremost – that anyone can instantly understand without a vocabulary lesson behind it.

It’s not for lack of trying that very little info exists about today’s artist. Piecing together what I can, I see that Antoine was born in Paris, in 1959, to notable Franco-American contemporary music composer Betsy Jolas and a father of Algerian descent. It appears his parent’s global, cosmopolitan, livelihood afforded him the opportunity to imbibe in worldly creative influences. By the time he was a young adult, Antoine had become proficient in his core musical studies to go from the CNSMD de Paris (aka the Conversatory of Paris) to transferring over to America’s Berklee College of Music to escape the stiffness of “classical” teaching.

In America, Antoine was able to fully explore newfound styles germinating in culture. Whether it was the burgeoning no wave movement or the rise of “world music”, seeds of different ideas were being planted into what he’d want to create on his own. In France, he’d work with such outer-edge groups like Super Freego, the Ornicar Big Band, Big Band Lumière, to name a few, and backup huge African artists like Manu Dibango and Salif Keita.

It was this buildup of musical vocabulary that would express itself perfectly in Antoine Illouz’s debut. Seemingly under the influence of Jack Johnson-era Miles Davis and striking a pugilistic tone, willing to push his chosen quintet to strike cleaner, leaner, and spacier moods, Sud positively brims with ideas that hint at a sort of “fourth stream” music. It’s mixing that early modal-style of jazz vamping with the hypnotic, harmonic music from Asia and Africa.

What can one say about Antoine’s trumpet tone? As heard in the opening track, “Jerry et Motobe Fils de Khan”, Antoine’s muted tone effortlessly weaves in and out of any maelstrom, like a boxer, working the corners, locking in his band to certain grooves and certain expressions.

Recorded in Paris, in the waning days of summer (Aug. 26, 27, and 29), Sud seems to oscillate between fiery, longform fusion and heady, quietly, moving modal movements in a way that sounds undated. It’s gorgeous moods that inform tracks like “Naïf” and “Nocturne” to take affecting leitmotifs and run them through the gamut of dynamic shifts.

In Sud, exploratory lyricism by guitarist Louis Winsberg takes a beat and explodes into pointed squall. The plaintive meter of drummer François Laize and bassist Jean Bardy maintains a spatial counterpoint. Keyboardist Jean-Pierre Como’s always poignant atmospheric tones appear when these songs necessitate it. On every track, Antoine, once again, parries in those shots of elegant trumpet phrasing to knock you out.

Brilliant albums like 1988’s equally brilliant Wait! and 1991’s nomadic Mogadiscio would follow Sud. However, I think there’s just something about his debut that signaled a new voice in Jazz that still remains fully undiscovered. And like the best jazz, it’s immediate and multi-layered, commanding itself (simply) by existing in a quick moment.