Sometimes the hardest thing isn’t putting words on screen. Sometimes the hardest part is finding space to write about a certain piece of music you’re not completely certain others will understand (or have the patience for). Unfortunately, you know me, and you know I have patience to spare and more than enough time to choose to reflect on something. And today, that something is an album by Qigong master, Liu Jincheng, appropriately titled: 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)).

I’ll cut to the chase and let you know that 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)) isn’t made for everyone. It wasn’t made for today’s track-based, click around to find a track you like. Although released in Japan, in 1991, on the CD format, 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)) consists solely of one track: “中国氣功音楽 (Chinese Qigong Music)”. It takes time to appreciate what it does.

It’s that “中国氣功音楽” or Chinese Qigong Music that will quite possibly clear the stage for many of you. Much like the practice of that martial art, if you simply skip around the album you’ll most likely miss why it’s worthy of your time. If you can, clear up or make a bit of space to hear all forty-six minutes of it. What you’ll hear on 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)) is Liu Jincheng putting to practice what the qigong artform aspires to, into music.

Liu Jincheng was born in Changchun, China in 1948 raised in that generation that would have to live through the vast majority of Maoist Communist China. Thankfully, for Liu, since the age of 10, he fell under the tutelage of some pretty intense qigong practitioners and learned the practice while studying other traditional Chinese medical theories. By his teens, Liu would expand further his studies, learning yangqin (a Chinese hammered dulcimer) under renowned performers of it and found a liking to music, enough so to major in “ethnic music” theory at the Shenyang Normal University.

It was in the early ‘80s that Liu would move to Japan and found one of the earliest “song and dance” troupes that introduced the links between Japanese and Chinese music, in Tokyo. It was in Tokyo, where Liu would enroll in the Tokyo College of Music, studying percussion and composition, deepening his understanding and knowledge of traditional Japanese music. By the mid ‘80s, Liu would open up and teach in one of the first qigong studios in Japan, obtaining a license to practice music therapy.

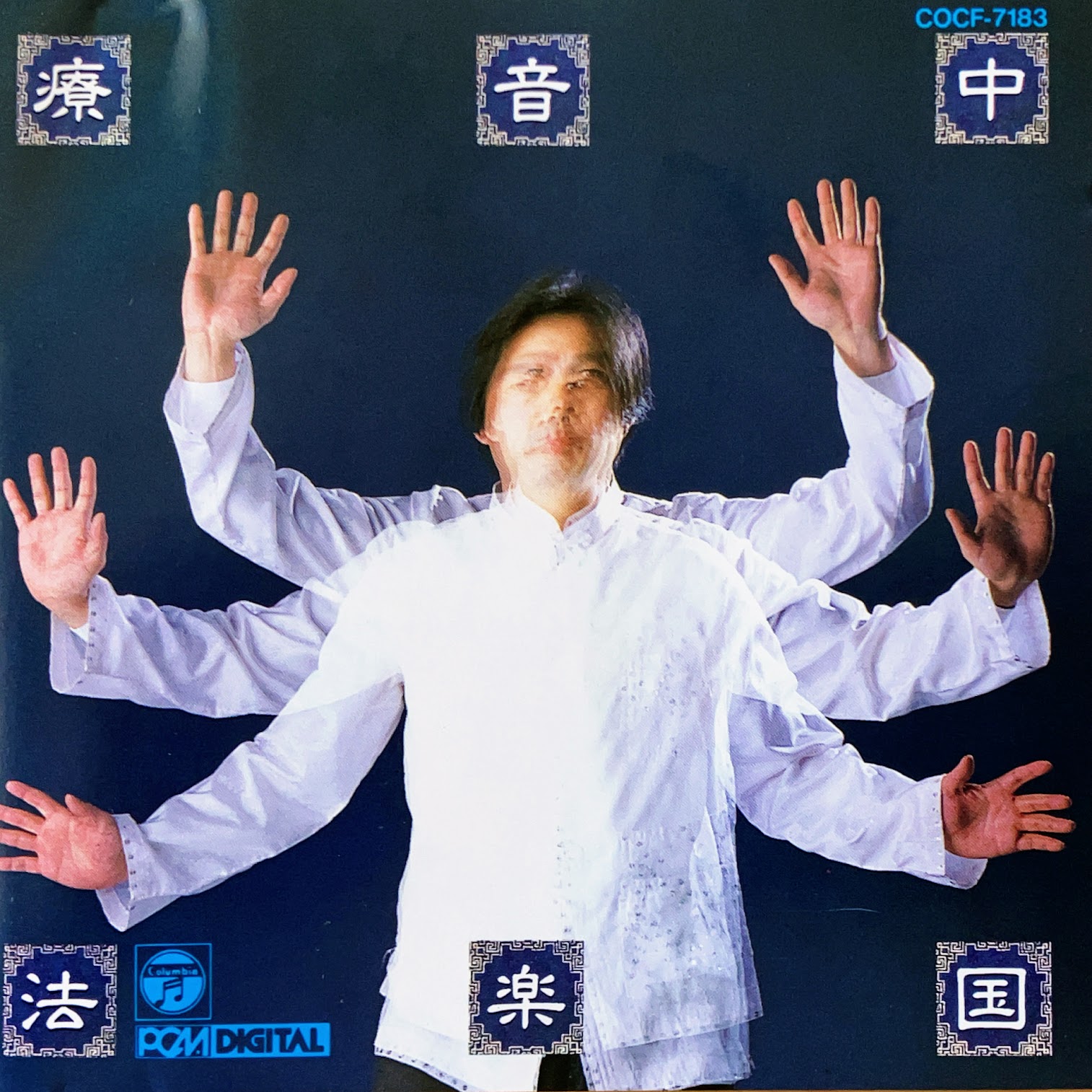

Through programs on Japanese TV, viewers of NHK or Nippon TV, could find Liu leading them through exercises meant to relax the body and center their focus. With time, Liu became the leader of the Tokyo Chinese Qigong Association and founder/director of the Musashino Therapeutic Institute. What all this was building up to, of course, was his attempt to use multimedia to bring the ideas and the many limbs of qigong into a modern context that contemporary audiences could absorb.

In 1990 or 1991, Liu would sign with the Japanese-based Columbia record company to introduce a new angle on music therapy – one marked on qigong principles and motifs. To quote Liu, “Qigong music therapy mainly influences people’s emotions through the effects of rhythm (yang) and melody (yin).”

Working together with Chinese-Japanese erhuist, Yang Xing-Xin, Liu would compose this longform, nearly freeform, piece that aimed to, “harmonize the five emotions ‘anger, joy, worry, grief, fear’ according to the productive and destructive relationships of the five elements ‘wood, fire, earth, metal, water.’ By using traditional Chinese musical instruments like sheng, guan, di, qin, zheng, ruan, and pipa to play natural sounds like those of mountains, forests, valleys, bird songs, and insect chirps, people are guided into the beautiful natural environment.” The album sometimes quiets down to a breath, with all those involved heard as closely as they were recorded with microphones.

Hearing Liu’s wonderfully minimalist elastic album, one hears all those stochastic ideas cement themselves through forms that latch onto those different moods, each time those wonderful, age-old Chinese instruments performing illustrative melodies that do, in fact, hit directly (if not inertly) where they need to hit you. 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)) never sounds quite “traditional” as it should because Liu’s music tends to move away from tying itself too much to the past.

In the end, 中国音楽療法(一) (Chinese Music Therapy (1)) is improvisatory within a language built on a certain degree of order. I think, if you give it some space, before you know it those forty-six minutes you might have preciously held onto, will quiet, and disappear into the five-tone scale of ‘jiao, zhi, gong, shang, and yu’.

FIND/DOWNLOAD